I’m pleased to welcome Alexis Hall back with another guest post — this time one for the “Formative Wonk” files. I love this essay on reading and identity, and what we find when we’re young, seeking reflections of ourselves in literature.

———

It was pretty much decided I was queer from a young age, though queer wasn’t the word they used. It’s the word I use now because it’s the one that troubles me least, the one that evades definition, as I wish to do as much today as I did all those years ago. Back then I really had no idea what any of this meant, only that I was different in some way, not quite right, not quite what was wanted. In that world my queerness was as much my quietness, my cleverness, as it was any burgeoning sense I might have had about my sexuality. In that world, in the eyes of those around me, those things were inextricable. So I read. Looking for the mirror that would reflect my strangeness that I might begin to understand it.

The first I found was Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, though I read it too young. I don’t know how it had come to be filed in the children’s library. I think, perhaps, someone had mistaken it for worthy, stodgy children’s history, which was why it nestled there in its dull brown cover between Rosemary Sutcliff and Roger Lancelyn Green, this bold, difficult, love story, narrated by Alexander the Great’s Persian eunuch, Bagoas, who a few lines of Plutarch suggest may have been his lover. It’s a fascinating book, a powerful and a poignant one, bluntly unapologetic in its depiction of homosexual love. To this day, The Persian Boy remains one my favourite books, reached for as instinctively as a partner’s hand in moments of distress or uncertainty. Now, I can see now Renault’s consummate skill, her effortless fusing of history and fiction, and the way she imbues such distant, inaccessible figures with the necessary emotional authenticity to make them real. How she shows us the pride of a eunuch, the strength of a courtesan, the person at the heart of a phenomenon, tenderness in war, and the peculiar seductiveness of Alexander’s conquest. It’s not a balanced love, perhaps not even a healthy one, for Bagoas’s devotion to Alexander’s greatness is not, and cannot be, reciprocal. But at the same time what they have, what they share, is undeniable. Powerful. Unquestioning and unquestioned.

The first I found was Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, though I read it too young. I don’t know how it had come to be filed in the children’s library. I think, perhaps, someone had mistaken it for worthy, stodgy children’s history, which was why it nestled there in its dull brown cover between Rosemary Sutcliff and Roger Lancelyn Green, this bold, difficult, love story, narrated by Alexander the Great’s Persian eunuch, Bagoas, who a few lines of Plutarch suggest may have been his lover. It’s a fascinating book, a powerful and a poignant one, bluntly unapologetic in its depiction of homosexual love. To this day, The Persian Boy remains one my favourite books, reached for as instinctively as a partner’s hand in moments of distress or uncertainty. Now, I can see now Renault’s consummate skill, her effortless fusing of history and fiction, and the way she imbues such distant, inaccessible figures with the necessary emotional authenticity to make them real. How she shows us the pride of a eunuch, the strength of a courtesan, the person at the heart of a phenomenon, tenderness in war, and the peculiar seductiveness of Alexander’s conquest. It’s not a balanced love, perhaps not even a healthy one, for Bagoas’s devotion to Alexander’s greatness is not, and cannot be, reciprocal. But at the same time what they have, what they share, is undeniable. Powerful. Unquestioning and unquestioned.

And when I first read it, I had no idea what was going on at all. I only knew that I was Bagoas’s age, that he suffered, and was ashamed, that he was different, in the way others perceived him and treated him, and that he survived. Bagoas is a difficult narrator, not always sympathetic, certainly far from reliable, driven to love Alexander initially as much by his own pride than anything you might call romantic: “And I said to myself, looking after him as he walked away, I will have him, if I die for it.” But I admired him so, for that pride, and I knew I wanted whatever it was he got. I had no notion what it was two men might do together, but it seemed like it was something worth having: “My body echoed like a harp-string after the note. The pleasure had been had piercing as the pain used to be before.” And, because my understanding was so limited, because these ideas seemed at once so abstract and so familiar, I didn’t think to wonder that one man might seek such things in another. Or that they could be found there.

And that was my first reflection: a Persian boy. I see him sometimes still.

The next came some years later. After The Persian Boy, I had found only misery, lovers doomed to betray each other or be torn apart by a world that could not accept them. Sometimes they murdered or raped each other, or got decapitated. I had just about come to the conclusion I would be more likely to find love as a Persian eunuch (I knew what this actually entailed by now, which will tell you just how unlikely my prospects of future happiness seemed to me right then) when I read Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man. Isherwood, I would later discover, was as frustrated as my younger self with what he termed the myth of the tragic homosexual, though on the surface his novel about a grieving, alienated middle aged gay man would seem to support, rather than contradict, this myth. Except, no. A Single Man is a book about life, not death, and grief is merely the mirror through which it shows us love. It’s a remarkably effective device – since Isherwood could not portray the reality of the love between two men, he depicts instead the reality of its loss. Just as a personal aside, this aspect of A Single Man resonates for me with The Persian Boy, or rather with a line from Funeral Games, the next novel in the series. Bagoas is only incidentally present in this book, but by far the most striking reference is this one, at Alexander’s funeral:

The next came some years later. After The Persian Boy, I had found only misery, lovers doomed to betray each other or be torn apart by a world that could not accept them. Sometimes they murdered or raped each other, or got decapitated. I had just about come to the conclusion I would be more likely to find love as a Persian eunuch (I knew what this actually entailed by now, which will tell you just how unlikely my prospects of future happiness seemed to me right then) when I read Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man. Isherwood, I would later discover, was as frustrated as my younger self with what he termed the myth of the tragic homosexual, though on the surface his novel about a grieving, alienated middle aged gay man would seem to support, rather than contradict, this myth. Except, no. A Single Man is a book about life, not death, and grief is merely the mirror through which it shows us love. It’s a remarkably effective device – since Isherwood could not portray the reality of the love between two men, he depicts instead the reality of its loss. Just as a personal aside, this aspect of A Single Man resonates for me with The Persian Boy, or rather with a line from Funeral Games, the next novel in the series. Bagoas is only incidentally present in this book, but by far the most striking reference is this one, at Alexander’s funeral:

[Ptolemy] had come remembering the elegant, epicene favourite; devoted certainly, he had not doubted that, but still, a frivolity, the plaything of two kings’ leisure. He had not foreseen this profound and private grief in its priestlike austerity.

That line never fails to move me. But, beyond the pain, there is a terrible sort of triumph, I think, at the heart of grief. To grieve is to love, to have loved, to love still. To live, and to be human, to be the same. The deepest cruelty of A Single Man is not that George has lost his lover, but that he is denied the space to grieve him. Like George himself, A Single Man is sometimes an angry book, a lonely and a bitter one, but it is also beautiful, hopeful and even celebratory. George is fifty eight when the novel opens; his partner, Jim, has been dead for about a year. These are not tragic homosexuals – they are people who have shared a lifetime, a banal, beautiful, perfectly recognisable lifetime, full of everyday, familiar, real love:

What is left out of the picture is Jim, lying opposite him at the other end of the couch, also reading; the two of them absorbed in their books yet so completely aware of each other’s presence.

The novel follows a single day in George’s life. He goes through his routines at home and at work, thinks of Jim, talks to his colleagues, teaches, meets up with a friend, embarks upon an anti-flirtation with one of his students, and it ends him with in bed, masturbating unrepentantly (and apparently quite satisfyingly) over the memory of two young tennis players he saw earlier in the day. Or rather it ends with the novelist asking us to suppose – he emphasises merely suppose – that George dies of a heart attack that very night as imminent demise is, of course, the only socially acceptable fate for the irredeemable homosexual. But this is little more than a piece of artifice. Because A Single Man is ultimately about love, the end of love, and the life that continues after.

So that was my second reflection: a grieving fifty eight year old. If he is my future, it is not so terrible.

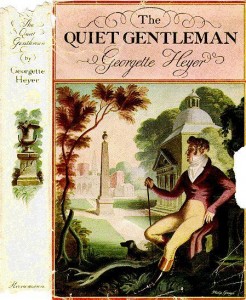

Then I found Georgette Heyer. But AJH, I hear you say, there’s nothing queer about Georgette Heyer. And maybe you’re right, but identification is more complicated, and more fluid, than the literalities of personal similarity. Or, to put it another way, queer is in the eye of beholder. Especially when the beholder is, you know, desperate. My grandmother had a box of Heyers in the attic, and I still remember those little books so vividly: their flaky yellow-brown dust jackets, and the scent of stale air rising from the pages. I read them all, every single one, but you always remember your first. Mine was The Quiet Gentleman, one of Heyer’s rather disregarded works, I think. The hero, Gervase Frant, the Earl of St Erth, returns to his deceased father’s estate to claim his inheritance, only to discover his family aren’t mad keen on the notion. Cue mystery, intrigue, attempted murder, & etc. The atmosphere is rather gothic, at odd variance with the deep thread of anti-romanticism that runs through the whole novel. It is, in essence, the love story of two deeply sensible people who find themselves caught in a maelstrom of drama and silliness. It’s not zingy or lively like some of Heyer’s other novels, but it’s adult and oddly satisfying. Also, both Gervase and his eventual romantic interest, Miss Morville, are slightly out-of-step with their worlds, and the people around them; they have each cultivated their own resistances. Miss Morville wields her placidity like a weapon and Gervase… oh Gervase:

Then I found Georgette Heyer. But AJH, I hear you say, there’s nothing queer about Georgette Heyer. And maybe you’re right, but identification is more complicated, and more fluid, than the literalities of personal similarity. Or, to put it another way, queer is in the eye of beholder. Especially when the beholder is, you know, desperate. My grandmother had a box of Heyers in the attic, and I still remember those little books so vividly: their flaky yellow-brown dust jackets, and the scent of stale air rising from the pages. I read them all, every single one, but you always remember your first. Mine was The Quiet Gentleman, one of Heyer’s rather disregarded works, I think. The hero, Gervase Frant, the Earl of St Erth, returns to his deceased father’s estate to claim his inheritance, only to discover his family aren’t mad keen on the notion. Cue mystery, intrigue, attempted murder, & etc. The atmosphere is rather gothic, at odd variance with the deep thread of anti-romanticism that runs through the whole novel. It is, in essence, the love story of two deeply sensible people who find themselves caught in a maelstrom of drama and silliness. It’s not zingy or lively like some of Heyer’s other novels, but it’s adult and oddly satisfying. Also, both Gervase and his eventual romantic interest, Miss Morville, are slightly out-of-step with their worlds, and the people around them; they have each cultivated their own resistances. Miss Morville wields her placidity like a weapon and Gervase… oh Gervase:

All that could at first be seen of the seventh Earl was a classic profile, under the brim of a high-crowned beaver; a pair of gleaming Hessians, and a drab coat of many capes and graceful folds, which enveloped him from chin to ankle. His voice was heard: a soft voice, saying to the butler: “Thank you! Yes, I remember you very well: you are Abney. And you, I think, must be my steward. Perran, is it not? I am very glad to see you again.”

Here we have a man whose first on-page acts are to look awesome and be polite. And he continues to look awesome and be polite for basically an entire book, but yet there’s no suggestion that it makes him weak, unmanly, or unattractive. On the contrary, he’s presented as the sort of person an intelligent, interesting woman might want to fall in love with. It’s all so obvious, looking back, but Gervase was my first inkling that masculinity need not be this brute, blunt thing I was told I lacked. It was the first time I really began to question what was inherent and what was constructed. And to see the vast chasm between who I was and who I was supposed to be, not as some deep, irredeemable wrongness in myself but a simple mismatch between what I wanted and what was wanted of me.

Which is where we leave my younger self, I think, with this third reflection. The one that looks neither backwards nor forwards but shows most simply who I have spent my life trying to be: a quiet gentleman.