Imagine you’re a 17th-century theatre goer of some means headed to Blackfriars Theater for a night of Romance and Spectacle with a little wry king-bashing and trap-door special fx. Imagine too, that the billing is something certified wonktastical complete with a magically conjured storm and a duke and his daughter with a villainous island native and possibly a few other goddesses and spirits and there is also a boatswain and a romance with the Prince of Naples*. For example.

Recreated Blackfriars Theater in Stanton, VA. I have been here, because I married a Shakespeare scholar.

Naturally, you may be skeptical. Of course, this playwright is known to be pretty amusing, but you keeping getting hung up on the boatswain. As you are taking a seat and procuring Ye Olde Concessions for your date, the ushers hand you a printed program titled THE ARGUMENT.

No really. THE ARGUMENT** prints, for your consideration, tonight’s plot, characters, goals, conflicts, and motivation; in fact, it tells you how the playwright and players expect you to feel when you watch the play. It’s a pitch, a query, a blurb, and back cover copy all-in-one.

It’s a contract—between you and the players, the playwright.

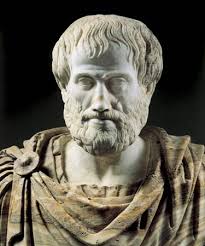

Now I’m going to crank back the time machine even further, so we can hang out with Aristotle. Aristotle really, really loved his buddy Sophocles’ plays. Artistotle would have retweeted the fuck out of Sophocles’ opening nights. Since this was not an option, Aristotle wrote Poetics, one of the biggest mash notes in history, where he claimed that everything he loved about Sophocles’ plays was what was required by any play to be awesome. Sophocles is most famous play is Oedipus Rex—a dad-killing, son-marries-mom, self-blinding wonkospectacular. Poetics requires that all stories have six elements: characters, a plot, a spectacle, beautiful language, a big idea, and singing/dancing***.

So, put your seat belt back on and we’ll head back to Blackfriars, where the curtain is about to go up on our desert island play. What you notice is that THE ARGUMENT, which you are now using to fan yourself because with all of these tallow candles and bodies it’s getting pretty dang hot, has a lot to say about those six elements. This is because 17th-century literati were deeply devoted to classical argument for what made art good, and applied a love letter from Aristotle to Sophocles to the entirety of the world of letters. In fact, we’ve never truly abandoned this devotion. Which makes sense because Aristotle’s Poetics is mainly reader response to Sophocles’ work, and I can’t imagine that basic human response to what makes something the goodness has changed, even in 2500 years.

So let’s put more banana peels in the flux capacitor and wander into a 4th Century BCE scroll store. Here, we’ll flip through Aristotle’s other work Rhetoric. This work applies to the three appeals of a successful argument: logos, pathos, and ethos. I want to lean against a marble column and talk about this in just a little bit more depth than the six elements of poetics (which we have a good handle on as interested readers and writers already), because this is where I begin to suggest a complex and useful craft tool for writing and responding to successful wonkomance. Namely, that a story can be epically, immensely wonked and be satisfying to an extremely wide audience of readers, possibly for hundreds of years, as long as it forwards a winning argument. ****

Logos demands that the author appeal to rhetorical reason through the use of enthymemes, which is a syllogism where the premises are not explicitly tested, but easily disputed—in other words, the author must build the argument on evidence that she links together with chains of meaning where one thesis follows another and they all support the major argument being made.

But really, what it means is that all wonkomance will call on Lieutenant Commander Data.

Data is a fully functional android, but until he got his emotion chip from Soong, he finds human behavior to be idiosyncratic and nearly meaningless. Data responds best to an appeal to reason where requests to him are based on demonstrable evidence. Data is a computer—he uses large strings of this evidence to create meaning.

Wonkomance may rely on poetics (any of the six elements) that are illogical, but if an element is inherently illogical, the wonkomance must have evidence throughout the story that argues for the meaning of that illogical element. An illogical plot, for example, could make for a wonkomance of the ages as long as overarching logos is satisfied by providing a chain of evidence for this plot. It will probably require that the other five elements support the plot—how the author characterizes the protagonists, for example, will argue that this h/h function best within the action of an illogical plot. Or the “big idea” of the story is revealed through the twisty caper of the wonked plot.

The author’s job is to win at logos. To look at all of her elements and shape them until they are a chain of beautiful evidence that appeal to the reader’s sense of reason. What’s sublime is that if the author looks at all the bits and pieces of her story as another way she can prove logos, all those bits and pieces can be absolutely wonked. The question the author asks herself, the question that every reader will have when considering logos is “does this story make meaning?”

Pathos is the appeal to the reader’s emotion. The author must win by either making the reader feel good about accepting the argument or feel bad about not accepting it, or possibly both.

Commander Deanna Troi helps us out here. Troi is an extra-sensory empath who has the ability to sense emotions, and because she is also a therapist, her intent to help those she is working with by identifying their emotions with them so that these emotions can be understood. I believe her power comes from her hair, but this is never explicitly stated in the show.

Like Troi, the author must identify the emotions in her story and argue for their acceptance by the reader. We’re talking about wonkomance, so we’re talking about love, and while it may be easy enough to identify love via simple h/h declaration, in fact, this is not enough. This love must be argued for. Not only do the h/h have to convince the other of their love, the h/h must convince the reader as well. Which means the author has to position herself as Troi, midwifing the emotional scenes from the action so that they can be specifically identified and claimed.

Again, this is particularly useful to wonkomance because readers and writers of a wonked love story are often most attracted to wonk via the pathos argument. We like to see an unusual appeal forwarded by the author—we want fucked up love. We also want to believe in this fucked up love. We want the author to convince us that this love is the only way, and we want every part of the story to argue, in chorus, for this love until we would rather gut ourselves than have it denied the h/h. In fact, the more fucked up the love, the more wonked, the more complex this argument really is. The more the author will have to examine every glance and conversation and sigh for how it supports this love. This is a difficult appeal to pull off—it’s easy for the reader to feel manipulated if the emotional action is not argued truthfully.

I saved Picard for last because, like always, Patrick Stewart brings everything in the entire world to full circle. In this case, his background is in the Royal Shakespeare Company, and he has played Prospero in our desert island play***** cited in our first time travel to Blackfriars. I know you totally thought I wasn’t going to head back to all that, but I am nothing if not tidy.

Captain Jean-Luc Picard is depicted as a highly intelligent and moral master of diplomacy and debate. He is truly the epitome****** of ethos, where the author must attempt to appeal to the reader by arguing that either a major element of the story, or the author herself, can be believed and trusted. This is where the author must “make it so,” where “it” is a trustworthy and believable wonkomance.

I feel that ethos, more than any of the other classical appeals, when it is not successfully argued for, may be the reason a reader DNFs a book. I DNF’ed a book recently****** that had the promise of excellent wonkomance but in sixty pages forwarded slut-shaming, inexplicable lack of condom use, and a hate-on for powerful working women. I could not believe in such irresponsible hater characters and I could not trust an author who created them. HOWEVER, ethos would suggest that the author may be able to still uphold ethos and present hateful characters and ideas if trust and believability were established in other ways—obviously this will be a difficult and complex argument for the author to make, but it’s not impossible. Poetics suggests a lot of elements for the author to consider; beautiful language, a tight plot, or some strong characterization (perhaps even a song and or dance) may save ethos in cases like this.

Leaving 4th Century BCE and returning to Blackfriars, we look again at THE ARGUMENT during intermission, in light of what we’ve learned. All of those elements are clearly vital to a good story. Aristotle knew it then, and we understand that now. We’re human, wonked or no, we want to see great characters in a terrific plot with big ideas and beautiful language (and possibly some dancing). But if we like our romance wonky, we have another burden as authors, and more requirements as readers.

There must be a convincing argument, and it must rest equally on three pillars—logos, pathos, and ethos. Just like Starship Enterprise could not manage without Picard, Data, and Troi, wonkomance, besides containing the expected elements of poetics, must be captained by a crew prepared for every contingency. In wonkomance, poetical elements are the necessary background for a foreground of argument in high relief. The more wonked your story, the more poetical elements are a priori, necessary, and the more difficult the argument for the author. The reader must not only be entertained, the reader must be convinced, appealed to satisfyingly.

The Tempest is 400-year-old wonkomance, and if its good enough for Patrick Stewart, than it’s good enough for everyone in the entire universe.

Footnotes:

*obvs The Tempest

**There are only about ten extant examples of playbill arguments in existence. For more information, marry a Shakespeare scholar.

***My challenge to you, romance novelists, is more singing and dancing

****Thesis-like area of this post

*****The Tempest

******I’m throwing out the Greek words all over the place.

*******No, I will not tell you what it is.

BONUS FOOTNOTE “It’s all Greek to Me” comes from Shakespeare: Julius Caesar

Well, from your clever juxtaposition of modern geek culture references, classical greek narrative theory and Shakespeare to make your wonkopoints, PLUS Patrick Stewart, I can only conclude that I must now stalk you online until you agree to be my internet wife.

Re: Troi: The hair, yes, but not the hair alone. It’s also the fact that she strongly resembles a luscious, human, chocolate fudge sundae. The woman is scrumptious like it’s a superpower.

Re: Ethos and DNFs – yes, yes, a thousand times yes! I think this is also behind that reaction whereby one not only DNFs that particular book but decides never to read that author again. When an author balances the characters’ flaws with strong writing in such a way that the reader trusts the author even if the characters appear to suck, that can be some of the most powerful writing out there. But if the characters suck and the author doesn’t make the reader feel that trust, it’s kind of like a hamhanded, unintentional fourth wall violation where the actor drops out of character. There’s that icky intrusiveness of the author’s/actor’s persona, that jerks the reader/spectator out of the world of the character. You just feel like you’re no longer in good hands once that happens.

I accept. You did propose, right? You must know a dork of my level would not require stalking to capitulate.

I’ve been insisting that rhetorical appeal must be applied to all writing, including fiction writing (and poetry writing, for ever, but it wasn’t until this most dramatic DNF over the weekend that more of the reader response piece intersected for me-particularly in regards to ethos. I think too, that there have been so many recent conversations in the community working to parse out if reader response is the only evidence for “good or bad” when what I think we want to talk about is this rhetorical appeal. In other words, rather than moving around the pieces of a work and breaking it down into its poetical elements when the piece shocks us or makes us uncomfortable or seems to break some rule, it may help to look at the work from the perspective of rhetoric.

I see a lot of reviews, for example, try to answer for ethos by looking at why a character in a work has produced an unsafe or triggering or maddening reader response, and all it takes in one person in comments to reply that they accepted the characterization of the character for the discussion to diffuse. While looking at what the author argued for in the story with rhetorical appeal may not provide answers, it is another filter or lens–just as any critical filter or lens.

And YES, rank disregard of ethos absolutely drags the author in, SO intrusively into the work. I would also argue that too much attention to ethos does the same thing–turns the work into what I’ve read others call an “issue” story.

It’s really interesting–these cross-hatches of reader response, critical filters, and argument. Helpful as craft, as well.

So glad I don’t have to resort to stalking. I really lack the requisite attention span. But you agreed, so we’re good to go, right? *geekfistbump* *totally miss each others’ fists and require a do-over*

Oh, and in my WIP I totally have singing, so there.

This is too fabulous! I really enjoyed the way you break it down into those three elements (And how did I never work it out that Data, Picard and Troi were analogs of Spock, Kirk, and McCoy until now? Though it is often argued that Kirk was more the perfect blend of logic and emotion, with a bonus of chesty manliness, but I like your ethos. And maybe Riker was the chesty manliness analog.) Anyway, being sometimes clueless this all is something I can really understand! Also, totally agree on the DNFs – and on the other side of the coin, it is SO nice to just trust an author. To have that feeling of being in good hands.

Also, this:

I so love!! In a way, it puts a puzzle piece in place for me on how these extreme romances operate, but really, all of them. Or why a hero like Zsadist works so well.

Spock, Kirk, and McCoy work as well for logos, ethos, and pathos, I believe, for different reasons. I chose my analogs based on the reboot of these tropes in the Next Generation, but also on my loins. :)

That trust is so easy to establish I think, too. Honestly, most authors, if my general reader response is positive and if they argue well for what they’re doing, I will devour their back catalog regardless of what any review or blurb has to say about the book (Carolyn, FYI, you are one of these authors for me). There are wildly uneven authors who manage to violate their umbrella ethos (and that’s what happened with the DNF book I cite), but this is rare.

It really makes the whole idea of “favorite author” so much more complex an idea, and why one person can have such an eclectic list. I think it’s also why readers may follow particular tropes–since many tropes in genre fiction are approached similarly (that’s why they’re tropes) it may be a way readers pursue ethos while trying new authors.

I don’t even have any words. I will be processing for such a long time. But thank you for the laughs and the argument (and THE ARGUMENT). Really great stuff.

This. “In fact, the more fucked up the love, the more wonked, the more complex this argument really is.”

So glad you took it on! Will be contemplating the three pillars of argument for some time …

What a lovely, thoughtful post. And no, I really did not think you were going to circle back to the theatre, but you did. I grabbed a quote to remark upon and then realized that Carolyn and, for one nearby at least, Serena, had already done so:

“We want the author to convince us that this love is the only way, and we want every part of the story to argue, in chorus, for this love until we would rather gut ourselves than have it denied the h/h.”

Just yes. Yes.

My gracious, I adore this post and perhaps also you, a total stranger. :)

How did I not know (remember?) that THE ARGUMENT was passed out before the play????? I was just discussing on twitter how satisfying all my bits of not especially useful information are to me. My day is now made.

As for the rest, there is so much here I want to think over, so many great points that ring true to me as a reader that I am going to have to reread this again later. I feel all super smarticle now too.

Pingback: On Voice | Wonk-o-Mance