Hi everyone! Ruthie here.

I’m delighted to announce that with this post, Alexis joins Team Wonkomance as a regular contributor. We’ve added him to the bio page, plopped him into the rotation, and everything! From now on, he is free to natter at you with no introduction, at random times.*

* Although probably it will mostly be Tuesdays and Thursdays, like the rest of us.

Take it away, Alexis!

———

I’ve recently been trying – not entirely successfully, let’s be honest here – to get my head around category romance as part of my romance reading education. Somehow or other I picked up a recommendation for Vampire Lover. I think I’d got the impression it would be interesting. And, yeah, I guess it was. In a faintly euphemistic sense.

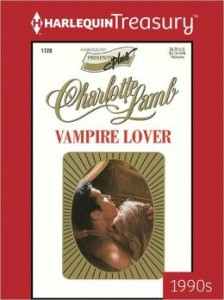

History and the development of the romance genre is seriously above my pay grade, so I’ll just tell you it’s Charlotte Lamb’s one hundredth novel (holy pink palazzo, Batman) and that it was published in 1995 under the Harlequin Presents imprint. Tragically, this is actually the category line I know best (which is to say I’ve read, um, maybe three books so I shouldn’t get ideas above my station here) and I’ve sort of come to think of it as Harlequin Presents Really Rapey Men and the Woman Who Love Them. Which does, in itself, provide a fascinating context for what happens in Vampire Lover but, for me, is simply not enough to mitigate everything I found deeply troubling about it.

Trigger warnings, because this is, as they say, sexual abuse all the way down.

Vampire Lover kicks off with a darkly mysterious film director called Denzil Black sweeping into the heroine’s hometown to buy – for no apparent reason – a ruined Victorian pile called Dark Tarn. Since, obviously, if you’re called Denzil Black you can’t really live in Honeysuckle Cottage or at Sparkly Towers. For the first half of the book, the hero and heroine (her name is Clare, by the way) barely see each other. She lets him rent her cottage while he renovates Dark Tarn, and he hangs out on the periphery of her life, being vaguely creepy. Women associated with him seem to fall victim to a strange malaise which leads Clare to convince herself that Denzil is an emotional vampire, who feeds off the vulnerability of women.

Meanwhile, her radiantly innocent sister, Lucy, is engaged to some guy who is currently in Africa, and she’s growing increasingly dissatisfied with the distance. When Denzil offers her a screen test for his next film, Clare flips out because she thinks Lucy is going to break off her engagement to Absent Africa Man and decides to take matters into her own hands. By which I mean, she slips Denzil some sleeping pills, ties him to the bed, makes him tell Lucy the screen test is cancelled, and then takes advantage of Lucy’s disappointment to send her to Africa after her fiancé. Oh, and in the middle of all this she rapes Denzil. When she gets round to untying him from the bed, they end up having a long conversation about his tragic past and her instinctive mistrust of him. He briefly handcuffs her to him because, oh, Reasons, I think to make her confront the truth of her desires and the mutual powerlessness of love. Then they have consensual sex.

But let’s rewind to the, uh, rape shall we? I realise I’m kind of on dodgy ground here because the place of rape in romance is, y’know, complex and, in recognition of this, I’ve always tried to take a fairly neutral stance. Which is one of those comments that would sound absurd out of context. Obviously I don’t have fairly neutral stance on sexual abuse in general but, in this genre, rape-by-hero is a trope and consequently has a lot of, what you might call, narrative context behind it, alongside the political context of reactions to and against sexual liberation and rape culture. Cara McKenna’s Willing Victim, for example, derives a lot of its subversive power and, let’s be honest here, erotic charge from its engagement with a massive taboo but also the complicated history of rape within the romance genre itself. So I guess what I’m circling here is the idea that, although it’s problematic to act as if fiction is hermetically sealed from reality, it’s equally problematic to assume that fictional events always, and only, relate directly and literally to the lived-in world. And this is particularly relevant when you’re dealing with issues like rape in fiction.

That said, I had lot of trouble with Vampire Lover because rape-by-heroine is comparatively rare in the genre and, therefore, it’s harder to interpret, especially if your personal reaction is a bit visceral (which mine was). It’s not a trope on its own terms, with its own history and context, it’s only a reaction to a trope that already exists, and derives history and context from that. And, obviously, you’ve got the whole Harlequin Presents Rapey Heroes thing going on in the background. So, because of this, I can see why people conclude there’s something just inherently subversive about Clare raping Denzil, although that’s not a reading that works for me. For an alternative (and less ranty) perspective, I recommend this blog post by Sandy Schwab. Err, I know I’m just about to disagree with basically everything she says, but she’s coming at the text very differently from me. In short, what I saw pretty incontrovertibly as rape, she saw as a forced seduction, and her reading springs from that and is, in general, much more concerned with Lamb’s importance in the development of the genre.

So, let’s get up close and personal with the text. Basically what happens is that having Denzil at her mercy enables Clare to both admit to, and unleash, the passion she has long since felt for him. So, high on power, she has sex with him while he begs her not to.

He gave a hoarse gasp. ‘Clare…’ His dark eyes were enormous, glittering. ‘Untie me,’ he begged. ‘We can’t make love like this; it’s sheer hell… I’m going out of my mind!’

There are, admittedly, some aspects to the scene which some readers could possibly find ambiguous. Denzil does sexually desire her, her actions arouse him to the point that he responds verbally positively to some of the physical stimulation (‘Oh… yes… Clare, yes,’ he breathed against her mouth) and the majority of his objections are centred on the way they’re having sex, rather than the fact they are.

But, to me, that doesn’t make it any less rapey since one of the really harmful things about rape culture is the idea that consent is general. That if a woman agrees to have sex with a guy in a nightclub toilet, it’s then okay for him to bring his three mates in there as well. Hell, it wasn’t so long ago in this country at least that it was considered legally impossible for a man to rape his wife. It is fundamental and axiomatic to me that a person’s right to choose what happens to their body applies moment to moment and to specific acts. It does not matter how much Denzil wants to boink Clare, or whether his body responds (because, seriously guys, an erection is not consent) he does not want to do it while he’s tied up.

And then there’s Clare’s utter disregard for his lack of consent, her obvious pleasure in it and her seemingly textually supported belief that this represents some kind of justice, not just for his behaviour to her or his behaviour to other women, but for the whole concept of gender inequality in general:

‘It’s an interesting experience, having a man entirely at my mercy. For most women it’s usually the other way round. There’s a lot of talk about equality, but men still have all the advantages — they’re bigger, tougher, and the social rules favour them. I can’t walk down a street at night, alone, without being afraid; I’d be wary of going back to a man’s flat after a date, or being alone with him anywhere unless I’d known him for years and trusted him.’

There is so much wrong with this, I don’t even know where to begin. On the one hand, I totally get that Clare, and perhaps Charlotte Lamb, are frustrated by the many ways in which society disempowers and marginalises women. On the other hand, she’s kind of busy raping a dude right now. It’s true that institutionalised oppression is an emergent property of the behaviour of large groups of people, particularly people who are privileged within those institutions, and it is important for people, particularly people with privilege, to take responsibility for their actions and their behaviour, and to try their level best not to be part of the problem. It is not, however, okay to punish specific individuals for the injustices inherent in their society.

Perhaps I’m overreacting but this sequence reads to me as exactly the kind of cartoonish misandry that people invent as a way of bashing feminism. Raping a man is not fucking the patriarchy. As every feminist text I’ve ever read has taken pains to point out, patriarchy hurts men too and one of the ways it hurts men, incidentally, is that experiences of male rape survivors are minimised because men are supposed to enjoy sex unconditionally, to be incapable of being victims and, of course, to have a moral duty to be able to physically defend themselves. One of the particularly fucked up things about social attitudes to male and female sexual dynamics is that if a man does get raped by a woman society deems conventionally “hot” the usual reaction is that he is “lucky”.

And I do realise that I’m not actually talking about a real person here and that Denzil is ultimately a fictional construct who isn’t going to have to spend the rest of his life being traumatised for an experience society tells him he should be grateful for but I just found this whole scenario almost impossible to parse on a personal level. And I do worry that it’s hypocritical of me to take such a hard stance on the rape of a male character when I’ve tried to take a neutral one on the rape of female characters. I think, for me, it is not the rape of a man that is the problem here, it’s the fact that I get a very uncomfortable feeling that this rape is being presented as justice.

That said, putting aside my instinctive reactions, there’s no denying that the way this scene functions within the narrative (and perhaps the genre) as a whole is quite interesting. There’s a really fascinating paper by Angela Toscano which explores the rape trope in romance novels narratively rather than mimetically. One of the advantages of academic writing is the ability to look at texts purely as texts without necessarily having to concern yourself with their more personal impacts and, as someone who writers about books from a very personal perspective, Toscano’s paper doesn’t really help me like Vampire Lover any more than I did. But it does offer me a way of understanding the rape in the wider context of the genre. And, although I’m having trouble accepting the novel as subversive (since I don’t believe there’s anything subversive in equal opportunities rape) I do find it interesting to look at Clare’s actions through a lens specifically designed for understanding the behaviour of male characters.

In her paper, Toscano identifies three “types” of rape, The Rape of Mistaken Identity, the Rape of Possession, and the Rape of Coercion, and it’s the last I really want to look at here. To quote Toscano directly:

…the Rape of Coercion or forced seduction […] is committed in order for the hero to gain knowledge about the identity of the heroine.[1]

What’s interesting about Vampire Lover is how little Clare actually knows about Denzil before she, um, before she rapes him. She is obsessed with him, certainly, but except for a few very fleeting encounters, they barely speak or learn anything about each other. Which again makes Toscano’s paper very relevant because she argues that the Rape of Coercion is as much driven by language as it is driven by, for example, power, emotion, jealousy or the need to possess.

Throughout Vampire Lover, the novel presents Clare as she sees herself or, perhaps more accurately, as she would like to be perceived: as a cool, controlled, not particularly passionate person. There are, however, hints that this is, if not a façade, at least not the whole truth; for example, she compulsively watches Denzil’s films, which the book slyly tells us are darkly erotic in nature. But it isn’t until she has Denzil literally at her mercy and ready for a rapin’, that she really begins to articulate the reality of herself and her desires. Let’s be clear here, her desire is to rape a dude, but at least she’s talking about it:

‘I think I want you,’ she said conversationally, and saw sweat spring out on his cheekbones.

Toscano explores the idea that the RoC is a form of interaction, albeit forced interaction because the rapist (seducer) wants (demands) a response – verbally and physically – from the victim/forced-participant/seducee that will allow the rapist access to the true self of the other person. And although Clare doesn’t trouble herself unduly about Denzil’s actual consent, she is deeply engaged in his responses, both verbal and physical.

She was moving against him, intensely aware of every movement he made in response, his hips lifting to meet hers, the restless shift of his thighs as he tried to manipulate her between them, pressing against her, struggling to get her closer.

Both the Rape of Mistaken Identity and the Rape of Possession are, to some degree, based on misperceptions or misunderstandings of the heroine i.e. that she is whore, not a virgin, or shagging someone else. The Rape of Coercion can, by contrast, be seen as a need to move beyond a knowing based on signs that could be false (like Heather in The Flame and the Flower, running unprotected through the docks in her “I’m a prostitute” dress). Clare builds an entire mythology around Denzil – first the novel teases us with the notion he might literally be a vampire (we only ever meet him in the dark, he likes bats, the women around him seem to fall prey to strange lethargies, Clare fails to see his reflection in a mirror) and then she decides he’s an emotional vampire, preying on all these mysteriously lethargic and vulnerable women. It’s only after she’s raped him that she can finally begin to accept that he’s a person, a rather lonely person who’s had pretty a shitty life. To which he can now add, y’know, being raped.

So, on this purely textual level, I can see how Clare’s rape of Denzil is narratively subversive. If raping the heroine can function as a way for the hero to confront, and break down, the “unknowability” of the other (leading to mutual rebirth, recognition of identity and I-love-yous etc.), then raping the hero is, indeed, equalising as it acknowledges the mutuality of this violent desire to know. I mean, why should heroines stand around waiting to be raped when they can do it for themselves? Okay, that’s glib of me, but I can actually see real value here. Not in this particular scene, or in the rape of male characters in general. But I think a lot of the pleasure of what I believe have been termed “extreme” romances, especially when it comes to hero behaviour, is the fact that there is something quite powerful about the idea of love/desire/need so strong that it crashes right over moral, social and personal barriers (including the word “no”). So I like the notion that heroines – that women – can be agents in this, as well as recipients of it. I think that’s powerful and important.

But, unfortunately, I just don’t think it works in Vampire Lover, even narratively. Before Clare knocks Denzil out with sleeping pills and handcuffs him to the bed, he puts the hero moves on her by trapping her against a wall and being threatening (while she tries not to get turned on). She taunts him with this as she assaults him:

‘A game was it? You touched me against my will, remember? Like this…’ She ran her long index finger over his chest… ‘helpless was the word you used – you said we were at war, and I was a helpless prisoner. Well, look who’s the prisoner now. How does it feel?’

I’ve already expressed in some detail my feelings about rape-as-feminist-act. But to stick to narrative, what we have here, I think, is a challenge to specific genre tropes i.e. the fact that if somebody you didn’t know very well trapped your hands and started growling about you being their helpless sex prisoner you’d freak the fuck out. You can see the rape scene, with its echo of this earlier one, as being largely, and personally, about Clare and her pathologies but, given the passage I quoted earlier about gender inequality in general and the fact Vampire Lover is a Harlequin Presents, it’s hard not to read it more broadly, as being both about women and the romance genre.

Power is an implicit theme early on in Vampire Lover and an explicit one by the halfway point. Clare is terrified of love (and its expressions, including sex) because she sees it as necessarily and inherently disempowering. Even after the declarations, she’s still wary:

Clare gave him a secretive glance through her lashes. This was something else it would not be wise to tell him— that he already had a strong and terrible power over her.

It’s only Denzil who seems capable of recognising that love need not be about power and, if it must be, it can mutually empowering as well as mutually disempowering. If I had to find one thing I liked about Vampire Lover, it would be just how unresolved it feels at the end. I mean, they barely know much more about each other than they did at the beginning of the novel, and Clare is still clearly still totally nuts and riddled with issues. The fact they they’re probably in love with each other doesn’t actually seemed to have solved or changed anything.

But, again, what troubles me is the extent to which I read the novel as supporting Clare’s nutbaggery. For me, it wavered unhelpfully between specific tropes of the genre and wider generalisations about relationships between men and women. One of the preoccupations with the rape scene is an implicit acceptance of the idea that who does what to whom carries an inherent dynamic of dominance and submission and the only way for Clare – or, perhaps, women – to avoid the submissive role is to forcibly claim the dominant one. Again, I find it hard to see this as either empowering or subversive because, to me, all it does is reinforce patriarchal notions about power, sex and gender norms.

[1] A. Toscano, ‘A Parody of Love: the Narrative Uses of Rape in Popular Romance’. Journal of Popular Romance Studies, 2.2, April 2012, viewed September 2013, http://jprstudies.org/2012/04/a-parody-of-love-the-narrative-uses-of-rape-in-popular-romance-by-angela-toscano/

I am a contemporary of Charlotte Lamb’s books. That is, I was in my 20’s in the 1980’s and reading them then. I’m now collecting Lamb books from op shops and reading them almost as a way of interrogating my past and to see if they make a kind of sense given we share the context of the times. So I’m really interested to read your discussion of this book.

Firstly, the synopsis reminded me a little of the Georgette Heyer novel “The Devil’s Cub” where a marriage begins when a sister stops the hero from eloping with her younger sister. There isn’t any rape or even pre-marital sex but there is the element of risk.

A contemporary romance “This Heart of Mine” by Susan Elizabeth Phillips has Molly the heroine rape Kevin. THoM was published in 2000. If you look at THoM reviews on Goodreads you will see that 5star reviews ignore the rape and 1 & 2star reviews rate at that level because of the rape. This is one discussion of THoM that digs into the rape: http://readreactreview.com/2010/03/06/review-this-heart-of-mine-by-susan-elizabeth-phillips/

Molly like Clare is neurotic and mad and a stalker but I don’t think either author thought of them as such. There is a sort of reification – if the heroine does it, because she is the heroine it is automatically OK. So by default, behaviour which in another person would be pathological, in the heroine’s case isn’t. This highlights how romance genre books are read against a template I think.

Taking as a given that the point of rape is that the rapist wants to take power from the victim what is the agency Molly and Clare gain from their actions? Does what they take make each of them the eponymous ‘vampire lover’ because their actions are to feed something within themselves only? There is no exchange or reciprocity. Thinking about both these books leaves me agreeing wholeheartedly with your concluding paragraph.

Thank you for the comment. And for wading through what was pretty much a wall of text :)

I’m a huge Heyer fan – and now you mention it, I do very much see that connection between Devil’s Cub and this. One of the things I find pretty fascinating about DC is the way that sense of risk, as you put it, ends up being sort of interrogated by the novel. Mary shoots Vidal because she feels *genuinely* threatened by him, and completely out of options – and I think what’s really interesting is the way the extremity of her reaction is the catalyst for his beginning to understand her, and the inherent power disparity between them, because gender, society, etc. etc.

Whereas, yeah, making someone powerless in precisely the way you feel you’re powerless, to my mind at least, just affirms power structures rather than dismantles them.

Thank you for the SEP links – I’m probably not going to be seeking out more rape-by-heroine books for my personal reading pleasure, but it certainly leads to interesting discussions. To be fair, from what I’m read, the template applies equally to heroes and heroines. Rape-by-hero is much more common and, once again, there’s this sort of implied idea that because the hero is the hero, any sexual misconduct is either okay, or will be okay in the future. Because obviously heroes aren’t rapists, they’re heroes :/

Glad to see you’ve found a new nest.

I won’t wander off into a discussion of rape in romance. I have my own ideas about that, but found your thoughts and Angela’s engaging. I now have more to chew on, especially with regard to the predatory nature of seduction in general.

What I do want to comment on is the failure of the book to engage your interest enough to propel you through what appears to be an author delivering a lecture and forgetting to mask it properly. While I haven’t read Vampire Lover, I have run across this problem with other authors. Mary Balogh drowned any narrative power of her Simply series under a barrage of I Am Woman Hear Me Roar. I wonder about the reason for the intrusion. Do authors come to a point in their career where they have a compulsion to be significant rather than authentic? It puzzles me and, in the case of a gifted writer, can be rather scary. The premise of Vampire Lover sounds wonderfully gothic, Dark Tarn and all. Give it a first person narrative, a bit of extra length, some proper festooning of a less myopic lecture, and I can imagine a delightful, and possibly subversive, tale, but probably not a Harlequin Presents.

I hope you find some category fiction eventually that will appeal to the reader in you. Given its constraints, I don’t find category as fruitful as other branches of the genre, but there are good books to be found.

As a male rape survivor of a female (possibly serial) rapist, I can say without reservation that many women view it as “justice” when a man is raped by a woman. A woman I had met that night bought me a few drinks. I was under 21, so she bought them. I got woozy and passed out soon after securing a motel room next door. There was zero consent and she did what she wanted more than once. Once the alcohol and drugs faded, she used a nasty threat to do it again. She clearly enjoyed the control. After telling my story publicly, I’ve heard from all manner of male and female victim-blamers and haters who viewed it as “impossible”, something I should have “enjoyed”, and 8,000 other excuses for her actions. I was even confronted by a feminist I shall not name (she later apologized privately) who said she was skeptical of a woman committing rape and wanted to hear her side of it. That last one was infuriating and I will never forgive her for that. A rapist doesn’t get a vote.

Anyway, as triggering as it is likely to be, I will likely read this book now to see how it is handled. A recent romance novel by Susan Mac Nicol (Cassandra By Starlight) handled the topic of female on male rape fairly well and the scene was loosely based on my own experience. You might find that an interesting read. It triggered me hard as I felt like I was back in that room again, but that was because she showed it as a horrible act and not as a twisted romantic encounter.

How did you find Charlotte’s portrayal of the aftermath of the rape? Was it the usual instant healing with not aftermath of note? Or did the survivor feel traumatized?