I was at dinner last week with a couple of writer friends, and one of them jogged my memory about something I’d said a long while back. Such a long while back, in fact, I can’t recall if it was a blog post—and if so, where—or a comment on someone else’s post, or what. In any case, it was something I’d written on the importance of hero imperfection. I believe I’d mentioned three metrics: handsome, successful, well-adjusted. I’d posited that in order for a hero to be both appealing and also have enough flaws to allow room for a satisfying character arc, he could be two of those three things, but not all of them. Or he could be a bit of each—decent-looking, reasonably sane, and not destitute. I wanted to revisit this idea again with a bit more focus, and the method I’ve come up with I’m calling the 28/40 Method.

When I was in junior high, I repeatedly attempted to play Dungeons & Dragons. I didn’t have the patience for the rules, but I loved creating new characters. I remember you got to roll a six-sided die three times each for different traits—strength, agility, charisma, intelligence and…um… Some other things. The way my brother taught me to play, you rolled a bunch of times, then you could distribute the totals as you wished. You might wind up with a really smart, fast character who isn’t very strong, or a dumb-but-charismatic hulk. This was very exciting to me, and I want to steal its essence for this post.

When I was in junior high, I repeatedly attempted to play Dungeons & Dragons. I didn’t have the patience for the rules, but I loved creating new characters. I remember you got to roll a six-sided die three times each for different traits—strength, agility, charisma, intelligence and…um… Some other things. The way my brother taught me to play, you rolled a bunch of times, then you could distribute the totals as you wished. You might wind up with a really smart, fast character who isn’t very strong, or a dumb-but-charismatic hulk. This was very exciting to me, and I want to steal its essence for this post.

For the 28/40 Method, your hero is possessed of four different traits. At the start of the book, for each trait, he lands somewhere on a scale of 1 to 10…

Attractive. Whether he’s got a devastating face and fantastic dress sense, or a shaved head, mean mug and a killer body, we’re talking raw good looks, whatever flavor they might come in. Scoring a 10 on this scale would equal the most gorgeous man the heroine’s ever seen; a 0 would be straight-up fugly.

Talented. This could mean an actual artistic talent, incredible business sense, athletic prowess, or exceptional intelligence; whatever gifts might make a hero stand out as something special. A 10 could be an Olympic gold medalist, artistic genius, or a rocket scientist; a 0 would be a very dull man with no hobbies or interests.

Rich. Inherited from a wealthy family or the spoils of an empire built up from nothing, we’re talking money money money, or some other tangible measure of material success. A 10 might be a billionaire or a prince; a 0 would be a homeless guy.

Balanced. Mentally, that is. This refers to the hero’s reasonableness, emotional intelligence, empathy, mental health, chemical dependence, temperament, and so forth. A 10 would be kind, thoughtful, ethical, rational and patient; a 0 might be a sociopathic addict with anger management issues.

The last thing you want is a guy who scores a perfect 10 on all of these traits. That’s the Superman Syndrome—a guy so perfect he actually loses all his dynamism. Yawn. And yeah, I know about Kryptonite and everything, but come on. Superman’s got WAY too much going for him. We like underdogs. We like struggle, and success that comes only to those willing to fight for it. And you want your hero to have room to improve over the course of the book, so starting from perfection equals a static non-arc. That’s not just boring for readers, but unsatisfying.

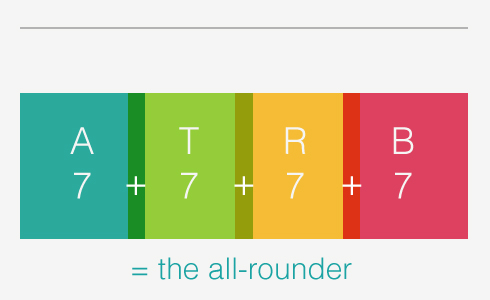

Using the 28/40 Method, you get 28 points to create your hero at the start of his book, and you can spend up to 10 points on each trait. That means your hero could conceivably be perfect at two traits, but lousy at the other two. 28 is a maximum cap, to keep him from being too perfect, but 28 is also a minimum cap, because in fiction it’s important for a character to be a touch exceptional—he should be worth having a book written about him! Here are some options.

A = Attractive | T = Talented | R = Rich | B = Balanced The All-Rounder is above-average at everything, but doesn’t truly shine in any way. Okay-looking, competent, stable, nice. He’d make a good single-father character or maybe a small-business owner, a man whose priority is stability and who strives simply to do right by those who rely on him. Nothing wrong with that—but not all that exciting either, in my opinion.

The All-Rounder is above-average at everything, but doesn’t truly shine in any way. Okay-looking, competent, stable, nice. He’d make a good single-father character or maybe a small-business owner, a man whose priority is stability and who strives simply to do right by those who rely on him. Nothing wrong with that—but not all that exciting either, in my opinion.

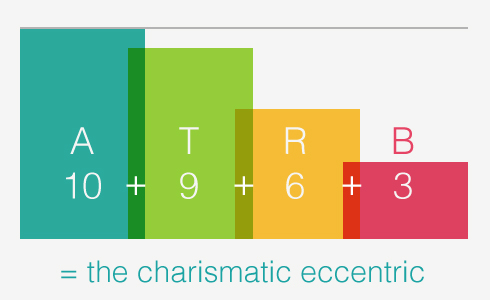

The Charismatic Eccentric—I wrote his guy! Didier Pedra, the gorgeous French prostitute from the Curio books who’s insanely good at sex and cooking and clock repair, but not especially wealthy and also a complete mental wreck (despite being emotionally fluent.) This might be the kind of man you look at and think, “If he’s that ridiculously beautiful, he’s bound to be an idiot, a psycho, or a basketcase.”

The Charismatic Eccentric—I wrote his guy! Didier Pedra, the gorgeous French prostitute from the Curio books who’s insanely good at sex and cooking and clock repair, but not especially wealthy and also a complete mental wreck (despite being emotionally fluent.) This might be the kind of man you look at and think, “If he’s that ridiculously beautiful, he’s bound to be an idiot, a psycho, or a basketcase.”

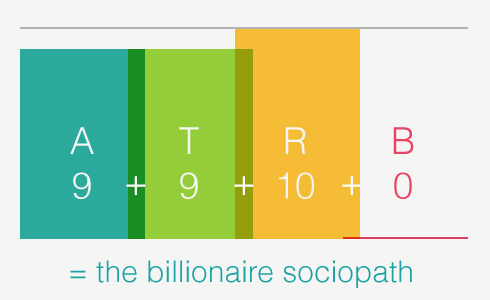

The stunning Billionaire Sociopath. I don’t think I need to explain this one.

The stunning Billionaire Sociopath. I don’t think I need to explain this one.

The Struggling Star. Crazy-talented and determined, aching to get to the top. Think nascent rock star, broke-but-hungry prize fighter, genius toiling in his basement lab.

The Struggling Star. Crazy-talented and determined, aching to get to the top. Think nascent rock star, broke-but-hungry prize fighter, genius toiling in his basement lab.

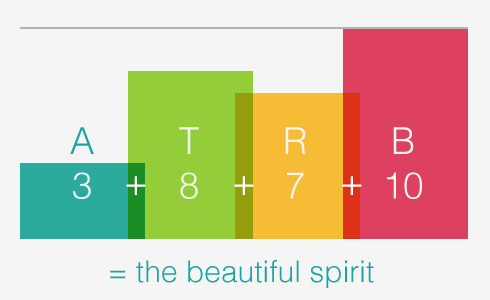

The Beautiful Spirit. AKA that guy Charlotte ends up with on Sex and the City. A not-so-stunning hero is a rare creature in Romancelandia, but they must exist! A talented writer can turn a guy with below-average looks into a stunner, if they know how to let his intelligence and kindness and other assets shine through the plain brown-paper packaging.

The Beautiful Spirit. AKA that guy Charlotte ends up with on Sex and the City. A not-so-stunning hero is a rare creature in Romancelandia, but they must exist! A talented writer can turn a guy with below-average looks into a stunner, if they know how to let his intelligence and kindness and other assets shine through the plain brown-paper packaging.

So those are just a few examples. By the end of his book, the hero’s still not going to add up to 40, but he will have made some strides. Arguably, the most important trait to improve on in the run-up to the happily-ever-after is Balanced. After all, a self-respecting heroine can fall for a homely man, a man without much unique talent, a low-earning man. But she really shouldn’t ride off into the sunset with a guy who’s still a 2 on the well-adjusted scale—we’d worry about that woman, hitching her wagon to an addict or a manipulator or an icicle or a hot head. Luckily this is also the trait that tends to improve naturally in romance, as the hero adjusts his attitude and behaviors and priorities, to become worthy of the heroine.

Hope this proves a useful lens for any writer folks out there, busy formulating the next crop of romance heroes! I’d love to chat in the comments if anyone has questions, insights, issues, or sees this formula reflected in any favorite heroes that they’ve written or read.