Ruthie here — just a quick introduction to Amy Jo Cousins, a Friend of Wonk. We asked AJ to write this guest post for us after she shared an earlier version of these reflections with a number of the Wonksters. I’m delighted to be able to get her thoughts into the wider world, because I think what she has to say here about community and being a romance writer in the digital age is both important and interesting.

Take it away, AJ!

————

A while back, Cara interviewed the Wonkomancers about scarcity in Romancelandia, right around the time I had a long weekend writing retreat with a group of romance authors. Between that post, that weekend, and how Thanksgiving sort of rocked my world this year, I’ve been thinking about gratitude and plenty, about generosity and community.

When my first two books were published, almost a decade ago now, it was the most alone thing I had ever done. I knew exactly no one who had written a book. Although my family and friends were thrilled for me and supportive (bought me red boots and threw me surprise parties and let me dance in the open sun roof of the limo zooming down Lake Shore Drive), they had no advice or information about the process.

It wasn’t yet RT. I know this because I still have the two copies I bought at a B.Dalton Bookseller.

I talked to my editor a handful of times on the phone and I went to one regional conference, where I met her in person and we had about ten minutes of conversation. At that conference, I talked to a lot of very nice people, but didn’t make any connections that lasted beyond an email or two. That was mostly my fault, I think. I assumed that any published author would see my reaching out to them as an imposition on their time. The unpublished authors were even shyer than I was.

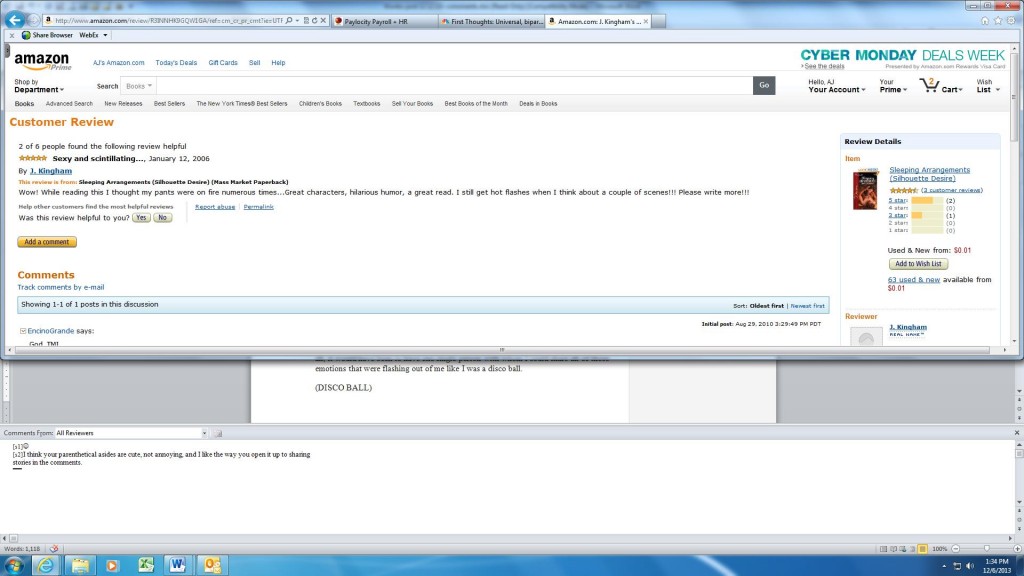

When my books came out, they were reviewed in Romantic Times Magazine, but that was pretty much it.

Smart Bitches, Trashy Books started later that year. None of the dozens of book review websites existed. Goodreads didn’t exist, which is hard to imagine. I cobbled together a shitty website using HTML for Dummies and, wonder of wonders, four or five people found it and emailed me. I threw a party for each book that was mostly an excuse for my friends and family to get a drink & my romance novel for free if they donated a children’s book to the elementary school on Chicago’s West Side where I volunteered. I didn’t see any sales numbers until I got my royalty statements the following year. Amazon existed, but no one I knew bought books there. One of my brother’s friends posted a goofy review about how my book set his pants on fire.

The entire publication process felt like I tied parachutes made of Kleenex to my books and dropped them off a cliff into a bank of clouds that swallowed them whole. I hoped they landed okay. It was awesome and awe-inducing. It was the thing I’d dreamed about since I was a little girl sitting at a tv tray table in a corner of our damp basement (because the clatter of my used electric typewriter at midnight kept everyone awake.) I was giddy with excitement. I was also crushingly, heart-breakingly alone. I had no idea what the fuck I was doing most of the time (scratch that…ALL of the time), pretty sure that I was always two seconds and a coin toss away from making the mistake that would have Harlequin writing me off as Too Stupid To Live. If I could have wished for anything at all, it would have been to have one single person with whom I could share all of those emotions that were flashing out of me like I was a disco ball.

The entire publication process felt like I tied parachutes made of Kleenex to my books and dropped them off a cliff into a bank of clouds that swallowed them whole. I hoped they landed okay. It was awesome and awe-inducing. It was the thing I’d dreamed about since I was a little girl sitting at a tv tray table in a corner of our damp basement (because the clatter of my used electric typewriter at midnight kept everyone awake.) I was giddy with excitement. I was also crushingly, heart-breakingly alone. I had no idea what the fuck I was doing most of the time (scratch that…ALL of the time), pretty sure that I was always two seconds and a coin toss away from making the mistake that would have Harlequin writing me off as Too Stupid To Live. If I could have wished for anything at all, it would have been to have one single person with whom I could share all of those emotions that were flashing out of me like I was a disco ball.

Any time a friend or co-worker mentioned wanting to write a book some day, I went into overdrive. “Have you read Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones? Want to do NaNoWriMo with me? We can meet at coffee shops and write together! Please, please, please write a book!” I was desperate to know people who weren’t just writing in journals and thinking about a book (as I had done for the first thirty years of my life…hush, I was too thinking about being a writer from the moment they pulled me out with the forceps and smacked my butt), but were actively engaged in this magical and perplexing publishing thing.

So *clears throat* when I say that these past six months have been just the teensiest bit like someone took every birthday / first star in the evening sky / penny in the fountain wish I ever made and somehow managed to make them come true, I am maybe approaching a description of how overwhelmingly different my experience has been this time around.

From the brand new Twitter friend who I’d met once IRL before she took me under her wing at RWA and introduced me to everyone she knew, including authors around whom I was twitchy and mute with hero worship (I’m getting over this, I swear), to the members of a Chicago M/M Romance reading group who keep inviting me to meetings even though I can hardly ever make it…

From the writers “across the pond” with whom I talk about WWII research texts, to the group from Down Under who hosted a contest that introduced me to new editors…

From the #1k1hr sprinters on Twitter who keep me producing, to the Tumblrs who make me blush and inspire me…

You people have beta read my manuscripts and provided feedback both wise and geographic (“I think you mean either the Back Bay or North End of Boston. There is no Back End neighborhood…”). I boggle at the hours of time you gave up to do this. You have let me sit in on the equivalent of a Master Class in publishing, listening to stories of book deals gone wrong, cover art disasters, agents who tear down their authors and agents who build them up. You have mailed me cookies and made me Korean food and bought me drinks and turned my tweets into memes. You have shared your family’s Thanksgiving sweet potato recipe and emailed me your books before they were released when I was sad because our cat died. You have fixed my plots and punched up my synopses and found me the perfect cover art images. I am awed and overwhelmed and I never, ever feel alone in this journey any more.

*pause for eye-wiping and sniffing*

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Talk about a living, breathing repudiation of the idea that there is any scarcity at all in Romancelandia. You are wonderful people and I am so, so grateful to sit at your feet, metaphorically. Or dance on them, sadly less metaphorically.

Sometimes we don’t celebrate enough how generous and kind and helpful this community is. But I wanna share the love. Got any stories of awesomeness?

————

Amy Jo Cousins lives in Chicago, where she writes contemporary romance, tweets more than she ought, and sometimes runs way too far. She loves her boy and the Cubs, who taught her that being awesome doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with winning.

Find her on Twitter @_ajcousins.