A friend recently read the manuscript of one of my not-yet-published books and emailed, “This isn’t a romance, it’s a manifesto!”

I smiled when I read that — but then paused, wondering why I was smiling. Had she meant me to smile? The email was only one sentence. Praise or critique? Was it a good thing, in fact, to have written a not-a-romance manifesto?

Possibly not, right?

Possibly not.

But what I wrote back a few minutes later was that all my romances are manifestoes — it’s just that sometimes, when the books are funny and cute, no one much notices.

What is a manifesto, after all, but a declaration of the author’s views? A manifesto presents an argument, marshaling all the author’s power of logic and emotion behind it. It’s a declaration of her life stance — her global philosophy made manifest, clear, and conspicuous.

Manifestoes have a reputation for stridency. They insist upon themselves. This is the right way, the only way, they shout. Listen to me! Change your life along these lines, or else!

I can’t help but feel, at first blush, like this sort of thing has no business in romance. These are pleasure books! That we read for fun! Take your manifesto politicking elsewhere, madam.

Speaking generally, manifesto-making isn’t often an activity of women. We’re encouraged so often, when we’re young, to get along, collaborate, contribute, soothe. This is one way, one option, we learn to suggest. You can take it or leave it. There’s some evidence for my view, I think? Here are a few citations. But it’s complicated. I’m just saying. Whatever you think.

When I think of manifestoes, I think of men. I think of Luther nailing his theses on the church door. I think of Marx and Stalin — humans so loud, so strident, that they had -isms named after them. I have never wished for an -ism to be named after me, but I do have views. I have opinions, arguments, and as I get older I’m starting to discover, too, that I have a life stance, a global philosophy that is mine-all-mine, and it comes out in my novels.

Is that bad? Is that … a problem?

I don’t think so. I think a novel kind of has to be a manifesto, of some kind. It has to create a world, and within that world it has to establish stakes and define the terms of happiness. A happy ending isn’t a happy ending in a vacuum, after all. It’s a happy ending for these characters because the novelist has told us what these characters need, why their needs matter, and what their happiness looks like.

So it only makes sense, if I am writing books about life and love, that I have to develop not simply convincing characters and situations — credible stakes for those characters, credible problems for them to overcome — but also a credible argument for what love means. What needs it fills. And, implicitly, what life is for.

That’s a big project. A big argument to be making in a little love book.

That’s a manifesto.

And I’ve noticed, since I started thinking about this, that the parts of my own novels that I usually like best are the parts that are most obviously manifesto parts — the passages where I am defining happiness, speaking to what love is all about, talking directly to the question of what we should live for.

In the manuscript that prompted the email, my very favorite part is pretty clearly a manifesto:

“Don’t get me wrong,” he says. “I like this. I want this. But shouldn’t we be talking?”

My hands are under his shirt. Sneaking up his back, his smooth tan skin, every bit of him familiar but different, broader, stronger, harder. “We are talking,” I say.

Because we are. What he means is that we’re not following a script.

Only, there is no script. There are no rules for this.

I don’t think we’re doing it wrong, because I don’t believe there’s any way to do it wrong or any way to do it right outside of how I feel, how he feels, how we feel between us.

All the songs are love songs. That’s what I’m learning.

All the songs are love songs, and this one is ours.

Here, the heroine is defining for herself what right and wrong mean in the context of her relationship. She’s defining the shape of her love, and in the process, her future. Her life.

But of course, she doesn’t exist.

I’m defining them. I’m defining them for you.

Which I think opens up some interesting questions, actually. First, the whole question of reader preference, reader desires, reader-to-author “fit.” Because we talk often about what readers want. Publishers spend a lot of time forecasting trends, trying to get the right contracts lined up so they’ll have the right books at the right times. But none of that activity, those contracts, addresses this deeper meaning, this core argument.

In romance, the author’s manifesto is, by and large, understood to be irrelevant to … well, kind of to everything.

My work isn’t contracted as manifesto. I don’t talk about manifesto in my synopses. Reviews rarely get into the arguments my novels make. But what does happen is that when readers aren’t convinced by my arguments, they don’t like my books. There is no way, perhaps, to like a book whose argument doesn’t work for you. And probably the essence of fit between readers and authors is a sort of receptiveness to argument, a match in love-politics, a compatibility in life-politics, broadly understood.

Second, I wonder about manifesto — about argument — in the context of conversations about romance and feminism, which sometimes get bogged down in questions of whether the genre as a whole can be understood as feminist, or if individual books can be feminist if they depend on an ending in which the heroine’s happiness is defined in terms of her being situated in a permanent, monogamous heterosexual relationship, and so on. Might it help to look more closely at how individual romance novels define love, life, happiness, self-worth?

Or possibly I have no idea what I’m talking about.

Anyway.

What do you guys think?

“Or possibly, I have no idea what I’m talking about.”

I’ve spent a good *cough* fifty *cough* years apologizing for my opinions. Both of them. Which change regularly, depending on who I’m with. I am the female, non-skeevy (I hope) Zelig of the Midwest. ( and here’s the IMDB link to Zelig, which is the only Woody Allen movie that I ever really ‘got': http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086637/?ref_=nv_sr_1 )

I’m getting better, though! At least I KNOW when I’m sitting on that fence, wobbling in my convictions.

And I’m pretty sure, usually, that I believe, very much so, that LOVE IS A GOOD THING. And we all need more of it.

So you go, girl…keep manifesting. Or whatever.

I will! Thanks, Teri.

I think it was Jane from Dear Author who I first heard talk about how romance novels each make a case, an argument. I think I remember her point being that how well a romance works for an individual reader depends on the how convincing that argument was to a reader, so unsatisfactory ending, resolutions out of left field where essentially bungled arguments, because the author failed to make the case for the romance. That case/argument of which Jane was referring I think is slightly different from the manifesto you are referring to. I know that I have been sucked in and even enjoyed books whose manifesto I rejected but whose romantic argument satisfied me. These are often compelling but problematic books for me. Their definitions of love, intimacy and happiness are not my own but ones I can believe the characters believed in.

All books have embedded worldviews but whether those manifestos are shallow or deep depends on the author. I’ve been one of those reviewers who has struggled with how not to derail review by discussing a fascinating element in a book’s manifesto that might have little to do with how the main romantic plot is resolved.

I certainly enjoy reading and tracking the manifestos in your books. I’ve already mentioned to you my interest how you depict faith and faith journeys in your books. And I know I highlight the heck out of manifesto statements in books as I read. They call to me and stick with me long after I have forgotten some character’s name or HEA.

“I know that I have been sucked in and even enjoyed books whose manifesto I rejected but whose romantic argument satisfied me. These are often compelling but problematic books for me. Their definitions of love, intimacy and happiness are not my own but ones I can believe the characters believed in.” — Right! It’s interesting to think about argument and manifesto as separate aspects of a novel that might work or not work for you as a reader in different ways. Makes for a very complicated matrix of reader enjoyment.

Interesting! Have to think for a bit. I’m thinking about whether manifestos have to be strident, whether romance can be successful if it IS strident, and whether we object to all stridency or only female stridency. Also about the distinction between the argument of the romance and the manifesto of the book, which Teri gets at–whether there is one, whether there should be one, etc. I’ll try to come back and dump my thoughts once they’re coherent …

These are super interesting questions, too — manifesto and its relationship to stridency, and then how we feel about stridency in our fiction, and why. I do think Ana gets at an argument/manifesto distinction that I agree with, although I suppose argument and manifesto work together and would be hard to completely tease apart.

I totally think you should have an -ism named after you, js. <3

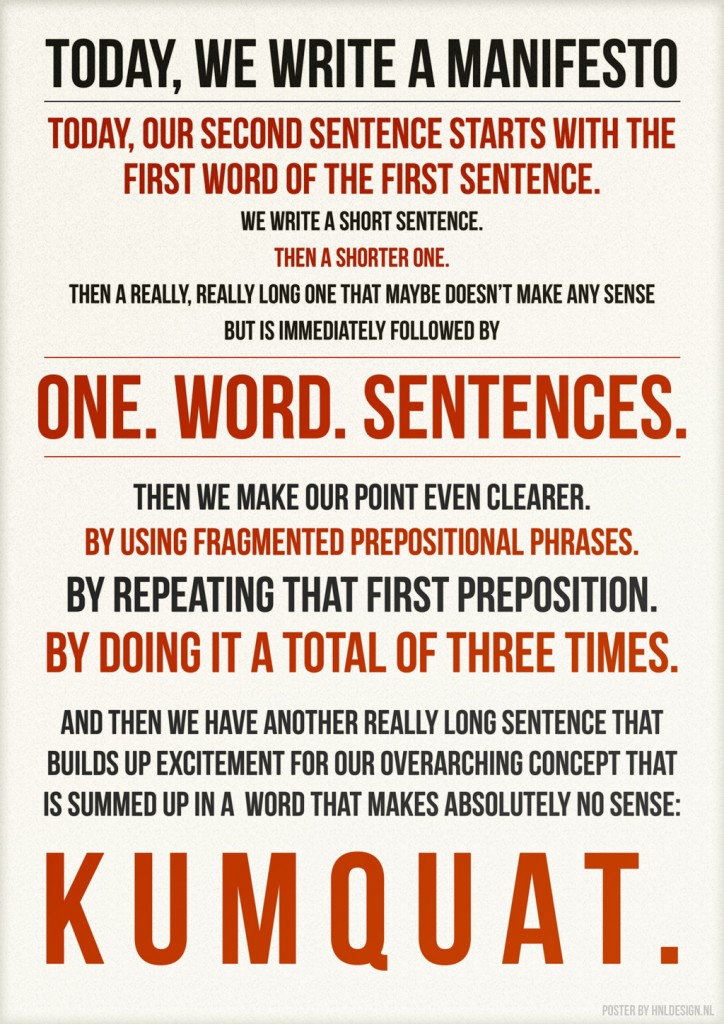

1st, that is an awesome graphic. It made me laugh hard. :)

Thinking about manifestos, I think my favorite books, the ones that I read over and over again (because I can reread a book TO DEATH), are the ones that definitely have manifestos. Although I guess I need to qualify that by saying that I like books that are written like yours, where the manifesto is fused so seamlessly into the story that it’s not as if I’m being beaten over the head with a brick. When I read characters who have realized something *true*, deep down, this is the most important thing I know, true, that’s what sticks for me and that is an author who’s managed to make their manifesto the core of their book.

As you all have said, the actual story arc may not be about this at all, but it’s the part that rings out most clearly to me & makes it clear that “this author is for me”.

For my own books, I think the idea of having a manifesto aligns closely with what I’m figuring out is my core story: people finding ways to take care of each other. Caretaking is my core story & I think my most recent ms. all have scenes that make it clear that this is what I see as important. This is my manifesto.

But I also think I need to think more about this. :)

Isn’t it great? It’s not mine — a found Internet thing. Should have credited it better!

And yes, I agree — no one wants to be beaten over the head with a manifesto. Or, at least, I don’t, as a reader. But I do like for the characters to work their way to truths that matter to them, and those truths are always going to be things I think are important, too, or else why write the book?

I think your graphic just explained away Hemingway’s style of writing! Did you get study him in college?

But yeah, what you said! That’s why I’m so particular about the romances I will read, and why I write what I do. I have a very definite world-view, and it comes through in my books. I didn’t set out to do that, but that’s how it’s worked. That’s what they refer to as an author’s “voice”. One of my BFFs from college says she feels like I’m sitting in the room talking to her, when she reads my books. That’s a good thing…I think.

Oh, it’s not mine! I need to write a credit on there. But it is an awesome graphic.

And yes, I read a little Hemingway in high school and college. Oy.

I’m not sure I think that voice and manifesto are the same. I think of voice as having more to do with tone, word choice, approach to a subject — the sound and feel of the writing, rather than the content?

What I like about writing romance today is that you can tweak and play with traditional constructs if you want e.g. have transgressive femininity welcomed and rewarded instead of punished, or play with non-traditional meanings, viewpoints and interpretations of love etc. There certainly seems to be a broader range of ‘manifestos’ acceptable in romance these days.

I think it’s true that there’s a lot of room for different manifestos these days. Although, if you look back at the explosion of category romance in the 1980s and 90s, there was a lot of room then, too! Just for different sorts of things, maybe.

I often wonder why I prefer certain people or books over other people or books. Why do I choose one over the other. I think maybe there is something deep inside us that recognises kindred spirits who share parts of our ‘manifestos’ with us. This sharing creates the link.

I think this is true — and that we can recognize these kindred spirits quickly, and that the kindred-ness carries across all their books, which we will enjoy more or less but always enjoy, because that essential connection to manifesto, worldview, is always there.

Feeling all kindredy now Ruthie :D

I do agree that no novel is neutral. All of them are manifestos in the sense that all of them transmit certain ideology. And certainly, we women should be more proactive, express ourselves clearly, defend what we believe in.

The writer’s ideas are always in the book, but they should appear in the tropes he/she chooses, in the way the characters behave or think or what they say. I don’t think we readers want to see directly what the author thinks.

So I would say something is a manifesto in a bad sense – when suddenly the story & the characters are gone from the book and the only thing that remains on the page are the author’s ideas. The risk? Well, if the reader does not share your ideas, he/she can loose his/her interest. And it could easily be a DNF book.

That is true, that if the manifesto doesn’t come out of the characters, out of what are genuinely true-to-character insights and feelings, it’s probably poor writing. But also that an author’s manifesto might alienate a reader even if it’s done well, because we’re all so different, and value different things.

Pingback: Stumbling Over Chaos :: Insert your own linkity title here

Pingback: LoveSexLoveSexLoveSexLove | Wonk-o-Mance