I’m pleased to welcome Alexis Hall back with another guest post — this time one for the “Formative Wonk” files. I love this essay on reading and identity, and what we find when we’re young, seeking reflections of ourselves in literature.

———

It was pretty much decided I was queer from a young age, though queer wasn’t the word they used. It’s the word I use now because it’s the one that troubles me least, the one that evades definition, as I wish to do as much today as I did all those years ago. Back then I really had no idea what any of this meant, only that I was different in some way, not quite right, not quite what was wanted. In that world my queerness was as much my quietness, my cleverness, as it was any burgeoning sense I might have had about my sexuality. In that world, in the eyes of those around me, those things were inextricable. So I read. Looking for the mirror that would reflect my strangeness that I might begin to understand it.

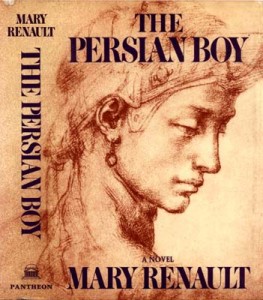

The first I found was Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, though I read it too young. I don’t know how it had come to be filed in the children’s library. I think, perhaps, someone had mistaken it for worthy, stodgy children’s history, which was why it nestled there in its dull brown cover between Rosemary Sutcliff and Roger Lancelyn Green, this bold, difficult, love story, narrated by Alexander the Great’s Persian eunuch, Bagoas, who a few lines of Plutarch suggest may have been his lover. It’s a fascinating book, a powerful and a poignant one, bluntly unapologetic in its depiction of homosexual love. To this day, The Persian Boy remains one my favourite books, reached for as instinctively as a partner’s hand in moments of distress or uncertainty. Now, I can see now Renault’s consummate skill, her effortless fusing of history and fiction, and the way she imbues such distant, inaccessible figures with the necessary emotional authenticity to make them real. How she shows us the pride of a eunuch, the strength of a courtesan, the person at the heart of a phenomenon, tenderness in war, and the peculiar seductiveness of Alexander’s conquest. It’s not a balanced love, perhaps not even a healthy one, for Bagoas’s devotion to Alexander’s greatness is not, and cannot be, reciprocal. But at the same time what they have, what they share, is undeniable. Powerful. Unquestioning and unquestioned.

The first I found was Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, though I read it too young. I don’t know how it had come to be filed in the children’s library. I think, perhaps, someone had mistaken it for worthy, stodgy children’s history, which was why it nestled there in its dull brown cover between Rosemary Sutcliff and Roger Lancelyn Green, this bold, difficult, love story, narrated by Alexander the Great’s Persian eunuch, Bagoas, who a few lines of Plutarch suggest may have been his lover. It’s a fascinating book, a powerful and a poignant one, bluntly unapologetic in its depiction of homosexual love. To this day, The Persian Boy remains one my favourite books, reached for as instinctively as a partner’s hand in moments of distress or uncertainty. Now, I can see now Renault’s consummate skill, her effortless fusing of history and fiction, and the way she imbues such distant, inaccessible figures with the necessary emotional authenticity to make them real. How she shows us the pride of a eunuch, the strength of a courtesan, the person at the heart of a phenomenon, tenderness in war, and the peculiar seductiveness of Alexander’s conquest. It’s not a balanced love, perhaps not even a healthy one, for Bagoas’s devotion to Alexander’s greatness is not, and cannot be, reciprocal. But at the same time what they have, what they share, is undeniable. Powerful. Unquestioning and unquestioned.

And when I first read it, I had no idea what was going on at all. I only knew that I was Bagoas’s age, that he suffered, and was ashamed, that he was different, in the way others perceived him and treated him, and that he survived. Bagoas is a difficult narrator, not always sympathetic, certainly far from reliable, driven to love Alexander initially as much by his own pride than anything you might call romantic: “And I said to myself, looking after him as he walked away, I will have him, if I die for it.” But I admired him so, for that pride, and I knew I wanted whatever it was he got. I had no notion what it was two men might do together, but it seemed like it was something worth having: “My body echoed like a harp-string after the note. The pleasure had been had piercing as the pain used to be before.” And, because my understanding was so limited, because these ideas seemed at once so abstract and so familiar, I didn’t think to wonder that one man might seek such things in another. Or that they could be found there.

And that was my first reflection: a Persian boy. I see him sometimes still.

The next came some years later. After The Persian Boy, I had found only misery, lovers doomed to betray each other or be torn apart by a world that could not accept them. Sometimes they murdered or raped each other, or got decapitated. I had just about come to the conclusion I would be more likely to find love as a Persian eunuch (I knew what this actually entailed by now, which will tell you just how unlikely my prospects of future happiness seemed to me right then) when I read Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man. Isherwood, I would later discover, was as frustrated as my younger self with what he termed the myth of the tragic homosexual, though on the surface his novel about a grieving, alienated middle aged gay man would seem to support, rather than contradict, this myth. Except, no. A Single Man is a book about life, not death, and grief is merely the mirror through which it shows us love. It’s a remarkably effective device – since Isherwood could not portray the reality of the love between two men, he depicts instead the reality of its loss. Just as a personal aside, this aspect of A Single Man resonates for me with The Persian Boy, or rather with a line from Funeral Games, the next novel in the series. Bagoas is only incidentally present in this book, but by far the most striking reference is this one, at Alexander’s funeral:

The next came some years later. After The Persian Boy, I had found only misery, lovers doomed to betray each other or be torn apart by a world that could not accept them. Sometimes they murdered or raped each other, or got decapitated. I had just about come to the conclusion I would be more likely to find love as a Persian eunuch (I knew what this actually entailed by now, which will tell you just how unlikely my prospects of future happiness seemed to me right then) when I read Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man. Isherwood, I would later discover, was as frustrated as my younger self with what he termed the myth of the tragic homosexual, though on the surface his novel about a grieving, alienated middle aged gay man would seem to support, rather than contradict, this myth. Except, no. A Single Man is a book about life, not death, and grief is merely the mirror through which it shows us love. It’s a remarkably effective device – since Isherwood could not portray the reality of the love between two men, he depicts instead the reality of its loss. Just as a personal aside, this aspect of A Single Man resonates for me with The Persian Boy, or rather with a line from Funeral Games, the next novel in the series. Bagoas is only incidentally present in this book, but by far the most striking reference is this one, at Alexander’s funeral:

[Ptolemy] had come remembering the elegant, epicene favourite; devoted certainly, he had not doubted that, but still, a frivolity, the plaything of two kings’ leisure. He had not foreseen this profound and private grief in its priestlike austerity.

That line never fails to move me. But, beyond the pain, there is a terrible sort of triumph, I think, at the heart of grief. To grieve is to love, to have loved, to love still. To live, and to be human, to be the same. The deepest cruelty of A Single Man is not that George has lost his lover, but that he is denied the space to grieve him. Like George himself, A Single Man is sometimes an angry book, a lonely and a bitter one, but it is also beautiful, hopeful and even celebratory. George is fifty eight when the novel opens; his partner, Jim, has been dead for about a year. These are not tragic homosexuals – they are people who have shared a lifetime, a banal, beautiful, perfectly recognisable lifetime, full of everyday, familiar, real love:

What is left out of the picture is Jim, lying opposite him at the other end of the couch, also reading; the two of them absorbed in their books yet so completely aware of each other’s presence.

The novel follows a single day in George’s life. He goes through his routines at home and at work, thinks of Jim, talks to his colleagues, teaches, meets up with a friend, embarks upon an anti-flirtation with one of his students, and it ends him with in bed, masturbating unrepentantly (and apparently quite satisfyingly) over the memory of two young tennis players he saw earlier in the day. Or rather it ends with the novelist asking us to suppose – he emphasises merely suppose – that George dies of a heart attack that very night as imminent demise is, of course, the only socially acceptable fate for the irredeemable homosexual. But this is little more than a piece of artifice. Because A Single Man is ultimately about love, the end of love, and the life that continues after.

So that was my second reflection: a grieving fifty eight year old. If he is my future, it is not so terrible.

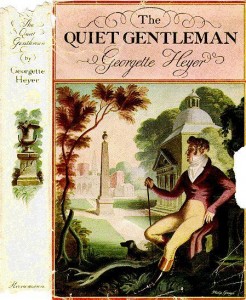

Then I found Georgette Heyer. But AJH, I hear you say, there’s nothing queer about Georgette Heyer. And maybe you’re right, but identification is more complicated, and more fluid, than the literalities of personal similarity. Or, to put it another way, queer is in the eye of beholder. Especially when the beholder is, you know, desperate. My grandmother had a box of Heyers in the attic, and I still remember those little books so vividly: their flaky yellow-brown dust jackets, and the scent of stale air rising from the pages. I read them all, every single one, but you always remember your first. Mine was The Quiet Gentleman, one of Heyer’s rather disregarded works, I think. The hero, Gervase Frant, the Earl of St Erth, returns to his deceased father’s estate to claim his inheritance, only to discover his family aren’t mad keen on the notion. Cue mystery, intrigue, attempted murder, & etc. The atmosphere is rather gothic, at odd variance with the deep thread of anti-romanticism that runs through the whole novel. It is, in essence, the love story of two deeply sensible people who find themselves caught in a maelstrom of drama and silliness. It’s not zingy or lively like some of Heyer’s other novels, but it’s adult and oddly satisfying. Also, both Gervase and his eventual romantic interest, Miss Morville, are slightly out-of-step with their worlds, and the people around them; they have each cultivated their own resistances. Miss Morville wields her placidity like a weapon and Gervase… oh Gervase:

Then I found Georgette Heyer. But AJH, I hear you say, there’s nothing queer about Georgette Heyer. And maybe you’re right, but identification is more complicated, and more fluid, than the literalities of personal similarity. Or, to put it another way, queer is in the eye of beholder. Especially when the beholder is, you know, desperate. My grandmother had a box of Heyers in the attic, and I still remember those little books so vividly: their flaky yellow-brown dust jackets, and the scent of stale air rising from the pages. I read them all, every single one, but you always remember your first. Mine was The Quiet Gentleman, one of Heyer’s rather disregarded works, I think. The hero, Gervase Frant, the Earl of St Erth, returns to his deceased father’s estate to claim his inheritance, only to discover his family aren’t mad keen on the notion. Cue mystery, intrigue, attempted murder, & etc. The atmosphere is rather gothic, at odd variance with the deep thread of anti-romanticism that runs through the whole novel. It is, in essence, the love story of two deeply sensible people who find themselves caught in a maelstrom of drama and silliness. It’s not zingy or lively like some of Heyer’s other novels, but it’s adult and oddly satisfying. Also, both Gervase and his eventual romantic interest, Miss Morville, are slightly out-of-step with their worlds, and the people around them; they have each cultivated their own resistances. Miss Morville wields her placidity like a weapon and Gervase… oh Gervase:

All that could at first be seen of the seventh Earl was a classic profile, under the brim of a high-crowned beaver; a pair of gleaming Hessians, and a drab coat of many capes and graceful folds, which enveloped him from chin to ankle. His voice was heard: a soft voice, saying to the butler: “Thank you! Yes, I remember you very well: you are Abney. And you, I think, must be my steward. Perran, is it not? I am very glad to see you again.”

Here we have a man whose first on-page acts are to look awesome and be polite. And he continues to look awesome and be polite for basically an entire book, but yet there’s no suggestion that it makes him weak, unmanly, or unattractive. On the contrary, he’s presented as the sort of person an intelligent, interesting woman might want to fall in love with. It’s all so obvious, looking back, but Gervase was my first inkling that masculinity need not be this brute, blunt thing I was told I lacked. It was the first time I really began to question what was inherent and what was constructed. And to see the vast chasm between who I was and who I was supposed to be, not as some deep, irredeemable wrongness in myself but a simple mismatch between what I wanted and what was wanted of me.

Which is where we leave my younger self, I think, with this third reflection. The one that looks neither backwards nor forwards but shows most simply who I have spent my life trying to be: a quiet gentleman.

“And when I first read it, I had no idea what was going on at all. I only knew that I was Bagoas’s age, that he suffered, and was ashamed, that he was different, in the way others perceived him and treated him, and that he survived.”

Yes — this. I’m fascinated by the way literature mirrors for young readers, and how these mirrors don’t require complete (or even partial) understanding of the text. One of my favorite books is The Color Purple, which, when I first read it, I had no idea what was going on at all. I only knew that Celie suffered, and was ashamed, that she was different in the way others perceived and treated her, and that she survived. And I knew she found love, and what that looked like. I responded to it as a girl, and I kept responding to it every time I read the book, right up to my most recent re-read.

Weirdly, The Colour Purple was on my mind while I was writing this, but I realised I was going to have to shut up at some point, so I didn’t mention it. But it’s definitely belongs to that same category for me as these three, and others like them, although now I’m old enough to know what ‘appropriation’ is, I’m hesitant about laying any claims.

I think it’s kind of part of the egalitarian cluelessness of youth that you can just jump into these identifications without self-consciousness. I mean nobody had told me I wasn’t “like” a non-white lesbian woman, and I was looking for connection, not difference, at the time. So, again, I just fell in love with Shug with the protagonist, and didn’t really think, or understand, beyond that.

It’s very strange for me, actually, reading TCP now, as a grown up who has some intellectual understanding of the politics and the context. And I know it’s meant to be A Race Book About Race and A Gender Book about Gender … but I still mainly latch onto Shug singing the blues in that smoky bar, and Celie making her amazing love trousers.

I don’t have anything very constructive to add here. I just want to get follow up comments in email. :) I will say, I had my own moments of recognition in Heyer’s books (Mary and her managing ways in Devil’s Cub, and Sophy and hers in The Grand Sophy, anti-semitism aside; Venetia, of course, but also Avon in These Old Shades). But my true moments of recognition came much later, once I’d already figured myself out. But by then, I knew what I was looking for.

But mainly, just: thank you for this amazing essay.

Yes, I think most simply what I took away from Heyer in a largely ungendered way was that I wanted to be like these people, and be loved by them too :)

I’m very very fond of Avon but he’s an entirely different creature to Gervase. Gervase is all steel and silk, and Avon is just a dangerous motherfucker in heels.

But he definitely ascribes to the look fabulous rule, right?

I think my favourite Heyer heroine is Phoebe from Sylvester, though. I have no idea why, or what it is that distinguishes her. I think it might be because she’s undistinguishable, and so therefore very human, and warm, and areal. Or, as the hero says, a *darling.*

Oh, I love that scene with his grandmother. He’s so despairing. Yes, a *darling*. And, you know, a writer, too. ;)

Also there’s the whole cold, prissy person coming completely undone through love thing. Which is always delightful ;)

Phoebe is my favorite too, to the point that the book always makes me a little uncomfortable. I’m so afraid he’ll yell at her again. :-(

I love this. It’s beautiful and poignant and makes my heart achey, but in the end glad.

I have two sons, and I try to keep in mind that they may or may not be gay, but either way I want to have my eyes open and be aware of the possibility so that I can make sure that they never feel that the way they are, or the way they feel is wrong or weird.

I love that this essay gave me a peek though the window into how it was for you growing up trying to find something to identify with that would make you feel like maybe you weren’t all alone.

I moved a lot growing up and was always the new kid [3 different schools in 1 year, was the record] , always the stranger who didn’t really belong and wasn’t often much like everyone else, so I, in many ways, can identify with that inner yearning to find identification or connection through the characters in the books I read.

Really, AJH, I just loved this piece. Thank you for sharing it.

Yay for wonderful parents! I was/am so careful about this, my oldest had to come out to me as straight. :) Which really, either everyone should have to come out, or no one.

Oh that poor boy. In the general sense, rather than specific to your family, I agree that, in an ideal world, nobody should have to come out ;) But maybe that’s because I’ve always found it faintly mortifying.

Hahahah… that’s what will happen to us, almost certainly.

Aww *hugs*. Thank you for reading it. I know it’s a little melancholy in places but I think part of the reason I was able to write it without requiring too many small violins is because I’m repulsively happy now :) I know exactly who I am, and I’m loved for it, which is all anybody can really ask from life.

Other than my god-daughter, for whom her parents do all the heavy lifting in terms of upbringing, I don’t have that much responsibility for young people. Thank God. I can barely tie my shoes. I mean, I teach them occasionally but that’s a different barrel of monkeys.

But, to me, the important thing is that sense of possibility. I think children are really sensitive to senses of wrongness – where they feel they’re pulling away from what is wanted, or required, or supposed to be. So if you intentionally or intentionally present one thing as the default, and another thing as different from that, even if it’s something small like, I don’t know, preferring books to football, it sort of becomes established. My childhood was full of such absolutes, which was why I was on such a frantic quest for reflection of myself that weren’t my family’s certainties and discomforts. But, also, it was a very different time – a nowhere town in the 1980s. The world is so different now. I feel ridiculously old when I reflect on how much. And there’s just much greater access, to people, and things, and points of connection.

But, in general, childhood can be quite an alienating, powerless time. God, I’m like the anti-Salinger :) Growing up sucks ;) It’s weird because I don’t know anyone who didn’t feel somehow “other” for one reason or other – so I’m just wondering where we get this sense of otherness if most children actually feel lost in some way :) Aaand that is my pointlessly lengthy thought for the evening ;)

” It’s weird because I don’t know anyone who didn’t feel somehow “other” for one reason or other – so I’m just wondering where we get this sense of otherness if most children actually feel lost in some way ”

I came here to rave on the essay, and I find the mostly lovely, wise, and true thought here, tossed off in the comments.

I have successfully “sold” T.A. Barron’s Merlin series to dozens of young teens, all by asking them, “Do you ever get a maddening itching between your shoulder blades? Have you ever thought that maybe, just maybe, it’s because you’re a child of forgotten Fincayra, and your body is remembering its lost wings?”

That would sell anybody, I think :)

I have actually read at least the first one, but I think I was actually a university at the time – so slightly too old really, despite always (and still) taking a deep pleasure in that kind of children’s fiction.

It’s very strange, actually, thinking back over your own reading history – at the time it makes perfect sense, and your instincts guide you where you need to go, but it’s like this convoluted wrestle with being at at the wrong place in the wrong time – like reading books too early, or too late.

I recently discovered Lloyd Alexander’s Westmark series and, oh my god, I am so completely annihilated by it. But I kind of know if I’d read it as a child I probably wouldn’t have noticed. Oh, horrors of war, the loss of innocence and the destruction of ideals – whatevs ;)

Oh my God, the Westmark books. I had picked those up because I loved the Prydain series as a child, and I was utterly shattered by them.

How wounded and *angry* must an author be to come up with a book like THE KESTREL? (Although there are hints of that same passion in the Prydain books, particularly the later ones, now that I think on it)

I met him once, you know, at a library association “thing.” He must have been pushing eighty, but he looked exactly like an otherworldly character in one of his books: tiny and gnarled and fey, with warmth and even a deep joy in his expression, although he was “mingling” with a huge crowd and must have been exhausted.

I was too awed to do much more than babble like an idiot, of course. Besides, what does one say? “Thank you for saving the life of a total stranger?”

I spend most of my professional life feeling like I’m not ever, ever doing enough for the kids I work with.

Sometimes it’s nice to be reminded that just having the right books on the shelves and making them available to the right readers at the right time can be enough to save a life.

As one if those kids who found the right books at the right time, I can say, “Yes, books can save a life”

And what everyone said about the tender loveliness of this essay.

Also: thank you :)

I was a bit awkward about it, as I’m normally, well, I don’t normally write like this. But Ruthie said I should write about love … so I tried :)

Or – in my case – the right readers, at the wrong time ;)

But. Yes.

My public library, in economically depressed northeastern nowheresville, was a squat brown concrete building, with barely the resources to stay open. It was absolutely the unloveliest place you can imagine. And I practically lived there.

It had scratchy brown carpet titles, and I used to sit in a corner, right at the back of the adult section, with my back against the radiator, because I was always cold, and read whatever came my way. By that stage there’d been tacit agreement that I could. I never took the books away because I didn’t want anybody to know where I was, or what I did.

But every now and again, one of the librarians would bring me a cup of really sweet, milky tea, in a big white, chunky mug, and just leave it next to me. I never actually said thank you for this, because I was too shy, but it kept on happening.

Very strange mix of memories really, air that always tasted of salt, scratchy carpet titles, and mugs of tea made by strangers.

Good Lord this was good.

That’s all I can say.

Thank you, that’s very kind. Makes me slightly less self conscious about babbling everywhere :)

Babble away, it was lovely!

Thank you for this essay. I spent my teenage years with Renault and Heyer amongst others, so for me this was poignant. You brought up past feelings for me. Feelings of empathising with book characters more than with real life people. Feelings of being understood and understanding in turn. Thanks once again.

Sorry, I fell down an etiquette black hole because I wasn’t sure if I should be still talking on an old post after a new one went and then angsted for about eighty million days before finally deciding I’d rather be impolite by answering in an untimely fashion, than impolite by not answering. So thank you for the comment, sorry for the hand-wringing based delay.

It feels so banal to say it aloud but books are so important. I think when we’re young our access to the world – or more specifically to *other* worlds – they’re sometimes our only access to ways of thinking and feeling and being that aren’t the ones around us.

I’m sorry you, too, were looking for yourself in books – but it feels weirdly good, doesn’t it, to look back from who, and where, we are now :)

Ah, Mary Renault. Your post brings back such wonderful memories. I was a teenage girl when I discovered her. I picked up “The Charioteer” in a Munich train station bookstore because I found the cover striking and I just really fell for the way Renault wrote and something about her characters just spoke to me. I read all her other contemporaries and her Greek books too but The Charioteer is still my favorite because it was my first exposure to Renault’s writing.

As for Heyer I haven’t gotten to “The Quiet Gentleman” yet. Of the ones I read so far my favorite male character is Avon, such a fascinating and dangerous man. And still the most formidable character as an old man in “Devil’s Cub”.

Oh God, The Charioteer absolutely kills me. Even today, I can barely read it. It’s an amazing book, an important one, but … it’s one of those books that really makes me chafe at the boundaries of acceptance. I always remember the scene where Ralph takes Laurie to the awful party – and that sort of troubles me because it’s *such* a stereotype of the “gay lifestyle”, but at the same time … that’s kind of the point because that intense, self-fulfilling, sterile interiority is what happens if you force a group of people underground and deny them the freedom to just live and love openly. And even though a lot has changed since then, so much hasn’t – it’s still *not enough*. So I get all hot and angry and hurt, and it’s a mess :) That’s why I tend to cleave to Renault’s classical-world set books. Queer love is, of course, still a major theme, but it’s liberated social context. Or rather part of a different one.

The Quiet Gentleman, most people seem to agree, isn’t one of Heyer’s best. But I do love Gervase – and I think I probably have more hope than being like him, than I do of being like Avon ;) I love These Old Shades as well, though. Avon is one of those heroes you feel is genuinely dangerous, not just a pussycat with a nasty growl. Also he has excellent taste in shoes. More heroes should.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful, heart-wrenching, essay, Alexis. I enjoyed this line -“To this day, The Persian Boy remains one of my favourite books, reached for as instinctively as a partner’s hand in moments of distress or uncertainty.” Beautiful. We all have a book that we take out and pet don’t we? I’m happy that despite the lack of credible role models in literature (and I’m sure on tv and in movies) while you were growing up, you found your own that you could respond to. As an adult, you seem to have created a genuine, authentic life for yourself. No hiding, no subterfuge, just all you, twenty-four-seven. Congratulations. I hope it feels great!

-Michele

Thanks Michele, and yes – it does feel good :) It’s partly why I could write this post, I think. From a place of feeling content, and a little bit triumphant. And without requiring too many very small violins ;)

Pet-books are so important. I guess we all have our comfort mechanisms, but there’s nothing to beat – for me – the warm feeling you get from a familiar book. Also the way you respond to books changes over time (I’m glad, for example, to have comfortably abandoned my desire to be a Persian eunuch) so it’s can also be like this odd little trip into your own past selves.

Thank you again for the kind words :)