When my husband and I were first falling in love, we’d hang out in his attic apartment in Ames, Iowa on Monday nights.

When my husband and I were first falling in love, we’d hang out in his attic apartment in Ames, Iowa on Monday nights.

The ceilings were sloping, and there was a big Robert Smith poster looming over everything. My future husband was skinny and always worried something in his hands, his thumbs square to his pretty forearms. His dark hair was always too long, and even though he was this overly confident, superiorly funny Minnesota boy, he could only hold eye contact with me for so long before he’d look away, a self-effacing smile on his face as if he was couldn’t believe that he was so worked up over a girl.

Who was me. Who couldn’t believe I’d snagged the attention of this boy, this funny boy with green eyes and dimples who had such an accurate bead on me, right away, that he sauntered, sauntered up to me one day and said, I’m going to go get a coke. But first, I want to let you know that when I come back, I’m going to ask you out. And I swear, it will be fine, better than fine.

So on Monday nights, with this beautiful boy in his attic apartment, we’d watch The X-Files on his Zenith television, and to tune it in, he’d have to climb out the little round attic window of his apartment and hang off the side of the house and rest this antennae attachment he got at Radio Shack in the rain gutter.*

Then he’d swing back into the apartment, and shove his dumpy sofa in front of his Zenith, and then he’d pour me a beer in the one beer glass he owned and drink out of the bottle for himself. And we’d watch Mulder and Scully with our legs crossed over the other on his dumpy sofa and marinate in the second-hand sexual tension until, well. Let’s just say that Robert Smith learned some things.

Oh, it was fine. Better than fine.

Everything about those Monday nights, every little thing about them, is what I am trying to recreate when I watch a movie.

I want everything to be low-stakes and off-kilter. I want the underpants feelings to come slow and easy. I want to hardly be able to believe what I’m watching, but it to all be okay because some love in the story makes it okay. I want nerdery and strange images and I want to cross my legs together with a cute Minnesota boy who likes all the parts I like at the same time.

Actually, that Zenith was the last television we ever had, and it died nobly, during an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer somewhere inside our first year of marriage. Nowadays, when we watch something together, we steal an unstable 90 minutes sometime after our son falls asleep and before we drop from exhaustion. We lean back on our martial bed, with a laptop balanced on our knees and the volume so low we breathe shallow so we can hear the movie and if our child cries out for us.

Somehow, it’s fine. Better than fine.**

The first time we watched the movie Sidewalls (Medianeras, written and directed by Gustavo Taretto, 2011), ensconced in the bedroom of our urban brownstone, the streetlights shining through the windows, the even and sleeping breaths of our kid a few paces away, we looked at each other as it opened with one of the most beautiful monologues we’d ever heard in film and grinned.

It was about the irrational architecture of Buenos Aires, how it had grown out of bad logic, short buildings next to tall ones, small buildings built to make room for even smaller ones, and how this irrationality reflected its people perfectly. How a shoebox apartment lost in the swell of this overgrowth led to depression and anxiety and pain, and how really all the pain and disconnect of the world could be attributed to builders, to architects.

We grinned, because it was beautiful, because we were sitting, knee to knee, a laptop balanced on top of them, in one of the most irrational brownstones in Columbus, Ohio—four narrow stories tall, worked over so heavily in plaster and carved wood and staircases that we sometimes don’t even know if the other person is even in the house and we spend good parts of our day going up and down stairs and looking in all the nooks that 19th century people had some use for trying to find each other.

Just like we’ve been trying to find ourselves, and each other for the last few years.

Unlike that 400 square foot attic apartment, the garrets sloping so close over our heads we had to push the dumpy sofa into the middle of the room to watch TV. So close and small we always knew right where the other was, and we were almost always close enough to touch.

So of course, Sidewalls, is a love story. Perfectly low-stakes and off-kilter, and wonky. The deliverer of our monologue is Martin (Javier Drolas), a shoebox apartment dweller, who until recently, completely confined himself to his apartment, for years, due to severe agoraphobia. He was cured, he says, by a psychoanalyst who told him to go into the city with a camera, where Martin documents the unbeautiful. Because he is also phobic of all transportation, he only goes by foot, and carries a “panic backpack” outfitted for every contingency with tools, first aid, computer memory, and antibiotics.

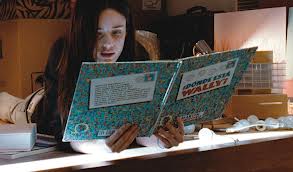

Every building, says Mariana (Pilar Lopez de Ayala), our heroine, has a side whose only use is to differentiate between us, divide us, to show the wear and ugliness of the building. This is the sidewall. Home only to cracks and graffiti and advertisements. She is an architect who has never built anything, not a building, not a bathroom, she tells us. She works as a window dresser, building ideas in non-rooms that are neither inside or outside, and tells herself that if someone looks at one of her displays, and likes it, that this is the same as liking her. She’s learning to be alone after finding that the man she loved was a stranger; she’s learning to live, again, in the 8th floor apartment she abandoned for him, eight floors up and alone and she’s phobic of elevators. She brings her window display mannequins to her apartment for company, to talk to, to make love to. And obsesses over her childhood copy of Where’s Waldo? Despairing because there is one puzzle in the book she has never solved, has never found Waldo—Waldo in the City. She believes she has no choice but to accept that this is a metaphor for her loneliness, her inability to find herself.

The sidewall of her building faces the sidewall of Martin’s.

So this is a love story divided. There is no light between them, and though they share the same street, and there the smallest geographical space between them, we watch them just miss each other, again and again.

So this is a love story divided. There is no light between them, and though they share the same street, and there the smallest geographical space between them, we watch them just miss each other, again and again.

Yet, this is not played as a farce, only three times are they within a few feet of the other, looking the other way, or in the dark. How they really miss each other is by their inability to connect and find lasting love with anyone else, and with their personal journeys of self-discovery and increasing readiness for love. And here’s the thing—that’s why this movie is everyone’s wonky love story. Because, we’re all sidewalled away from the other, and if we haven’t found love, it’s like Mariana’s Waldo, he’s there, it’s just our own blindness. We watch Martin and Mariana yearn for the same things, and cry at the same movies, and sing along to the same summer ballad. We also, without seeing them together, have the ability to discern where they are complements.

I think about the Monday nights before I met my husband, watching Mulder and Scully, while he sat in his attic apartment with the window open, the crickets singing, watching Mulder and Scully. We were already having our love story, in a way.

Or at least, that’s the hopefulness of all of this. It should be impossible to tell a love story about two people falling in love before they’ve ever met, or even know the other exists. That’s the wonk. That right there, the telling of this love story. The wonk is not that Martin is phobic and a hypochondriac, it’s not that Mariana smashes tea cups when her neighbor’s piano playing gets too sad, and the wonk is not that she gets her lip pierced. It’s that we watch them fall in love, utterly in love, and they don’t know the fact of the other’s existence until the last 45 seconds of the movie.

Yet, the movie is utterly romantic and dear for all of its failed dates with pothead dogwalkers and impotent swimmers, for its random and heartbreaking sidebars on architecture and cyber sex. Every time Martin smiles at something we know, we just know Mariana would also smile over—our belly swoops satisfyingly. Every time they express their longing for connection without wires or walls, we curl our toes in anticipation of their finding each other. Meanwhile, we see that every foray they make into their own, personal happiness is one more brick demolished out of the sidewall between them.

The wonk is in the telling. In this impossible trick of showing us how we fall in love before we ever meet our beloveds.

Sometimes I ask my husband to, tell me something about you. Something I don’t know. Something that happened to you before we even met. These are my favorite stories. Even the most mundane recollections fascinate me: once I walked a mile in the rain to buy a girl I met in a bar clove cigarettes because she said she was craving one. When I first came to college, I didn’t know which machine was the washer and which one dryer and it made me so angry, all the things we just expected my mother to do. There is always something about these stories that feel familiar, even if I have never heard them before, because they are the things that make my husband who he is, and I love my husband. They are the things that made him ready for me.

This movie is a perfect 93 minutes long, just exactly at the time we can spare after a child’s bedtime and before our own. But the first time we watched it, we started it over and watched it again, and talked all through it, in low voices, pointing out all the things we had noticed the first time. Not unlike that hour, year ago, we earmarked for the other every Monday night, the time we’d see each other even if we hadn’t made plans that week to see each other. I’d climb the stairs to his attic apartment and knock, and he’d open the door and say get in here, what took you so long? Even though I came the same time every Monday.

How do you find a person when you don’t know what you’re longing for? Mariana wonders. That’s it, exactly. Our love story starts when we ask the first questions of ourselves, when the sidewalls are intact. We have to know ourselves, what we long for, what we don’t want. We have to walk a few miles in the rain for a pretty girl who won’t be the one we settle on. We have to walk our dogs with a pothead and have terrible sex with someone we met at a public swimming pool. We have to first, be true to ourselves and pierce what we want to pierce and be afraid and then unafraid.

How do you find a person when you don’t know what you’re longing for? Mariana wonders. That’s it, exactly. Our love story starts when we ask the first questions of ourselves, when the sidewalls are intact. We have to know ourselves, what we long for, what we don’t want. We have to walk a few miles in the rain for a pretty girl who won’t be the one we settle on. We have to walk our dogs with a pothead and have terrible sex with someone we met at a public swimming pool. We have to first, be true to ourselves and pierce what we want to pierce and be afraid and then unafraid.

We have to be better than fine.

We are all irrational, a product of bad logic, we’re the short building next to the tall one. Somehow, we find each other. Mostly when we find ourselves.

This is a spectacularly wonked movie, and not primarily because its hero and heroine are. Its wonk comes from what it chose not to show us. And what it did. Just like love, it should be impossible.

Sidewalls is currently streaming on Netflix. Or available to rent from Amazon.

*When it rained, we couldn’t watch The X-Files. But what we did instead was so much better, I sometimes hoped for rain.

**Fourteen years in June.