So this happens all the time. Somebody here posts something, and either the post or the comments get me thinking.

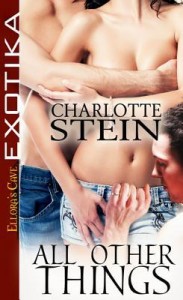

In this case the post was Ruthie Knox’s Aim for the Middle (Oh, and Also, There Is No Middle). In the comments, Sherri Porter and Sarah Wynde were discussing shame and enthusiasm, because shame is all about rule violation and Ruthie wrote, “I think enthusiasm kind of crowds out rules, so there’s no room left for them.” This is why the Romantic Times convention is the happiest place on earth, by the way. Sarah mentioned the Id Vortex, which immediately made me think of Charlotte Stein’s deliciously filthy book, All Other Things. Charlotte is for some reason inextricably linked in my mind with Michael Fassbender—I don’t know why, I don’t question it. So then I had to go watch Shame because it seemed the thing to do. Then somebody on twitter mentioned Brené Brown (thank you Doren Cassale and/or Megan Mulry), who did two amazing TED talks on shame and vulnerability. And at some point in that whole round of shame-related research, I read the original Id Vortex post again and really started thinking about how shame can be delicious and maybe even transcendent, and that whole stream of consciousness is a perfect example of why I love this blog.

Okay, lemme back up.

The Id Vortex is this great concept used by fan writer Ellen Fremedon to describe what so much fan fiction is about—tapping into all that stuff that, when we read it in a fic, ruins our childhood memories in the worst/best possible way. Stuff that’s obviously compelling, universal material, despite the fact that we all agree it’s horribly wrong (she used the term in the context of a Star Trek Mirror Universe/M*A*S*H crossover slashfic involving slavery, and you can use your own id to imagine specifics). In fan fic, Ellen Fremedon suggests, “we’ve all got this agreement to just suspend shame.” We know we’re not writing or reading it for literary merit, in fact we know it’s often deliberate wank fodder, so the usual rules of professional fiction vis-à-vis sex and social norms and other taboos don’t apply. We dive right into the good stuff, smashing fandoms together, hopping genres with abandon, shipping and slashing improbable and sometimes even illegal couples, subjecting familiar characters to all manner of outlandish lewdness, just because we find it hot and/or entertaining. She goes on to ponder “what the effect on, if not mainstream literary fiction, at least on mainstream genre fiction is going to be, when the number of fanwriters taking that toolbox with them into pro writing reaches critical mass—which I think it’s going to, in the next decade.”

She wrote that in 2004. In Romancelandia I think critical mass has long since been reached—not necessarily because of all the fan fic writers turning pro (though we certainly abound), but because the same cultural influences and changes in mass communication that led to such a tremendous surge in fan fiction also led to a general shift in how we, as writers and readers, view the Id Vortex. The internet has taught people that whatever they’re into, they’re not alone. You can always find somebody online who shares and validates your desires. It’s a post-Rule 34 world, in which you’re never more than a few keystrokes away from, say, tentacle porn. On the other hand, there are still people who do not live on the internet, so there are still real-life contexts in which we are reminded that our various perversions are wrong and bad in the eyes of many*. We then recall these contexts the next time we surf for hentai (or whatever), and the frisson of the forbidden will spice our arousal, and so on, in an endless cycle. Shame: we’re soaking in it.

Brené Brown researches shame, which has got to be among the strangest jobs ever. If you haven’t seen her TED talks, go watch them. A key component of shame, according to Brown, is vulnerability. Unlike guilt, which deals with our feelings about what we’ve done, shame involves our feelings about who we are. Guilt is, “I’ve done a bad thing,” but shame is, “I am a bad thing.” Shame makes us feel unworthy of love, and afraid to take chances. We fear the loss of connection to others; if people knew the horrible truth about us, we worry, they wouldn’t want us. But in order to make a true connection, we must let our true selves be seen, make ourselves vulnerable. From a practical standpoint, we have to display our deepest, darkest, stickiest, most potentially shameful shelves in order to find the others who share our desires. In order to connect, we must risk.

Brené Brown researches shame, which has got to be among the strangest jobs ever. If you haven’t seen her TED talks, go watch them. A key component of shame, according to Brown, is vulnerability. Unlike guilt, which deals with our feelings about what we’ve done, shame involves our feelings about who we are. Guilt is, “I’ve done a bad thing,” but shame is, “I am a bad thing.” Shame makes us feel unworthy of love, and afraid to take chances. We fear the loss of connection to others; if people knew the horrible truth about us, we worry, they wouldn’t want us. But in order to make a true connection, we must let our true selves be seen, make ourselves vulnerable. From a practical standpoint, we have to display our deepest, darkest, stickiest, most potentially shameful shelves in order to find the others who share our desires. In order to connect, we must risk.

For SHAME!

This tension is pretty much at the core of every romance ever written. What’s different lately, or at least it seems so to me, is the growing number of romances—erotic romances in particular, though not exclusively—that are willing to make this conflict explicit. They go there. They soak in it. And then they somehow turn it into something else. Case in point: All Other Things (I could’ve used any number of Charlotte’s books as examples). The premise is simple enough: wife knows she should be content with awesomesauce-but-vanilla husband; wife harbors shame-inducing lust for edgy coworker; awesomesauce husband is secretly IMing edgy coworker; eventual kinky threesome ensues (obviously). But the events are almost unimportant, because the key factor in this book is feels, and the most important feel of all is that one where the character is mortified and aroused and doesn’t want to like what’s going on because she thinks she shouldn’t, but she really, really does, so much, even though she isn’t certain she likes who that makes her since it involves sex and also because threesome. And then it goes from them talking about how filthy it’s all going to be to being unbearably filthy and it’s all the most delicious thing imaginable.

The characters think about and express their shame, spelling out the part it plays in the menage so that it’s almost as if the wonkiness of their sexuality is a fourth participant in the affair. And for all it’s a dark book, there’s an odd cheeriness in the delight the characters end up experiencing. Yes, it’s dirty, but once they reach a certain point, they’re gamboling and wriggling in the dirtiness like frisky, overexcited puppies. In effect, they’re fetishizing shame (which, in case this wasn’t clear, is awesome), which transforms it, and transforms how they view themselves. Their enthusiasm for how the shame itself makes them feel crowds out their previously held notions about whether wanting to engage in those shameful acts makes them bad people. At the end of the book they do still want to do those things…they just feel differently about what those things mean.

It becomes a story about how we wrestle with our shame. How it is possible, maybe even necessary, to make that struggle explicit in order to transcend shame. How we come to terms with—come to accept and embrace—what our desires and needs do or do not say about us.

Once I started to think about this use of shame in modern romance writing, I couldn’t stop thinking of examples, most of them from the last decade or so (not necessarily just contemporary romance or erotic romance – Sherry Thomas and Courtney Milan, about whose historicals I’ve often flailed here, both excel at exploring how characters mediate their own shame). And how different these books are, how much more willing to explore and ultimately accept potential ugliness in protagonists, than the standard “shameful-act-is-shameful-and-must-be-atoned-for-before-love-is-earned” model of so, so many romance books that have gone before and will surely come after. This may seem harshly realistic, a quality we don’t always associate with romance, because in the real world shame works this way. It doesn’t usually lead to atonement and true love…in reality we are going to continue googling for XXX-rated Harry Potter Giant Squid stories even if we do find love, so instead of feeling like we’re bad people for enjoying weird stuff, it makes sense to find love with somebody whose response to that tendency is, “Filch/Squid is my OTP! Mah fic recs, let me show u them!” But in a way it’s also deeply romantic, this notion that we can find a love who not only loves us for ourself but embraces what we might otherwise think of as the worst in ourselves. Maybe it’s the new romantic.

Once I started to think about this use of shame in modern romance writing, I couldn’t stop thinking of examples, most of them from the last decade or so (not necessarily just contemporary romance or erotic romance – Sherry Thomas and Courtney Milan, about whose historicals I’ve often flailed here, both excel at exploring how characters mediate their own shame). And how different these books are, how much more willing to explore and ultimately accept potential ugliness in protagonists, than the standard “shameful-act-is-shameful-and-must-be-atoned-for-before-love-is-earned” model of so, so many romance books that have gone before and will surely come after. This may seem harshly realistic, a quality we don’t always associate with romance, because in the real world shame works this way. It doesn’t usually lead to atonement and true love…in reality we are going to continue googling for XXX-rated Harry Potter Giant Squid stories even if we do find love, so instead of feeling like we’re bad people for enjoying weird stuff, it makes sense to find love with somebody whose response to that tendency is, “Filch/Squid is my OTP! Mah fic recs, let me show u them!” But in a way it’s also deeply romantic, this notion that we can find a love who not only loves us for ourself but embraces what we might otherwise think of as the worst in ourselves. Maybe it’s the new romantic.

On the other hand, maybe all this means that love is really just an acute form of confirmation bias? Perhaps that has always been true. I have no idea. Feel free to discuss amongst yourselves.

Gosh, and I didn’t even get to naked Fassbender (amusing, and NSFW). I could have also said many things here about shame and the collected works of Cara McKenna, by the way, or discussed Ruthie’s instant wonko/shame classic, About Last Night, but I’d rather gather recs. What’s your favorite work of horribly delicious piping-hot shame?

[*protip: if somebody isn’t sure how to check their email, that isn’t a person with whom you should broach the subject of tentacle porn. Or whatever.]

You know who else tackles this, really really well? Victoria Dahl. It’s such a theme of hers, especially the shame women feel over their sexuality, and the ways culture shames them– heroines finding their desires and freeing them from shame, or feeling the shame and sort of reveling in it anyway, are near constants in her books. And actually, that theme is my favorite Dahl-ism. It’s what made me a fan in the first place.

Oh, YES, I should’ve added her to the list. She does good male shame-as-conflict, too. Have you read Wicked West?

Yes! You’re right, that one does have a hero who is shamefully conflicted, too.

I thought the whole Donovan Brothers series was great with this theme, too.

One of the great things about Victoria Dahl, too, is that she has shame and guilt. Sometimes the characters are fretting over their past decisions and sometimes it’s over how they feel about their past. Resolution of shame is tricky, though, and I think Dahl handles it well.

I haven’t read any of her contemporaries (because I’m a big historical romance ho when it comes to reading). They are on my Infinite TBR™.

Now I’m thinking and wondering what love looks like when it doesn’t involve the mutual sharing and acceptance of shame. I’m sure it’s out there somewhere, for people who have no shame, or so little that it doesn’t occur to them to mitigate it by finding someone who will accept and possibly endorse whatever a body finds shameful. Or maybe there are those who don’t share any of their shame and that’s exactly why their love works. But it’s hard for me to imagine it.

Shame is a funny thing, since it’s completely socially constructed. And that then makes me wonder what love would look like in a world entirely without shame, and whether the very concept of love, for that reason, would cease to exist.

Of course, I have zero answers to any of these questions, but I love that this post got me thinking and generally tying my brain in knots. LOVE.

The thing about shame being a social construct, and the way the internet gives almost everyone a chance at instant validation for things about which they’d otherwise be ashamed, is what made me think that if you’re not ashamed, you have nothing about which to feel vulnerable, and so you aren’t risking anything by opening up to somebody else. I think it turns love into just confirmation bias. Matching up the mutual validation/preferences. But I don’t know…dating websites are all about this, right, they do it by algorithm, and a lot of people find compatible partners that way I guess? It seems devoid of mysticism to me, therefore suspect, because love should involve an element of ineffability.

The id vortex is such handy shorthand, isn’t it?

I think you got at a lot of what I was trying to get at in my post on this subject a few months ago–there really is something compelling about shame and stories that wallow in it can be utterly absorbing to read. There is something about this–I call it a sensibility–that I think really is bleeding into romance from fanfic.

I think there’s a tension between the id vortex and humiliation squick that’s very interesting as well.

Ooh, yes! Humiliation kink vs. humiliation squick. A battle royale! I believe that kink.com depends quite heavily for its existence upon the appeal of that dynamic for so many of us.

But it’s a fine line in a romance. Some things can become no-longer-shameful to that character, and the reader is okay with that, but there are things most readers won’t accept in their romance protagonists because they’re just too psychologically or emotionally icky. And that line differs from reader to reader.

I really enjoyed this post. I don’t have anything to add except that I immediately bought the Charlotte Stein book and am enjoying it immensely!

I love the phrase “mediate their own shame.” In the comments for Mary Ann’s beautiful post last week we were discussing the questions we begin with, like what is at stake and what will be lost. The question I came round to was: how does this character separate themselves from the love they need/want/deserve? Separating from love is almost always about shame. Most of my life is about shame and simply can’t imagine writing characters who aren’t struggling with it because every person I know is struggling with it in some ways.

Part of my attraction to romance and HFN/HEA endings is that I want there to be something beyond/instead of shame and so I read romance partly because of that hope. Or wish. Maybe it’s my dearest wish: love without shame.

For me, the most interesting stories have internal struggles of feeling worthy of the love in front of us, of learning to allow need and let others need who we are and not some imagined version of our potential selves. Absolutely the best stories for me are about “ how we wrestle with our shame.”

That’s the key really, we each must wrestle with our own. No one can rescue us from that struggle.

My fascination with that fundamental question is why I suck at plot. Give me characters all day long, but what they do while they’re figuring out their shit so they can move forward is largely just window dressing for me.

I’ve been thinking the same thing and trying to pay attention to how others deal with this.

Sometimes plot takes over. Sometimes the internal struggle takes over. Sometimes neither of them are working out.

When I think about the times I’ve been falling in love, the world and it’s requirements and my connection to it have fallen away and all of the drama was internal, so it seems natural to me to focus my writerly attentions there.

It really is connection that generates the shame, isn’t it? It’s why it’s so deeply, achingly delicious when despite our best efforts to conceal shame, we reveal ourselves.

The chestnut is “write like your parents are dead,” for a reason, to give you some imagined space where no one can see you naked. But then, you’re walked in on, what’s more, you’re *lucky* in this business, if someone walks in on you. And you’re caught, naked, maybe with your hand between your legs, and what’s more, it’s what you *asked for.* You were hoping for it.

Because shame doesn’t exist when you’re naked with the door closed, only when you’re caught, when the connection is made. So that seems to me, the wedge to drive your muscle into, the space just before you’re caught, and want to be, but don’t want to be, and the space after, when almost anything can happen.

We see in Charlotte’s book that when she put her muscle into this space, that’s exactly what happened–everything, anything. She wrote an entire book about the space just before we’re caught, and what happens after, and it’s fantastic. It’s a loss of privacy, but the entire world happens after that loss, it turns out, privacy wasn’t precious, at all, not worth protecting, and the long, slow beats of shame were where all the life was, all along.

So, that’s why I say shame IS connection. It doesn’t exist without it. Without connection, you’re naked in a locked and private room. When you hear the click of the key in the lock, well, that’s when your heart starts up and the blood comes to the surface.

Right there, is where the story starts, just as you’re caught.

That, yes, exactly. Leaning into, biting into and gnawing on with relish, that specific moment where shame is actualized.

And I would marry you all over again for, “the long, slow beats of shame were where all the life was, all along”. You brilliant thing, you.