There have been only a handful of times in my life where I’ve wished I were more educated. If there’s something I don’t know, I can research it and find the answer—I live in a university town, and I have the Internet at my fingertips at all times. There is very little beyond my reach, in terms of gathering information.

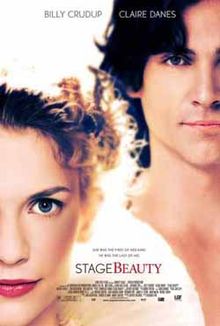

But when I sat down to watch the movie Stage Beauty (2004), a longtime favorite of mine, with the intention of studying it solely for character in terms of sexual identity, I was astounded. What I found could fill a master’s thesis on the subtextual elements of body dysmorphia, gender identification, and sexual fluidity of male actresses in 17th-century London…and damn, I wish I had reason to write it. Unfortunately, there’s no call for sweeping academic essays from undergrad-educated nobodies, and this blog, no matter how lovely its readership, is the wrong platform for my fascinated (yet not very fascinating, I know) ramblings.

I will not be able to do it justice, so I will instead just tell y’all about how freakin’ awesome this movie is. For realz.

Stage Beauty is a sexual-fluidity-in-conflict social statement masquerading as a costume drama masquerading as gender-equality politico film. It is a love story between a man and himself and the woman who bravely-but-not-blindly worships him. It is heart-wrenching, gut-punching look at self-identification in turmoil, with moments of heartbreaking truth and painful fallacy brought to life by a handful of the most talented actors on whom the movie industry could lay its greedy hands.

Stage Beauty is a sexual-fluidity-in-conflict social statement masquerading as a costume drama masquerading as gender-equality politico film. It is a love story between a man and himself and the woman who bravely-but-not-blindly worships him. It is heart-wrenching, gut-punching look at self-identification in turmoil, with moments of heartbreaking truth and painful fallacy brought to life by a handful of the most talented actors on whom the movie industry could lay its greedy hands.

Plot summary: During Charles II’s reign over England in the 1600s, only men could be actors. Edward “Ned” Kynaston was the most beautiful woman of the London stage, but when his dresser, Maria, makes a splash by breaking the law and performing the role of Shakespeare’s Desdemona, the wheels of social change begin to turn. Charles II decrees women—and only women—can perform the female roles. Ned is suddenly out of work; but more than that, he’s completely lost his identity, having been trained to play only women on stage since his youth. As Maria’s fame grows, Ned’s own life turns sordid. An upcoming performance of “Othello,” to be attended by Charles II, necessitates Maria and Ned work together—him as her tutor, and she as his savior.

Ned (played by Billy Crudup) is a visually stunning man. He isn’t overly tall, and in the many scenes where he is only wearing underclothes, the viewer can see there isn’t an ounce of spare flesh on his lean, muscled frame. He isn’t feminine, nor is he androgynous, but he is beautiful, and much of that beauty is in the way Crudup portrays Ned—utterly certain in who he is, thus breeding a misplaced and eventually maladroit confidence when that certainty crumbles.

It’s an ugly crumble, too, when Ned falls apart, but Crudup does it splendidly. Painfully, but splendidly. At the same time, we see Maria (Claire Danes) rise with no little hesitation from her idol’s ashes. She never wanted to destroy him, but in order to do what she loves—act—Ned, as he is at the beginning of the movie, cannot exist. And before my most recent viewing of the film, this was my big take-away from it, what I thought was its most powerful message.

I wasn’t wrong, but I wasn’t correct, either. While these two couldn’t live in the same role in the same world, because of their genders and sudden political and social changes, it’s more that Ned could not live in that role in that world because he had never been allowed to develop a chance to understand his gender for himself, or even his own sexual preferences.

Spoilers ahead:

We are told he was taken in by his former acting master, who gave a home to “pretty boys” from the gutter. This master taught them to read, tutored them in great dramatic works, and showed these boys the “tricks and turns” of femininity. The viewer can infer that these boys were sexually abused by the acting master, likely at an early pubescent age (10 to 15, I’d guess), and therefore shaped. Ned, quoting the former master, says, “Never forget, you’re a man in woman’s form.” He pauses, looking at Maria. “Or was it the other way around?”

Ned’s sexuality is, initially, confusing for the audience, much in the way that Ned himself would be confused, should he ever have pondered it. Dressed in drag, he maintains his “actress” persona on a carriage ride with two high-born ladies, who are trying to settle a wager as to whether or not Ned possesses the proper genitalia for his gender.

“Both of us were wondering if you were…well…really a gentleman. My father’s a wigmaker, he says you’re much too beautiful to be a gentleman. He says you must be a woman.” The second woman pipes in with, “And my mother’s good friend, the Earl of Lauderdale, says if you’re a man, you don’t have a gentleman’s thingy. He says you’re like those Italian singers—what was it?” “Castrati,” answers the first woman in a matter-of-fact tone. “The earl says they cut off your, uh, castrati, and you become a woman.”

Finally, Ned interjects, with girlish flirtation, “I take it the Earl of Lauderdale is not a surgeon.”

“No…he’s an earl.”

Ned plays with his fan, batting his eyelashes. It is obvious he is humoring them, but he’s getting quite a bit of enjoyment out of this situation, as well. “Well, how then may we prove to your father, and your mother’s…special friend…that I do indeed have a thingy?” He grasps their hands, slides them under the hem of his costume’s skirts. “A big, bulging, orb-and-scepter of a thingy.”

They are breathless as their hands are led inexorably toward his groin. “Well…I think we’d have to…uh…” “We’d have to touch it.”

“Touch what?” asks Ned, right as the women find him and turn rapturous. He pushes their heads down and makes his first very male noise, a low, pleased-sounding growl.

Later that night, after he returns to “shed his skin,” as he terms it, Ned enters the empty stage and begins to go through a series of very feminine-looking moves and gestures. Up to this point, when we’ve seen him walk, he moves lightly, gracefully; when he talks, it is at varying higher registers (with one notable exception, which I won’t spoil); and when he gesticulates, it’s as if his hands and arms are moving through water, leading with his wrists and flourishing with his fingers. He is effeminate without being a stereotype.

Waiting for him on that stage, however, is his male lover, the Duke of Buckingham. It is an incredibly unequal relationship, but what is most interesting about it is not that the duke rebuffs the little caressing, affectionate gestures with which Ned attempts to gift the more dominant man, but the duke’s insistence that Ned wear a wig. “Do you ask your lady whores to wear a wig to bed?” Ned asks playfully. “If it made them more a woman,” is the duke’s reply.

So then we are left wondering if Ned is gay. Or is he bisexual? Does he even know, himself? On the surface, it seems he gets off on being adored…with the exception of Maria. They have a camaraderie, conspiratorial but not easy, because she is soul-wreckingly in love with him, and he is oblivious to it. There is one early instance where she is lying atop Ned and he makes a move as if to kiss her, his expression curious, as if he’s realizing it’s the most natural impulse in the world but he doesn’t quite know why he’s experiencing it. But she pulls away, and later, when she sees him on the darkened stage with the duke, Danes makes her character’s heartbreak palpable.

The film continues, the plot evolves, and things happen. One such thing is Ned being beaten half to death by cohorts of the two women from the carriage, the term “bum boy” and “mocking your betters” thrown around beneath the voice-over of Charles II’s public announcement that only women shall play female roles on-stage from now on. If it were a modern setting, the simplest means of reading that scene would be as a hate crime, or gay-bashing. Again, it’s not wrong, but it’s not right, either.

Six weeks go by, and Ned is not completely recovered. There are still welts on his face, and he walks with a cane and a limp. He breathes differently. He speaks differently. There is a gravitas to him that is born of the terrible event he suffered but begins to bleed into his once-beautiful, once-practiced mannerisms. He approaches Maria, who hurts at the sight of him, and a mutual friend tries to encourage Ned to return to the stage in men’s roles—because Ned is actually an amazing actor, not just a beautiful woman when in drag: “Your performance of the man stuff seemed so right, so true. I suppose I felt it was the most real in the play.”

“You know why the man stuff seemed so real? It’s because I’m pretending. You see a man through the mirror of a woman through the mirror of a man. Take one of those reflecting glasses away, and it doesn’t work. Man only works because you see him in contrast to the woman he is. If you saw him without the her who lives inside, he wouldn’t seem a man at all.”

It’s then that we see how fucked up he is. His acting tutor did a number on him, and Ned is, maybe, only just realizing it himself. Or maybe he doesn’t realize it all; but Maria does. Maria knows. Throughout the entire film, she is the rock, the one unchanging thing, even though she is the catalyst for change. She never wavers, not really, in her adoration of Ned, and that enduring solidity (and solidarity) is what, eventually, heals some of the fissures within him even as it creates more. There is a wonderful moment where he looks at her with shock and a sort of breath-stealing recognition, and that moment returns later, again and again in different guises, during the last forty-five minutes or so of the movie.

He meets again with the Duke of Buckingham, asking why the duke didn’t visit when he knew Ned was hurt. Like before, Ned attempts playfulness, affection, but Buckingham will have none of it, and tells Ned he’s getting married. Ned is hurt, but it’s more confusion than pain. Another crack in his weakened identity. “What is she like in bed? What is she like to kiss?” The duke cuts him off with a roar, “I don’t want you! What you are now.” He struggles to control himself. “When I did…spend time with you…I always thought of you as a woman. When we were in bed, it was always in a bed on stage. I’d think, ‘Here I am, in a play, inside Desdemona. Cleopatra. Poor Ophelia.’ You’re none of them now. I don’t know who you are.” His look is pitying. “I doubt you do.”

Ned’s behavior decays along with his broken self-assurance. He drinks to excess, and it’s alluded to that he beds a few (or a hundred) female whores. He winds up in drag on a bawdy-house stage, drunk and showing his junk for a pittance when Maria finds him. She sobers him up in a small cottage somewhere just outside London, and it’s there that Ned seems to have his biggest breakthrough.

“What do men do?” Maria asks him.

“With women?”

“With men.”

“They, uh, we…well, it depends.”

“On?”

“On who’s the man, and who’s the woman.”

“I said men with men.”

“Yes, yes, I know, but with men and women there’s a man and there’s a woman, and it’s been my experience that it’s the same with men and men.”

“Were you the man or the woman?”

“I was the woman!”

“That means…”

He pauses. Smiles. It’s a dawning realization. “Riiiiiiight.”

Their banter, while conspiratorial as it had been in the early part of the film, carries far more flirtation—and far more awkwardness for Ned, as he is rather startlingly aware of Maria now—than it ever did. They kiss (oh, man, what a kiss), and he touches her face and neck using the feminine gestures he’d been taught. She mimics them, up until the point where he experimentally caresses her earlobe, and there’s a visceral shift inside him that the viewer can sense: He’s finally touching her as a man. He ends up on top of her, holding her head and her throat while he nibbles and licks at her, all teeth and lips and strong, splayed fingers, and it is very, very obvious that Ned is in charge. Ned is dominant.

It’s a new thing, for Ned. So it’s probably unsurprising that he messes it up in pretty short order.

The end of the movie features Ned and Maria on stage for Desdemona’s death scene, with Ned as Othello, first in rehearsal and then in performance*. He’s been walking, talking, moving in a far more male fashion than ever before. He’s bossy, authoritative, and alpha, but while it fits him, it’s apparent that he is still struggling with the concept on an intellectual and emotional level. He admits, in the final moments, that he still doesn’t know who he is, as he and Maria are holding each other (after another had-to-fan-myself kiss), but there is hope, an HFN that could very easily lead to an HEA.

There isn’t much discussion of want or need in terms of sexual desire and romantic interest in the film. The hero and the heroine are very alone in their individual desperation, and when they come together, there is incendiary chemistry. But the HFN/HEA? Not the point of the movie; or, at least, it wasn’t the point for me, this last time around. This time, I wanted to explore whatever was organic in terms of attraction for Ned; I wanted to know which gender of partner he enjoyed more; I wanted to know if there was anything special about Maria, or nothing at all, that had him revealing all those domineering teases.

Mostly, I wanted to know if Ned would ever get his definitive answer, because I felt like he needed one. Maria didn’t care what he was, so long as he was hers. But for Ned, a man whose life, up until a few months earlier, had been directed and stark and ever-so-certain, learning to live with a half-formed identity and a sexual fluidity that may or may not have been what his body actually wanted would be constantly terrifying. The audience can see that trepidation, in the end, and there’s nothing we can do about.

I still wish I could write that essay. I would research the heck out of the world’s libraries for a thesis like that. In fact, I had to cut myself off from writing more here. But the most important thing you should take away from this post is that if you haven’t seen Stage Beauty, you need to rent it, and if you have…maybe you should watch it again.

Because it is freakin’ awesome. And obviously very wonky. For realz.

*From a theatrical standpoint, Danes and Crudup’s death scene is one of the most brilliant Shakespearean performances I’ve ever seen. It makes my chest all funny and tight. You don’t even have to like Shakespeare to be shaken and awed by it, I promise. Just…feeeelings. So many feelings.

Ooh! *grabby hands*

It’s a top-five-of-all-time flick for me. Cannot even express how much watching it with a different goal in mind cemented that status. Billy Crudup is brilliant, just brilliant, and the chemistry between him and Claire Danes is absolutely volatile. I hope you get a chance to watch it, Del!

I’m being a pain, but… Here. $6.99, and it’s yours forever and ever, amen. :P

Pingback: STAGE BEAUTY: A Mini-Thesis (over on Wonkomance!) | Edie's Blog

Love this movie and yes, Crudup and Danes are amazing. (Rupert Everett was also a hoot as Charles II.) I thought it had a happy ending for Ned, because he’d found himself again as an artist. The loss of his artistry seemed as devastating, if not more so, than the loss of his sexual identity.

Of course, this makes me want to go watch it again…

I agree with you that the loss of his ability to perform as he wished to was devastating (Charles has the line to the effect of, “Exile is a terrible thing for those who know their rightful place.”), and Ned does say, when Maria asks why he didn’t finish her off, “I finally got the death scene right.” Which, like you mentioned, implies that he’d figured out he was where he was supposed to be when he’s onstage — in the men’s roles. (And if not where he’s supposed to be, at least where he CAN be, you know? He learns he doesn’t have to leave the theatre world entirely.)

I had always seen SB as having an HEA before, but when I went back recently and watched again — with an express purpose in mind — I was actually rather delighted with how ambiguous everything is for Ned while still giving the appearance of a happy ending. This movie has several instances of spectacular artistry, and it’s too bad it’s such an unknown entity, in the grand scheme of Hollywood-esque things.

Thanks for reading/commenting, Katy! I’m glad to find another SB-lover, like me. Enjoy watching the film again. :)

I have to re-watch, but going from memory, I can’t help wondering if Ned hasn’t stumbled across and made his peace with Keats’ negative capability:

He had certainty and it was comfortable and safe, but now I think he has something more. Or at least that’s the story I tell myself as I try to find the same peace :)

Oh, that’s a fantastic hypothesis. I like that quite a bit. Go, Keats. :)

Wow, adding this to my #1 spot on Netflix…. I know what you mean about wishing you had an academic outlet for some ideas. I’ve had a few of them and have told others “this should be a paper, someone should do this” :)

You could have gone on more and I would still have read it all. I can have a short attention span too when it comes to blog posts. I’ve been known to skim. But I read every word of this.

I hope you enjoy SB, Angela–it’s one of those movies that, I think, you gain enjoyment upon the rewatching of it. Plus, it’s about theatre. And history. Like crack for me, really. ;)

Thank you for your kind words!

Wow, what an amazing essay. This sounds like a fabulous movie. Will have to check it out, though I’m sure it will break my heart. Now go write the novel version. Go. I’m waiting.

I have a feeling this would not qualify under your Husbo’s “happy movie” rule. :P There are feelings. And conflict. And a plethora of drag queens, a la 17th-century London. Plus: Rupert Everett, Hugh Bonneville, Tom Wilkinson, Richard Griffiths…and Zoe Tapper (as the king’s blowsy mistress), who’s one of those British actresses I just love.

(P.S. I linked to the Amazon Instant page under Del’s comment. Aaaaaaand go.)

Yes, could never watch this one with Husbo. Too disturbing for him.

If you can get your hands on the play the film is based on, you’ll find yourself very happy, indeed.

I did read the playscript in college, actually! I was on a bit of an obsessive bender over the movie, and a theatre professor had a copy lying around his office. I wish I could see it performed, but I fear no man would compare to Billy Crudup’s Kynaston portrayal. :) Thanks for the rec, Jenni!

Edie, thank you so much for turning me on to this movie– as I noted above, I put it on my Netflix queue, and it arrived and I just finished watching it. Incredible movie. I literally sat forward–on the edge of my freaking seat-I’m not kidding–for that final death scene. Tears in my eyes. Overwhelmed. Just Phenomenal. I have to own this movie.

Thank you.

Oh, you are very welcome! I’m so glad you enjoyed it. It’s one of those films that just kind of socks you in the gut, isn’t it? :)