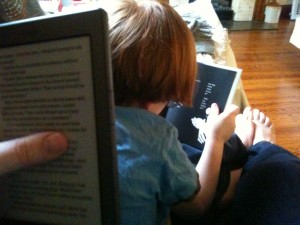

I recently complicated my own kid’s love affair with books, and I’m not even a little sorry, in fact, it’s worse, because I knowingly led him to a book hangover so wretched, he refused to speak to me for nearly an entire day, and he’s six. Speaking is what he does.

This kid is one who gets in trouble over books and over reading at school, such is the intensity of his limerence, so you can appreciate the full icy bloodlessness of my crime. I received a note home from his teacher, for example, telling me that it was discovered that he had hoarded more than thirty classroom books inside of his desk.

“You could not possibly have read these,” his teacher reportedly sad.

“I’ve read all of them, except this one,” and he showed her a book with a bookmark still in it, and then gave her an accurate summary of all the rest of the books.

“But when?” She asked. Because, after all, he’s at school where they presumably do school stuff, which is something more than sitting in a bean bag for hours at a time reading, which is what he does at home. “When did you read all of these books?”

“Always,” was his answer. “I am always reading them.”

I can tell already that this business with the school desk book hoarding will be apocryphal, as will the general battle between him and his second grade teacher over his preference to read over all other presented curriculum. I hope it is apocryphal because his eco-steam fantamance has settled into its 300th week on the bestseller’s list, not because he is still taking second grade.

On the occasion of my knifing, we were having a nice weekend, mostly reading together between breaks to eat sandwiches and make tea. He’s been reading independently for a long time, but does enjoy being read to, and I was feeling motherly and expansive, so I thought it would be nice to pick out a book for just that. We’d had a conversation earlier that day about dramatic tension and emotional conflict, which he can be a little wary of. The Cressina Cowell books he’s reading now, the roughly seven hundred books in the How to Train Your Dragon series, involve a good deal of father-son conflict, both interior and exterior, and he reads it with one hand over his eye in order to race to the dragony parts or the kissing parts.

Our conversation about emotional conflict was a good one actually, we were able to identify that his discomfort comes from what it is that sees the characters should feel, or that he wishes them to feel, as the reader, and their actual action or feelings presented by the narrative. More directly, for example, Hiccup’s father should be proud of him, because Hiccup is exceedingly smart and creative, but his father lectures and berates him, instead, for his curiosity and lack of physical strength, both of which task resources for the rest of the community. This conflict is impossible for my kid to accept because it exists because we know what is the right thing for Hiccup’s father to do and yet, he does not do it. We cannot make him do it, either, because he is bound to a static and permanent narrative. We are, as readers, at the mercy of this conflict. We are held hostage by it. Which is, of course, why as more sophisticated readers, if we feel that a book’s conflict isn’t “good” we’re disappointed.

actually, we were able to identify that his discomfort comes from what it is that sees the characters should feel, or that he wishes them to feel, as the reader, and their actual action or feelings presented by the narrative. More directly, for example, Hiccup’s father should be proud of him, because Hiccup is exceedingly smart and creative, but his father lectures and berates him, instead, for his curiosity and lack of physical strength, both of which task resources for the rest of the community. This conflict is impossible for my kid to accept because it exists because we know what is the right thing for Hiccup’s father to do and yet, he does not do it. We cannot make him do it, either, because he is bound to a static and permanent narrative. We are, as readers, at the mercy of this conflict. We are held hostage by it. Which is, of course, why as more sophisticated readers, if we feel that a book’s conflict isn’t “good” we’re disappointed.

Because, really, unmerciful dramatic tension that grabs us by the shorthairs and won’t let us look away is delicious. But it is delicious in exactly the way we mean something that is an acquired taste is delicious. Coffee, beer, and dramatic emotional tension are not for six year olds. If you’re six, you want juice and the kissing parts, all the way, embroidered with pratfalls and straight narrative action of the flying dragon variety.

So when we had this discussion, we also talked about how emotional tension is crafted by the author to make us, the reader, feel things. Because he is lucky, and has a dad that loves him as he is, Cowell is able to reach him with the conflict in the narrative I described and make him feel uncomfortable, frustrated, even angry. Narrative pits the lived experiences of humanity against artifice, against a narrative written one way for innumerable readers. And you know, he got that; saw the magic in it. Saw how, if he was a kid who’d had Hiccup’s experience with his own father that the same passages might make him feel sad, instead of indignant. It was a kind of Reader Response 101, and a lesson that demonstrated the equal power of both the author and the reader, how the relationship between the two is a dynamic way for one story to be a number of stories. It’s one of those ideas that is complex in its simplicity, like many of the best things we learn as children.

So while I had initially thought I’d pull down the first Harry Potter to read, given our conversation, I reached for Sharon Creech’s Love That Dog, instead.

Those of you who know this book have a handle on where this is going.

Now, we had just talked about how emotional tension is a craft, and there is a way in which, already, I was a little bit unpacking and demystifying the magic of books. A little bit. Maybe not at all, depending on your perspective. Some of us see the magic in taking a thing apart and putting it back together, after all, and some of us prefer to just enjoy what is that has been made. We had gotten to this idea that the author makes choices, makes choices based on the author’s understanding, as a human, about how human’s behave and how best to show that behavior to the reader in such a way that the reader finds themselves bringing their own human experiences with humans to bear on the text.

Now, we had just talked about how emotional tension is a craft, and there is a way in which, already, I was a little bit unpacking and demystifying the magic of books. A little bit. Maybe not at all, depending on your perspective. Some of us see the magic in taking a thing apart and putting it back together, after all, and some of us prefer to just enjoy what is that has been made. We had gotten to this idea that the author makes choices, makes choices based on the author’s understanding, as a human, about how human’s behave and how best to show that behavior to the reader in such a way that the reader finds themselves bringing their own human experiences with humans to bear on the text.

On his own, he had pointed out that Cowell didn’t have to say, didn’t have to write, that Hiccup was hurt, my kid just knew he was because Hiccup cared so much about his own experiences, and his dad, who he loved, did not. While my kid was working on that, then, all I had to do is ask my kid what it was he thought Hiccup wanted, which he very easily was able to say that he wanted his dad to be proud of him, and then I pointed out that this wasn’t anything that was actually written down, that it was his own emotions in conflict with the actions of the text that came to that conclusion, and by then my kid was pointing out a zillion other examples of dramatic and emotional tension and conflict in the text with that delight, which I’ve mentioned, of figuring out a simple complex idea.

So, I said, this is how books make us laugh, as well, or also, make us cry. The books don’t tell us to be uncomfortable, or angry, or amused, or sad, we tell ourselves to be, or really, we get in touch with things we have already felt before, by reading about familiar emotions in unfamiliar settings and getting the opportunity to safely feel those emotions without risking a new experience.

I pulled out Creech, actually, not because I wanted to break apart my kid into little pieces, but because he asked, could a book make us feel something we had never felt before? In other words, could we have a novel emotional experience by engaging with enough familiar human narrative action in the text that we learned a new feeling?

What would it feel like, is what he asked, to feel something I never felt before because I read it in a book?

Love That Dog is technically a middle grade book, though it is really one of those life books that is for everyone. It is a book told in a series of poems written first, under duress and the direction of the narrator’s classroom teacher, and then with joy as the narrator Jack discovers that he is a poet.

It is also a book about a little boy engaged with the unspeakable grief of losing his first best friend, his dog Sky, in a terrible and confusing hit and run accident. What’s more, Jack’s healing comes not only from his burgeoning love of writing poems, but from his nurturing his very first author obsession with the real life poet Walter Dean Myers, who makes a fictional guest appearance in Creech’s book.

The book starts out at the shallow end, wading us into what will be excruciating emotional tension established by Jack’s refusal to write about his beloved dog because it hurts too much, and the reader’s awareness that he should, oh Jack, you really should, even as the grief hurts us as well. This small start is simply one of Jack’s very funny and reluctant school-assignment poems after another, many of which are in direct conversation with his teacher. My kid delighted in these, no stranger to conflict with his teacher himself, and yet, even before my kid really knew what it was that Jack was avoiding, he picked up on the fact that Jack was avoiding something, and that it was big.

Wait, my kid stopped me at one point, just before the drop into the abyss, what is Jack hiding?

Oh, darling boy. Only his whole entire world.

So here, in a eighty-six page book with maybe a hundred words on every page, it is revealed to my son that yes,

you can feel all kinds of things you’ve never felt before, deeply, painfully, incisively, even if you have never lived them. You can feel not only the grief of a small boy who witnessed the death of his own animal, but more complicatedly, you can feel what it is to bury that grief and what it is to be small with a grief that is unresolved and festering. What’s more, when that seems too much, too unbearable, you can feel what it is for the wounds to come open and come clean, and to find your joy, the joy that heals you and excites and most of all, allows you to write your masterwork, a poem called “Love That Dog,” and what it might be like if your favorite poet in the world read your poem, and visited your class because he liked it so much.

My kid felt all that, and so no; he couldn’t speak. Not to me, not to anyone. He entered that space between himself and a book, a space that hadn’t previously existed and now was undeniable. He’d walked alongside a narrator he identified with who compared my son’s life with his own and demonstrated the difference so sharply that the difference no longer mattered, only what they had in common, which by the end of the book, was almost everything.

The result, since, is a kind of dear and bittersweet caution, on his part, with which he approaches a new book. How he reads the back copy, and looks at the cover, and asks what its about. How he reaches for a familiar book to reread after reading a new one, and how he criticizes an author’s choice, sometimes, in how he or she showed him something new.

And how he carefully has avoided a certain book that drew the line between before and after, as if the book is a live thing, not so static, that might dare to show him something else, about himself, that he never knew.

Oh, Mary Ann, you make my heart bleed (in a good way) reading this post. It’s so beautiful. It’s so thoughtful. It’s so deep and wonderful.

This is such a beautiful description – “He entered that space between himself and a book”.

I love your kid and your relationship with him. Thank you for this exquisite post. I hope books always bring him joy, learning and heart ache at their beauty.

Cate xo

This is a wonderful wish for my kid, and I thank you.

He is a great kid, his complicated relationships with second grade notwithstanding.

xoxo

Somehow the ways books break us seems to me a bigger tragedy than the way life does. Probably because I spend too much time in my own brain. I had similar lessons taught to me by books, though when I was much older, and I didn’t have a parent or teacher to guide me. After reading this post, I can’t decide if I’m more sad for your son, the dog-bereft boy, or myself.

You know, it was a complicated afternoon, in many ways.

There are so many good reasons to cry in life that I don’t, but I will cry even over small moments in a book. It’s another reason I need books.

This is a beautiful post thank you. Touched me deeply. Entered into the three sided relationship between my son, books and me.

That’s a beautiful relationship, and it makes its own kind of space, too.

What a lovely post this is. There is something amazing, isn’t there, about being able to have these conversations with small boys where you can dig into the things that they love, and give them *more* of those things? And they get it. They always get it.

I think the books that wreck us this way are so memorable, and sometimes being read them out loud makes them even more so. I was never quite the same again after hearing my third-grade teacher read us STONE FOX.

I remember the intensity of deep understanding that came from listening to Mrs Sundgren read TALES OF A FOURTH GRADE NOTHING — the marriage of humor and tears in the same book — how that worked, why they were both so important in the same space.

Rivers. Rivers.

Rivers of tears.

The sweet, it hurts.

What Cate said. And how much more powerful that you were there with him where I imagine lots of kids have to go it alone without understanding the wilderness or the magic. And thinking a screen based game is more fun.

We got plain old lucky with the screen game thing because his uncle makes apps and games and stuff and so he gets that the very first thing that happens is that a story has to be *written.* The game part is how that story is told. He’s not uninterested in writing stories that are told that way, but it was a revelation for us, as parents, too — to give us a way to talk about screen games, and to use the same kinds of questions we would with books, and it get our kid questioning them and approaching them critically.

And you know, some stories are pretty straight-forward. Fruit Ninja, for example; it’s hard to pin the trope down on slicing a mango to bits with a sword.

GORGEOUS post. brava.

setting iCal date in 2033 to search for eco-steam fantamance, i am, yrs,

–m

I think it will be a thing. Ecologically powered devices in fantasy worlds with kissing. I am pro!

Thank you xo

When my oldest was six, he went to story time at the library and asked if they had any books about arm farts.

Did they? Because mine is incredibly frustrated he can’t figure out this skill and would love to find some good nonfiction recs that breaks it down.

It’s a beautiful thing, though, when they make that connection between what they want in the world, and that he can be had at the library or in books. Like this unquestioning faith that if it’s arm farts they want, the library is all “oh, we’ve GOT this.”

LOL, I don’t think they did. It was a small branch library…but I bet that library lady never forgot him!

Dan’s 20 now, but I bet if he were to have occasion to connect with your son, he could give him some arm fart lessons. It’s certainly a skill I never mastered. Must be a guy thing.

Lovely, lovely post. You took me back to when I first read a book that broke me (I was about your son’s age). It’s truly a life changing moment. (And I hoarded books in school as well, and, given a choice, always preferred reading over other subjects. The balloons on my first grade reading clown? I kept turning in so many book reports that my teacher asked the question your son’s teacher asked. My mother’s assured her that, yes, I really had read all of those.)

Love That Dog was one of those books for my younger daughter too. It still has a place on her bookshelf and in her heart all these years later next to The Book Thief and The Perks of Being a Wallflower and Harry Potter and Emily Dickenson, books that ripped her apart and put her back together again into someone new and different.

(i just did a big book purge [six boxes for housing works thrift shop, one for each daughter’s school, one for the synagogue library, go me] and i could not bear to get rid of Love That Dog! it is all that and a bag of kitten chow.)

Wow! You brought me to tears with your post! Thanks.

You reminded me of how joyous it was to be the mom of my 4 kids, helping them to realize things like this. We read every night to them, and when new books would come out they all wanted to read, I’d read to the whole family, husband included, around the campfire. It was truly family time. I lament about not being able to find a full-time job in any field, after having been p/t for so long, while they were young. But I treasure memories like these.

When my boys loved “The Plant That Ate Dirty Socks” and all of the sequels, that starred two brothers who shared a room with a plant that cleaned up after them by chomping on the smelliest of socks, they used to think up new ideas for the next book. I helped them write to the author, and SHE WROTE BACK! They were beyond excited! She thanked them for their ideas and complimented them on their creativity!

And as an English teacher, they never had a choice of whether or not they’d like to read. The whole family reads.

Thank you for sharing. Loved the post, the analysis of the reading process, the love evident that you and your son have for one another and how books and their stories and discussion can provide a common bond. Loved every pay of this entry and would hope that every teacher would read it and implement the parts of it in their regular instruction. Thanks for sharing a piece of yourself and family with your readers.

Thanks, Mary Ann, for this lovely, lovely post. It reminds me of when I was reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s LITTLE HOUSE IN THE BIG WOODS to my daughter. At first, she said she liked Laura the best, but when Laura got into trouble (my daughter HATED to get into trouble!), she decided Mary was the character she liked the most. Then, ofter the one time Mary got chastised, my daughter changed her mind again. “I like Ma the best.”

I’ll bet now, though, now that a few years have passed, and that she’s grown a bit of a tougher skin (from life, and from reading books), that she could appreciate Laura a bit more…