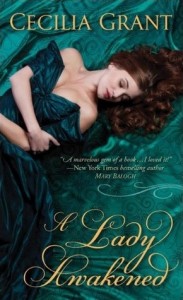

I read Cecilia Grant’s A Lady Awakened in a trance, a state not unlike swimming through the deepest layers of a dream. I rarely reach that layer of involvement in my reading—not in “literary” and not in romance—and it’s the highest compliment I can give a book. I grabbed it whenever I could get my hands on it and finished in two deliciously wonky nights.

I read Cecilia Grant’s A Lady Awakened in a trance, a state not unlike swimming through the deepest layers of a dream. I rarely reach that layer of involvement in my reading—not in “literary” and not in romance—and it’s the highest compliment I can give a book. I grabbed it whenever I could get my hands on it and finished in two deliciously wonky nights.

Here’s the story:

Martha Russell’s husband has just died, and, because she’s heirless, his estate will go to her brother-in-law. Unless, of course, she should happen to be pregnant with an heir.

Martha knows she’s not pregnant, but instead of telling her solicitor the truth, she tells him she needs a month to find out for sure. And then she hires her neighbor, Theophilus Mirkwood, to impregnate her.

Theo has been exiled by his father from London for womanizing and otherwise wasting time and resources. He’s supposed to be behaving himself on his country estate, not dallying with widows. But he’s a sucker for Martha’s beauty and agrees to the plan.

The problem is that Martha is only interested in Theo’s semen-delivering properties. She despises sex and refuses to allow herself to enjoy it at all. But she is deeply determined to make her scheme work, especially after she discovers that her brother-in-law took advantage of the female servants when he lived on the estate. Much joyless sex ensues, until Theo can barely bring himself to do his studly work.

And then—spoiler alert—slowly but surely, Grant leads us to happily ever after.

There are some very conventional aspects to this book, on the surface. The premise—widow must involve herself in unconventional sex/love/marriage situation to hold onto her property (usually for the good of the servants or the tenants) is familiar to readers of Mary Balogh’s Slightly Married and many other historicals. Theo is not a particularly unusual hero. He’s rakish and handsome and knows it, and until the heroine pushes him to be a better man, he’s not the deepest well on the estate.

There are also some profoundly wonky bits. Martha’s iciness during sex goes far beyond the blushing virgin trope. She hates the sex, she hates the idea of the sex, and she doesn’t want to ever like it. And her dislike of Theo goes beyond her distaste for the sex. She has no respect for him at all. And rapidly—as you might imagine—he develops matching feelings for her.

But this isn’t a classic I-hate-you-I-want-to-bonk-you setup. The disconnect between hero and heroine grows, not shrinks, during the first half of the book; it endures much longer than is typical; and there is no steamy hate-bonking to compensate for that cold core to the book. The sex is decidedly, brilliantly, unsexy.

She put her knees apart and closed her eyes. Vague noises ensued: he must be readying his male parts, as he’d done yesterday. A moment later, it began.

Martha gave a small sigh, just to herself. This again. Presumably this was enjoyable with a man one desired. Absent desire, she was left only with the weight of another body on hers. Strange skin against her own, with hair in strange places. Hip-bones pressing into her, and everything pressing into her. Seeking entry; seeking and … gaining it, there, on one long slide.

Can we talk about the brilliance of that scene? “Vague noises,” “readying his male parts,” “it began,” “strange skin,” “hair in strange places.” If she had referred to grunts or moans or groans or sighs, we would have been turned on. If she had said his cock, his dick, even his penis, our conditioning would have taken over. But she exploits the way our snake brains recognize what’s sexy. She keeps us suspended and unfulfilled, just like Martha. Until that very end sentence, when she gives us just a little hint, just enough of a hint—that “there” in italics capturing that unwanted pique in interest on Martha’s part, and the long slide driving it home. Note the tension Grant is holding us in—the sex is awful, but you keep believing it doesn’t have to be. There. One long slide.

I couldn’t put it down.

I argued a couple of months ago that truly wonky books tend to provoke love/hate reactions, and this book is no exception. Some readers hated this book. They hated that Martha committed fraud, that she’s cold, snobby, and unresponsive, that the hero is shallow and conceited. They wanted to know why the hell Theo didn’t move on when Martha proved herself to be not only sexless but also narrow-minded and judgmental. They felt—many of them even said so explicitly—that Grant had violated their expectations about what romance should be. “This is not a bad book,” wrote one Amazon reviewer, “simply this is not the type of story I look for in a romance.”

By contrast, this is exactly the type of story I look for in a romance. For nearly the entire time I was reading it, I was transfixed by what was passing between this opposites-attract couple. I couldn’t believe either of them was sticking it out—and yet I completely believed it. I believed it because it was so evident to me that both the hero and heroine desperately needed exactly what the other one had to offer. They just didn’t know it yet.

I’ve referred before to what Michael Hauge says about why people fall in love in the best love stories. He says that too often, the halves of the couple come together for little or no reason. If you ask the author why the man loves the woman and vice versa, the author shrugs and says, Who can say what draws one person to another? Or—Hauge’s favorite answer—Chemistry!

But Hauge says that the real answer in a well-crafted love story is that the hero and heroine can see about each other what no one else can see. They can see past all the defenses and down to the real self.

Martha and Theo are not the classic romance hero and heroine—two thoroughly likable, popular, sunny people who happen to have minor flaws that have kept them from committing. Their wounds, their individual forms of self-loathing, in this case, have infected not just their love lives but everything about them. Theo thinks so little of himself that he can’t take anything or anyone seriously; Martha’s fear of opening up makes her take everything and everyone too seriously. They could go on like that forever, but deep in their psyches, they don’t want to. They want to be saved, fixed, reborn.

Of course it is not easy for them to like or want each other. They are nothing alike. And yet—of course it is inevitable that they will come to need and love each other—they are perfectly aligned to bring each other to life. Long before they know it intellectually, they “see” it in each other in the way Michael Hauge means. They sense it there, deeper than conscious knowledge. And Grant manages to convince us of both things at once–both that they cannot connect and that they know at a deep level that they must connect.

That tension—the same tension Grant employed so brilliantly in writing the sex scenes—the push of what they think they want and the pull of what they need—is what drew me in and kept me deep. That and Grant’s phenomenal storytelling and gorgeous writing.

It’s hard to balance depth of damage and likability. Most romance heroines are not the Grant kind, whose troubledness infects every inch of her. They are the popular, sunny, minor-flaw kind. We’re tolerant of wounded heroes because the downsides of a wound—the inability to connect across the board—are more socially acceptable in men than women. But we want our heroines mostly okay. I thought Grant’s gamble, her willingness to push that envelope, succeeded fabulously, but that’s the danger of walking the wonkoboundary. Not everyone will see it that way.