I recently read Carrie Lofty’s His Very Own Girl, and it has thrown me into a mental tizzy regarding historical romance and escapism and what on earth it is I want from the historical subgenre. Such a tizzy, in fact, that I kind of just want to tear madly at my hair and say, “I don’t know, all right?” and then eat a large chocolate chip cookie. But I’m going to give this a go anyway, because Lofty’s book tapped into some questions I’ve been asking myself for a long time, and I’m interested in throwing them out to my wonk-o-peers and finding out what you guys think.

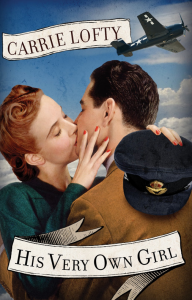

So, first, Lofty. His Very Own Girl is a romance set in the English Midlands during the latter part of World War II. The hero, Joe, is an American medic with a dark past (oh, ex-con heroes, how I love you), and the heroine, Lulu, is an Englishwoman who flies planes for the Air Transport Authority, which was a British civilian unit that ferried military aircraft around England (and to a very limited extent Europe) during World War II. Early in the war, her parents (also pilots) were killed while flying over Egypt. Her English fiancé fought in Europe, came home, and committed suicide shortly thereafter. She survived the Blitz in London, then joined the ATA. She is a supremely dedicated pilot; she deals with grief through action.

So, first, Lofty. His Very Own Girl is a romance set in the English Midlands during the latter part of World War II. The hero, Joe, is an American medic with a dark past (oh, ex-con heroes, how I love you), and the heroine, Lulu, is an Englishwoman who flies planes for the Air Transport Authority, which was a British civilian unit that ferried military aircraft around England (and to a very limited extent Europe) during World War II. Early in the war, her parents (also pilots) were killed while flying over Egypt. Her English fiancé fought in Europe, came home, and committed suicide shortly thereafter. She survived the Blitz in London, then joined the ATA. She is a supremely dedicated pilot; she deals with grief through action.

Lulu dances with soldiers, dates them, occasionally kisses them, but never sees the same guy more than once. She can’t go through what she went through with her fiancé a second time.

Until Joe.

The first half of His Very Own Girl is Joe and Lulu engaged in a courtship dance. She doesn’t want to fall in love with him but can’t help himself. He’s drawn to her but doesn’t understand why she would need or want to fly airplanes and put herself in danger. (It doesn’t help that when he meets her, she’s crash-landing a plane right in front of him.) He objects to what the war has done to gender roles and looks forward to a time when the world can go back to the way it used to be. Lulu finds everything about wartime gender roles liberating and has no intention of ever giving up flying planes. Their clashing views come up repeatedly and are impossible to paper over.

In addition, Joe also has a violent past that he tried to escape by enlisting. Of course, it chases him to Europe and throws a spanner in the works of his budding romance with Lulu.

But they persist. They are in love. D-Day arrives, and Joe goes to France. The rest of the book has Joe and Lulu corresponding, visiting once on a weekend pass, and trying to work out and/or bridge their differences to discover whether they have a future together. (Spoiler: they do.)

While I had a few quibbles here and there, I found His Very Own Girl to be engaging, well written, and very well researched. I love the idea of historical romance set in different periods and genres than the standard ones, and I’d looked forward to reading this one ever since I first heard about it.

And yet.

World War II was total war — much more so in Britain than in the United States. It affected every facet of everyday life in terribly intrusive ways for a terribly, terribly long time. Rationing in Britain began in 1940 and didn’t completely end until 1954. One of the things I admire about Carrie Lofty’s world-building in His Very Own Girl is that she gets that. The war is everywhere. It infects everything. It is a constant factor in Lulu and Joe’s relationship, the catalyst for their meeting, their disagreements, their reunions, their hopes and dreams, their inescapable sorrows. It is hard and mean and horrible.

I loved this about the book. But I hated it, too.

His Very Own Girl made me sad. Not just now and then, or at the dark moment, but frequently, throughout. Sometimes it was happy-sad, the way I get when I think about how beautiful humanity can be in the midst of trauma. Sometimes it was nostalgic-sad, as I thought about my grandparents World War II story and how the war shaped the generations that lived through it. Sometimes it was ordinary sad, i.e., Damn, this is depressing. I am sad.

When I think about the book now that I’ve finished it, my enduring mental impression is dark. And I’m not sure that works for me. It isn’t what I’m looking for in a romance novel. It doesn’t make the book a bad book, by any means, or one I’d discourage someone else from reading — it just makes me wonder, you know, what is it? Is it a romance novel if it makes me feel this hopeless, or is it something else?

Is it even possible to write an escapist love story set in the context of an inescapable war? And is a romance novel that isn’t escapist really part of the romance genre?

These are difficult questions for me — perhaps more difficult for me than for others, because I’m a historian by training. When I first started reading romance, I wouldn’t read historicals. I read a few bad ones, and they bothered me because they weren’t set in the real past. They were set in a fantasy past. Eventually, someone tipped me in the direction of excellent historical romance, and I’ve been enthralled with it ever since — but simultaneously annoyed, from time to time, by its insistence on skimming the surface of history. Why so many Regencies? Why so many aristocrats with daddy issues? Why so many books that aren’t just about aristocrats with daddy issues but aristocrats with daddy issues who aren’t even confined by the social mores of their own time?

But perhaps Lofty’s His Very Own Girl is a case study in the why. It is not an accident, after all, that the most popular historical romances are about earls with daddy issues who fall in love with heroines who are unfettered by social convention. This is what romance readers want, because it is easy.

Yet I persist in thinking that I don’t want that — or certainly I don’t always want that. I’m a Wonkomantic. I subscribe to the Wonk-o-Manifesto, which says, “We like our protagonists less conventional, our conflicts less tidy, our endings less certain. We want escapism, but we want it with a nice, stiff shot of human frailty.” It also says, “We want the whole messy spectrum of human behavior, packaged up for consumption in romance novel form.”

And I really think this is true — that I do want this. But it seems to be the case that I only want it if it satisfies me in particular ways, and not if it makes me feel excessively anxious or unhappy or depressed. I want some anxiety, but not too much. Some tears, but not too many. Some gritty reality in the portrayal of history, but not so much reality that I get all swept up in thinking miserable thoughts about the past.

When it comes to a book like His Very Own Girl – and I don’t want to single Lofty out, because I’ve read other books that similarly troubled me (Kinsale’s Flowers from the Storm comes to mind) — my brain and my emotions part company. My brain is pleased at how wonky and different and difficult these novels are. But my emotions say, This is not enough fun. I end up torn and feeling — well, like not much of a wonkomantic.

What do you guys think? I don’t have all the answers today, but I’m interested in having the conversation.

There’s no such thing as a romance novel that isn’t escapist, because escapism is in the eye of the reader.

Speaking as someone who reads romances for many reasons, escapism and fun being two of them but not all, what I can say is that it depends on the reader and how they define escapism and even romance. To me, gritty and depressing mean enjoyable and fun. I like my romances sad and angsty, and I get much enjoyment and happiness from them. Unlike you, I like feeling excessively anxious, because it usually means that the emotional payoff will be fantastic. It’s a bit like one of those sex scenes where the hero torments the heroine by pleasuring her without letting her orgasm, and then after so much torture she explodes and is so good that all her emotional issues are magically cured by his mighty peen. That’s how I feel with these books. I love fun, light stories, but they don’t get the same payoff from them. As long as I get a HEA I can believe in, it doesn’t matter how terrible the journey to get there was. Of course, one could argue that some journeys are so tortuous that make the HEA impossible, so I guess that I don’t have all the answers either.

Great post!

Thanks, Brie! I think I might be one of those people who argues that if the journey is too tortured, the HEA is . . . not impossible. But colored by the torture. (And those sex scenes with the orgasm torture? I don’t enjoy those at all! Intellectually, they’re fine. Emotionally, they do nothing for me.) But I think you’re right, “escapism is in the eye of the reader.”

Hmm. I think I know what you mean — I actually have a GoodReads shelf called “too sad” — but I didn’t feel that way about this book. It did scare me and more so than a typical romance, But like Brie, I like being anxious, within certain limits. I much prefer my anxiety to come in the romance genre, because I can have that assurance that all will be (reasonably) well by the end. And there has to be a good payoff.

I could tell you didn’t from your review — and that was one thing that made me think, “Well, self, it’s entirely possible that this book pushes buttons for you that other people don’t have.” But it did make me ask many interesting questions, which I always enjoy.

I haven’t read that Lofty book yet – it’s on Mt. TBR – but I will say that I find the more difficult romances to be the most uplifting, actually. The message I get from them mirrors my own life experience. No matter how terrible your life looks from the outside or how chaotic the world is around you, life goes on. Happiness isn’t predicated by perfect conditions. People laughed, smiled and fell in love during WWII, during the Civil Rights Era and during the Bush II Era. I like seeing people endure and survive. It leaves me hopeful.

Ridley… isn’t this the same attitude that pisses you off when people claim to find something “inspirational?” What do you perceive as the difference?

My issue with able-bodied people finding disabled people “inspirational” is that it’s about using ableist assumptions of disability to add meaning to able-bodied life. It’s taking a disabled person’s story and making the able person the subject of it.

The romance novels I like best, with the “difficult” themes, show normal people getting on with it in their own way despite outside circumstances that would lead an observer to think happiness was impossible. Ideally, the takeaway at the end is that every life comes with challenges, and while some problems seem bigger than others, life goes happily on.

Huh. I’m still not seeing how the pictures of the disabled soldier and his girlfriend don’t show exactly that.

The difference for me is that I don’t see challenges as proof that the couple’s love is extra lovey or that extraordinary times mean the people who survived were extra heroic. I just see it as reflective of human nature, and I think that connection makes a fantasy easier to indulge in.

I can totally see that. I do enjoy books about survival/endurance — but I’m not sure I file them away in the same place in my brain as romances. There’s probably no very good reason for that. I think, though, if I’d encountered Lofty’s book as something other than a romance — and compared it to something other than other historical romances — I might have felt differently about the experience of reading it.

I’ve been thinking about this all day and I think perhaps my threshold is a moving target. I do like sad romances and I love angst and usually the more the better – but for me it’s a pay off thing. You can drag me way down, but then the ending has to be super bright. Super hopeful. I have to believe the dark days are behind them and they’re okay. So if the ending doesn’t make all my pain go away – it doesn’t work. really interesting topic!

The Lofty book is on my TBR too – maybe next…

I think your comment comes closest to mirroring how I feel about dark books. When I see a movie or a TV show, I often have an enduring color impression of the film afterward. Like the first Tim Burton Batman movie? BLACK. Everything in that movie was BLACK in my memory, and as a result, I never want to see it again. And in the same way, a really angsty, dark romance will create a dark mental impression that the ending has to go a long way to brighten up. If, after I’m done, I think back on the book and remember mostly the blackness, I won’t feel good about the book. Sometimes I will be impressed by the ending and BELIEVE the ending but still not have happy feelings about the book, à la Flowers from the Storm. Loved the final scenes of the novel, but I don’t think I can ever read it again.

Payoff is an exceleny yard stick to measure escapism by, IMHO. I like that, Molly. Thanks!

I don’t do sad books. I will put them down/delete them from my kindle. I like my conflict wonky as far as character traits, i.e. damaged people finding love with other damaged people and not necessarily having to fix all the damage first. But I draw the line at depressing circumstances. If a book starts out in a place that is too dark, too depressing, I won’t keep reading…unless the author gives me a ray of hope to cling to and a compelling character to root for.

I demand a HEA. I also demand a few happy moments in the book. But it’s a fine line. If a mid-point is too happy, it feels like an ending. Tension plummets. I get bored.

Thanks for being honest, Ruthie, about feeling two different ways about a bleak, war-time setting. May I ask, who gets the bigger vote when you’re selecting a book to read, your head or your heart?

Now there’s an interesting question. My head usually wins, because if a book is all heart, my brain gets bored. I’d rather read something frustrating and flawed than something that makes me happy but I forget it ten minutes later. I’m sure I’ll remember this Lofty book for a long time; can’t say that of the three or four other books I read last week.

(Replying to Ridley) Ah, I see. Thanks for explaining.

Very interesting post. Here’s what I’m struggling with: what do you make of the tendency in Rom to whitewash certain eras of history? Because I don’t know if there’s any era free of the kind of darkness you’re talking about here. And yet I’m so very wary of the way history is de-historicized in so much Romance to keep that happyhappy thing going. Or is it just that different readers will have different reactions to different historical settings?

I guess what I’m worried about authors feeling that they cannot write about dark historical moments, because they are afraid readers will not embrace these books. I cannot tell you how frustrated a lot of the Native American aka “noble savage” Roms make me, with the historical whitewashing and erotic fetishization of certain racial and cultural stereotypes.

And then there are the Medieval Roms that make the past look like an unremittingly dirty, violent, disease-ridden hole. And yet they’ve been so popular, which is kind of interesting when you think about what *has* been taboo in the genre. It feels like there’s some pattern here, but I cannot completely make it out.

You’re right — there’s no era free of it. And honestly, that’s one reason I struggled so much with my reaction to this book: I wanted to be delighted with it, in order to encourage more books to be written with more far-flung historical settings and subjects. I *do* want authors to write about dark historical moments and pull drama from all the different sources the past offers. (With few exceptions, I can’t even read romance with Indians in it, for just the reasons you mention.)

My husband teaches U.S. history, and he’s mentioned before the tendency of his students — most of them 19-year-old white kids from Wisconsin (though not all) — to identify with certain points of view and sides of arguments in the past as “us.” “We” were abolitionists, they will say, with no self-consciousness, whereas “they” were slaveowners. We were in favor of Transcendentalist thought, not narrow-minded Puritanism. “We” settled the West, but “we” didn’t employ Chinese wage-slaves to build the railroads. I think it takes a certain amount of flinty intellectual honesty to call bullshit on this, and also a willingness to empathize with subjectivities very different from one’s own.

But romance has “heroes” and “heroines,” and I think there’s only so far one can push a romance character’s subjectivity before it becomes unrecognizable and repellent to the reader. Which poses real barriers to portraying the past in anything like its full spectrum (setting aside the point that even historians don’t have access to anything like the “full spectrum” of the past, because the sources that get preserved are primarily the literate, elite voices).

Long-winded reply, sorry. I’m very interested in this subject, obvs. ;-)

Your answer, though, lines up with me mentioning GWB. I’d say there’s a good chance that people 100 years from now look at 2001-2009 as a miserable period in history. Two ugly wars, a nasty terrorist attack, severe limits to civil liberties and a huge recession. Yet, I’m sure all of us remember finding joy during those years, even while some of us felt these effects directly. Why wouldn’t people in other periods have had similar experiences? That was their normal, just like this was ours.

That make sense?

Oh, absolutely. I agree with that. And I’d love to see more books from disparate periods so I can find out if my reaction to this one is really about the book or the period or some random idiosyncrasy.

I’m actually working on a post that tackles the hero and heroine thing, so I’m going to put that aside until I have something coherent to say, but I think your mention of the Puritans is a great example of the complexity to which you’re referring.

There is an incredible misunderstanding of who the New England Puritans were and what they stood for. In fact, many of the views that are routinely and popularly ascribed to them have actually been handed down through the Victorians. New England Puritans were not anti-sex; in fact, couples who were remote from a magistrate lived together like couples do today, moving on if and when the relationship ended, without benefit of marriage or divorce. Pregnancy before marriage was somewhat routine (after all, wouldn’t you want to know that your union was a fertile one?), and couples were not fined unless they failed to marry before the quickening (i.e. onset of the second trimester). Ditto abortion, which was not even recognized as anything bad (let alone criminal), as long as it occurred before the second trimester.

Forgive the geekitude there, but I’m pointing these things out merely to highlight the way in which moments in history are often reconstructed in ways that are already warped. And then those perceptions are replicated in our fiction, and they become entrenched as “facts.” In genre fiction, I think the important role of mimesis makes this process even more common and potentially problematic.

Not that I expect Romance to ever completely untangle these problems, because they’re not just about Romance, and in some cases, the symbolic misconstruction of history serves interesting narrative purposes (I think the sheikh narratives can do some fascinating subversive work, for example).

But at the same time, I think our responses as readers are not always to particular historical moments, but to the reconstruction of those moments as they are negotiated against our own internal constructions of these time periods. NOT that you, as a reader, should not be able to have and articulate exactly the reaction you had to Lofty’s book. I just think there might be some reconditioning that’s happening with books like Lofty’s — that is, assumptions many of us have about particular ways in which history is and can be used in Romance are challenged in certain books, and it’s uncomfortable, perhaps even unromantic. What I don’t know (for lots of reasons, many of which rely on my own lack of knowledge), is whether there’s some shared conditioning that makes certain time periods seem more problematic to write about, and whether that conditioning is related to unsound or incomplete perceptions of historical reality.

In the end, it may not matter; it may just boil down to books and like and books we don’t, for any number of reasons. I just get fascinated by these macro questions, especially given the ways in which some of our most problematic eras — in terms of the identification you talk about re your husband’s students — can become so powerfully fetishized and whitewashed in the genre, while other eras and representations are seen as collectively taboo (like the years leading up to WWI in the UK and USA).

“But at the same time, I think our responses as readers are not always to particular historical moments, but to the reconstruction of those moments as they are negotiated against our own internal constructions of these time periods” — a fascinating point, and it strikes a chord with what I was trying to get at with my paragraph about Lofty’s portrayal of total war. I really enjoyed this aspect of the book as a historian, because World War II fiction (particularly from the American side) has a tendency to paper over the endless, relentless GRIND of the war and its invasion into every aspect of social life. But there is discomfort there, as well — a gravel-ish grinding of plates between the past that happened, the past I studied, the past of fiction, the past of romance. I don’t know how to negotiate it as a romance reader and writer. I do enjoy that it’s possible to experience it at all, through reading Lofty’s book. One of many reasons I commend her for having written it, and her publisher for publishing it. :-)

I think maybe what we’re circling is the distinction between a book being genre Romance and being romantic to individual readers.

Over the years, I’ve seen arguments and reviews that punish certain Romances for being unromantic (and in some cases claiming they cannot be Romance at all). And there’s a certain allure to that argument, because Romance should be romantic for its readers.

But as all of us are noting, what’s romantic will vary among readers, and, as you say, that’s one reason it’s so important that authors and publishers keep pushing these kinds of stories out there.

I happen to adore Black Silk; it’s probably my favorite genre Romance of all time. But I know of readers who not only find it unromantic, but who argue that it’s not really Romance. Those classification arguments are fascinating (especially when you get into the women’s fic v. Romance debates), but I know that’s not what you’re undertaking.

Still, I think you’ve hit on a good way of making that distinction between genre and book characteristic in a way that allows for a broader, more diverse conception of what lies within genre boundaries, even if it does not appeal to every reader as romantic.

@Robin — I love Black Silk. Loooooove. But I’m not certain it’s a genre Romance. It’s right on the line, in my opinion. But it’s definitely romantic, to me. And awesome.

Why do you think it’s not (or almost not) genre Romance?

Because the beginning is so slow, and so lit fic. It’s like this long, placid character study, even before they’re introduced to each other, and then after, it takes them hundreds of pages of studying each other to figure out what it is they even want. It’s as though the romance happens to them without their knowledge — not without the reader’s, because the reader knows it’s a romance, but almost.

I guess I’d classify those characteristics as stylistic not defining re. genre requirements & boundaries.

In fact, one of the reasons I love the book so much is that the evolution of the relationship feels so organic to me.

One of my frustrations with a lot of Romances is that they feel too overdetermined, forced instead of followed by the narrative, if that makes any sense.

I found myself nodding along with Brie’s comment that “I like feeling excessively anxious, because it usually means that the emotional payoff will be fantastic” and Ridley’s comment that “I find the more difficult romances to be the most uplifting, actually.”

But then I remembered my least favorite romance ever, a 1970s book called Purity’s Passion by Janette Seymour (it was reviewed by RedHeadedGirl for Smart Bitches, and you can find the plot summary there). I read it over 20 years ago, and there are still some scenes I wish I could wipe from my mind.

Anyway, that made me get your POV better. I haven’t read the Lofty, but Flowers from the Storm was uplifting for me, so I suspect my threshold for angst is higher than yours. Still, I do understand where you are coming from. If a book is downright nightmarish, and the happy ending can’t serve as an adequate counter-balance, then it doesn’t work for me.

Still, I look at those books as poorly written romances, rather than something other than a romance. I was just having this discussion with Ridley a few days ago. Maybe because I cut my romance reading teeth on 1970s and 1980s books, I’m uncomfortable with saying that a book has to be satisfying to me in order to be a romance. I might say, “it’s not romantic to me” or even “I don’t personally consider it a romance” but saying “it isn’t a romance” is troubling to me.

I remember being taken aback by this AAR review of Lydia Joyce’s Wicked Intentions, because for me that book was a romance. Because the definition of romance is in the eye of the beholder, and I have enjoyed some books that weren’t romances in the eyes of other readers, I would rather the genre’s umbrella be large and inclusive. There are books I have no interest whatsoever in reading, books that might depress me or even horrify me, but even if they aren’t romances in my eyes, personally, I don’t want to be the arbiter of whether or not they fit in the genre.

Don’t get me wrong — I loved Flowers from the Storm. I think it’s marvelous. I wouldn’t un-read it. I just think back on it, and my strongest impression is of the sense of utter impossibility — not that the hero will be healed, but that the heroine can ever be happy as his wife. And while the ending made me cry and impressed the heck out of me, I still didn’t believe anything would ever be easy about their love.

Which is neither here nor there. My *real* response to your comment is — Yes. You’re right. I don’t want to be the arbiter, either. I am all for inclusivity.

I think what troubled me about Lofty’s book — and again, this is emotional-me, not intellectual-me, because intellectual-me is fully in favor of this book — was that the romance *did* feel satisfying, and I *did* believe it in the end, and yet the whole experience of reading the book made me sad. So I got all obsessive about trying to parse what had happened and why, and what, if anything, that means.

I was going to say that I don’t like the idea of making “escapism” (or maybe we could find something more value-neutral to call it) part of the genre, because it seems like the kind of limitation that will always leave romance at the bottom of the genre totem pole. I’d say romance does not have to be escapist, that it can be gritty and real, but that readers might still prefer to find escapism in the genre and so some books won’t work for them.

But then I thought, many people define the inevitable HEA as escapist in and of itself, and I’m not willing to give that up. And your point in the comments about “hero” and “heroine” is important. If we’re going to define romance protagonists that way, and in doing so say that they still share DNA with the larger-than-life, if flawed, heroes of chivalric Romance, well then, maybe that does mean there’s only so far we can go with historical or contemporary realism. I think there’s a basic expectation in the genre that characters be admirable, despite their flaws. Should there be? I don’t know. I’m trying to imagine how I’d feel about a romance where the hero and heroine were slave-owners and didn’t see a problem with it, and where that wasn’t idealized. I’m not sure I could read that. And yet, I’m sure there were slave-owners who fell in love and who had plenty of good and likeable qualities.

Huh. This seems like something fundamental the genre has to keep wrestling with, and there is no clear way to draw lines. I think it can only be good and productive to keep wrestling.

Thanks for poking my brain. What blog post topic shall I demand from you next? ;)

For whatever reason, the genre totem pole doesn’t bother me. Perhaps it’s just egotism — I figure if I’m interested in it, it has merit, and anyone who disagrees is welcome to go hang out somewhere else. :-)

I agree — it’s worthwhile just to think and talk about it, even if we don’t reach any sort of consensus.

I like thinking about characters as “empathy projects” — your comment about slaveowning romance just made me think, “Oh, that would be fun to write.” So clearly, I’m hopeless. I always empathize with the most horrible people in the past. I actually wrote a blog post about that once, over here:

http://www.ruthieknox.com/2011/05/infanticide-isnt-sexy/

Cheryl Sawyer had a historical romance published in the early 2000s, Siren, in which the hero was the historical figure Jean Lafitte, a pirate who among other things, sold slaves. The heroine, a fictional character, was also a pirate but descended from a slave and his profiting from the slave trade was a bone of contention between them. Though the writing was good, I just couldn’t deal with that aspect of the book.

Janet Mullany had an erotic romance also published in the 2000’s, Forbidden Shores, in which the heroine was an abolitionist and the hero turned out to be part black. However, in the middle of the book the heroine married the owner of a Caribbean plantation. I found that very problematic as well.

I admit that I wince every time the word “escapism” is used in defense or definition of Romance. I’ve come to an uncomfortable truce with it, I think, in thinking about the way that every foray into an alternative world via fiction is a form of mental escape, but I still think the term has specific uses in Romance with which I’m not completely comfortable (especially when the term is used to discourage critical analysis and just plain criticism).

I can understand that. I like the term because it taps into something essential about the way in which I read romance (as well as a lot of other fiction) and where (some of) my pleasure in reading it derives from. But I do see people saying, “It’s an escapist genre, so subjecting it to analysis is pointless. Stop taking yourself so seriously.” And I dislike that. Intensely.

Liz,

Funny you should say that, because my original comment said that I found the idea or Romance as escapism diminishing and slightly offensive. Escapism is not the reason why I read the genre, not even something I usually get from it, although it can be a byproduct of reading, but not because it’s romance, but because I get enjoyment from reading it. But a lot of people do read for escapism and I remembered how my post about the cheating hero was not well-received, and people claimed that they didn’t want that type of realism to intrude in their romances because they read for escapism. So I figured that I should stop being offended by it, and instead wrote that I read romance for many reasons, escapism being just one of them.

Now I wonder if something that gives us joy and pleasure, like a HEA, automatically becomes escapist.

Can fun and great emotional payoff not provide the reader with escapism? Do they always go hand in hand? I think it depends on the reader, but now I must think about this.

Oh, people go NUTS when you talk about cheating heroes. Or adultery generally. I find it kind of fascinating, though it’s not a can of worms I want to open.

I understand where you are coming from with Flowers from the Storm. I remember arguing with readers who felt that Maddy should have embraced her marriage to Jervaulx more quickly and helped him more and sooner. It’s interesting to me that Maddy is the more controversial, less-liked character for many readers, because I had a lot of sympathy for her. I do think that she has a big adjustment to undergo at the end but she seemed happy in the epilogue and I was able to believe that although things would not be easy for them, they would nonetheless be rewarding.

Interestingly, I know one reader who was a doctor whose issue with the book was that for Jervaulx to have a stroke at such a young age meant that he would almost certainly have another down the line.

I had a much stronger reaction to Kinsale’s Seize the Fire, which made it much harder for me to envision happiness in the heroine’s future.

You’ve made me really want to read the Lofty. I have a recommendation for you, a historical mystery with romantic elements set in France between the world wars. It’s A Very Long Engagement by Sebastien Japrisot. Oh, how I loved that book! Whether the ending is happy is in the eye of the beholder. It’s certainly not a romance HEA. But it does have that “happy-sad, the way I get when I think about how beautiful humanity can be in the midst of trauma” feel, and if you’re willing to approach it as one does a book in another genre, it’s truly excellent.

Okay, I think I’m going to drop the italics next time. They seem to wreck the formatting — sorry about that!

All right — I’m scampering off now to download Seize the Fire and Very Long Engagement samples. Will report back. :-)

(And yeah, sorry about the italics. Something wrong with the blog template, I think.)

Seize the Fire is Kinsale’s darkest book, IMO. And it also deals with war. Just to warn you!

It’ll be good for me– extend my research sample! And Kinsale’s such a good writer, I’ll enjoy being wretched.

Looking back on HVOG, I think it was an “uplifting” book for me, because what I remember about it is Joe making a place for himself and earning respect, even from people who had despised him. And Lulu using her skills to save people. And the two of them finding the right balance between what they both want and need out of life, so they can have a happy ending. It was suspenseful and sometimes painful, but that’s not what I took away from it.

I’m glad for that — I hope more people will give it a try! I noticed it doesn’t have a ton of Goodreads reviews, which made me sad, because it deserves to be read.

How have I missed this fine blog??

I hereby declare myself the hoary old Godmother of wonkomance. Anybody who thinks they’re older and tougher, prove it. ;)

As to the topic…yer thinkin’ too hard. It will give you writer’s block.

Ask me how I know.

You can be the hoary old Godmother of whatever you like, Laura! Though you might have to fight Theresa Weir for the title. Maybe she can have the contemporary belt, and you can have historicals.

Thanks for stopping by — hope to see you around often!

Wonderful discussion! I greatly enjoyed “His Very Own Girl” because of the emotions created by the setting as well as by the characters. Overall, because I love history so much, I see romantic hope in any setting due to getting to the heart of history–the people, via biographies, letters, memoirs–when I embark on research. The fact that a couple living in 1942 England or 1856 Russia or 1194 France are so different from my everyday life is escapism in and of itself. Plus, when I pick up a romance, anything can happen because I know there is a HEA, an emotional payoff in spite of the darkness of the setting at the end of the book.

That’s a great hope. And also, now I want more historical romance set in Russia. Can I have collective farm historical romance? Red Bread in romance form — that would delight me.

Terrific post, and fabulous conversation. I think threshhold and personal preference play an enormous role. I found Flowers from the Storm uplifting, not disturbing, and I don’t mind dwelling in a dark place if I know I’m headed for a genuinely redemptive experience. Like Ruthie, I am intrigued by the theoretically unredeemable element–the person, backstory, political position, or time period that “can’t” be redeemed–it’s an irresistible challenge. So I’ll always be drawn to reading and writing those books (though as a writer I might resist, out of a desire to have some mainstream apppeal).

I also loved Ruthie’s husband’s point about subjectivity and the “we.” I hadn’t given much thought to that before. Or–something else I was just thinking about–to the the fact that I identify with the nobility in Regencies even though I probably couldn’t have been that “we.”

I am always vaguely aware of the whitewashing in historicals–but then, most romance writers whitewash contemporary life, too, removing references to toileting, menstruation, illness, the true messiness of sex, etc. I’m sometimes irritated by the lack of realism but not half as irritated as I am when someone throws up in my romance.

No puking in romance. Serena’s hard-and-fast rule.

” I don’t mind dwelling in a dark place if I know I’m headed for a genuinely redemptive experience. ”

As I once famously commented (re “Fargo”) — “you have to go through the woodchipper to get to the redemption.”

I sympathize with this post quite a bit. I don’t want my fun books to depress me. I know one book that sits right on my personal “fun/not fun” line is PRIVATE ARRANGEMENTS by Sherry Thomas. SUCH a good book, but I turned the last page feeling sad, and sorry that the story unfolded the way it did.

I think I *would* read romance knowing that it would be heavy, or that I’d find the experience rather grim. But I’d want to have plenty of advance warning, so I read it at the right time, and in the right mood.

One thing I notice about historicals is that the way that soldier heroes are described. It’s become pretty common to read about soldier heroes who have PTSD, for example.

But I’ve never thought historical romances were primarily about investigating the conflicts of the era. They’re about the conflicts of today, examined an alternate setting.

I agree, re: historical romance being about conflicts of the day. I think that’s why I *can* read it — that I figured out it’s not history in book form, so I don’t have to read it as a historian. It’s also why I can’t bring myself to care all that much about inaccuracy in historical romance.

Oh, I want to read this book now! I had a similar feeling to Megan Hart’s Dirty. It was just so sad and the heroine was so damaged. I wasn’t sure the couple could overcome her issues. I think I called it “too real” for erotic romance. I like a bit of fantasy and escape and I’ve never understood why these things are looked down on. Let’s celebrate them, along with male nudity and tawdry sex scenes.

The irony is that MY books are on the real side. I’ve been called gritty, even bleak. My endings aren’t always happy for every character. I feel bad when a reader comes away with a sad feeling, because that isn’t my intention. As romance authors, I think we all (or most of us) struggle to find the right balance of angst and payoff. A certain amount of hardship makes for a satisfying HEA. Too much can result in a dark, heavy read. And of course one reader will feel uplifted by the same book that depresses another!

You should read it! It’s fascinating. And you’re right — we’re all so different, and our intentions can’t be mapped to our results. (Witness me sending you my light & frothy novella and making you weeeeep by accident.)

I thought about Dirty while reading Ruthie’s post as well. I loved how bleak it was.

It might be that erotica has more room for that kind of uncompromisingly grim perspective than romances do.

I loved the Lofty book. I also loved Connie Willis’ Nebula-winning Blackout and All Clear — the war in Britain affected the nation profoundly, and I just love books that get that right. I appreciate romance in a disturbing historical setting, such as this one, or Laura Lee Guhrke’s Conor’s Way (reconstruction south). My squeamishness kicks in when the individual characters’ situations are too awful, not so much the historical setting — I haven’t been able to finish either Flowers from the Storm or Seize the Fire, although some of Kinsale’s other books are among my very favorites in the genre. I think definitions of “escapism” vary, and what works for some readers clearly doesn’t work for others. I would say Robin’s right that we don’t all find the same thing “romantic,” but that doesn’t make it not Romance; and like Liz and Janine, I prefer the large umbrella for the genre, rather than narrower definitions. I’m not wedded to “hero” and “heroine,” either; if I enjoy the book and believe that the characters who end up together have earned it and will be happy, then I don’t really need “heroic” behavior from them. I like to see a couple work for their happiness, and to see that they are better, stronger people as a result of that work, but I prefer main characters with quirks and flaws that don’t necessarily go away at the end of the story.

Ooh, I’ll have to pick up that Guhrke! I just read my first book by her (And Then He Kissed Her) and was super impressed with it. And the Reconstruction South was such a horrid mess — should be interesting.

I’m with you on all these points, esp. “hero” and “heroine,” which are so limiting (but so inescapably tied to editorial expectations, if you’re writing on contract for a publishing house).

I will embrace my discomfort and the big umbrella. :-)

Pingback: Reading and Remembrance | Something More

Hello, I’m the editor who worked on HVOG with Carrie, and I just wanted to chime in to say that this thread rocks. “Escapism” is a difficult concept to parse, so I commend you for not shying away from the conversation; I agree that it’s all about threshold. The mindfulness you all applied to this discussion strengthened my resolve to champion the more challenging historicals (like HVOG) that I love. I hope I’m not overstepping, but you’ve gained another follower today for your fearless examination of expectations.

Welcome to Wonkomance, Kate! We could use some editors around here — we’re mostly writers and readers — and I’m happy that you chimed in. And if ever you have a wonky project you’d like to introduce to us, do drop us a line.

Pingback: Linkspam, 11/16/12 Edition — Radish Reviews