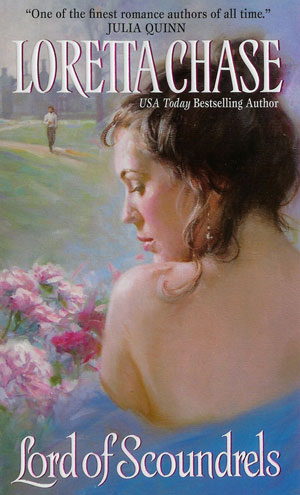

One of the first waves of romance books I read was Lord of Scoundrels by Loretta Chase, which is really a staple of the genre. I loved that book and went on to glom Loretta Chase, as well as much of the historical romance canon. I also re-read Lord of Scoundrels several times.

It was only one maybe the fifth re-read that I noticed, I mean *really* noticed, that the heroine SHOOTS the hero. Like, with a gun. And a bullet in his shoulder. And that the narrative, from my interpretation, basically shrugs this off as “he had it coming.” I mean, that’s weird. It’s weird that I didn’t fully realize that beforehand, almost as if my brain refused to acknowledge the scariness of that situation in what is an almost humorous book. It’s also weird that the book managed to be as popular as it was, considering. I guess that’s a kudos to Chase for making it work.

It was only one maybe the fifth re-read that I noticed, I mean *really* noticed, that the heroine SHOOTS the hero. Like, with a gun. And a bullet in his shoulder. And that the narrative, from my interpretation, basically shrugs this off as “he had it coming.” I mean, that’s weird. It’s weird that I didn’t fully realize that beforehand, almost as if my brain refused to acknowledge the scariness of that situation in what is an almost humorous book. It’s also weird that the book managed to be as popular as it was, considering. I guess that’s a kudos to Chase for making it work.

Thinking about the heroine shooting the hero definitely altered my perception of the book, but it didn’t make me hate it. I still love the book, and still love Loretta Chase, only now there is a little WTF!? bookmark inserted in that love. I’m okay with that. There are WTF!? bookmarks inserted in my actual real life relationships (though no shootings, thankfully). And I am prepared to be far, far more permissive with fiction than I am with real life.

Which brings me to the inspiration for this post, which is the recent discussions online about dubcon and non con. Actually I believe that was kickstarted by fellow wonkster Alexis’s post about m/m having more dubcon than m/f. But the fact remains that having more dubcon in m/m would not, could not be troublesome if dubcon was not inherently troublesome, and it’s that trouble that I wanted to explore in this post.

And really, similar arguments are used for antiheroes or even alphaholes. The idea that “it wouldn’t be okay if some guy tried to do this exact thing to me, therefore this is not okay in a romance.” I mean, that makes a certain kind of sense.

Though I have to admit, that’s not how I read.

It’s not how I read general fiction or literary fiction or romance. Sometimes I don’t know if that kind of restriction is being placed on fiction in general or romance only. Is it the HEA that then makes the requirement for good behavior?

And when I read a book with bad behavior, am I exploring it or am I tacitly absolving it? The subconscious is a pretty mysterious place to me, so I don’t know the answer to that. But I also think that restricting characters to behavior I would personally do and/or approve of is not the right direction. I can choose not to read a certain book, of course, but suggesting that it’s problematic or that other people shouldn’t read it is another thing entirely.

But I’m definitely not okay with all bad behavior either. Sometimes I get pissed as hell and then I rant. I’m not sure there’s a specific line I can put on when I’m okay or not okay with it. It depends on the context, and to me, that’s a good thing, each book evaluated on its own merits and arguments.

One of the factors that influences my acceptance is the character’s self-awareness. For example, I’m far more likely to be interested in a hero who does bad things and knows they’re bad but does them anyway. That is interesting to me. Why does he do them? What happens next after he does them? Does he ever regret them? That’s a very different scenario than reading about a hero who, in the case of dubcon, doesn’t even understand how consent works. That’s not interesting as subject matter to explore, to me.

I think that explains why some (most?) of the old dubcon bodice rippers don’t work for me. Like when the hero coerces her but then tells her she deserved it and that it’s okay because she had an orgasm and he believes that. Because in addition to being an asshole, he’s a stupid asshole and there’s nothing interesting about that. Then at some point I wonder if the author also doesn’t understand consent, and then I get angry at like, all of society.

But with To Have and To Hold by Patricia Gaffney, that book worked for me because my interpretation was that he understood exactly what he was doing. And she understood exactly what he was doing. They were both fully aware, fully intelligent, as they acted against each other. Watching them move closer in spite of themselves was a beautiful thing. I fully believe that it’s possible to acknowledge what he did was wrong, and should never be done in real life, and still appreciate that book. In fact, I feel like that’s the core story of the book.

And some people may disagree with me, in their interpretation of that book. Still other people may not even care about interpretations, because it’s not enjoyable for them to read that kind of thing. My point is *not* to encourage people to read the book or to like the book, but just to say it’s important to be able to have that conversation about it, for those of us who want to. Reading about a certain type of behavior doesn’t mean we support it.

The truth is I don’t know how my subconscious will process everything that I read. I don’t know what I’ll think about some new situation, some new argument, some new book–but what I love about reading is finding out.

Ah, interesting. I did a post about dubcon in older historicals last week, but yours is better. What I didn’t take into account was this:

“One of the factors that influences my acceptance is the character’s self-awareness. For example, I’m far more likely to be interested in a hero who does bad things and knows they’re bad but does them anyway. That is interesting to me. Why does he do them? What happens next after he does them? Does he ever regret them? That’s a very different scenario than reading about a hero who, in the case of dubcon, doesn’t even understand how consent works. That’s not interesting as subject matter to explore, to me.”

There’s a scene in Laura Kinsale’s Prince of Midnight that made me uncomfortable, but unlike some other similar scenes in other books, it didn’t made me hate the character or the book. And you’ve just pointed out why. S.T. understands that even though Leigh has said yes to sexual contact, she still feels coerced and he immediately hates himself for taking advantage of her. There’s also a rational explanation for his behavior. I had come to the conclusion that I excused it because I loved the character, but you’re right: self-awareness is the defining factor here.

That said, my particular problem with dubcon is just that: my problem. I wouldn’t suggest that no one should ever read or write a book that features scenes that make me uncomfortable. I know that a lot of people enjoy them and now I can add another reason why; the chance to have a conversation about consent. And you’re right, I can’t always predict what will and won’t make me uncomfortable so any given book is usually worth a try.

As I mentioned on twitter, I looove Laura Kinsale. I haven’t read that one yet, but my favorite by her is The Shadow and the Star which has a few interesting sex scenes. I suppose you’d call them dubcon, because there is some question, though it’s not a forceful relationship. But that’s really the point, that she can play with knowledge and consent and understanding in ways that are right for the characters, but that might not be right for the reader.

Innnnteresting! I think we all have a “bandwidth,” for lack of a better word, in which we want our escapist fiction to fall. I tend to like grittier, realistic contemps. So small town romance irritates me, because it feels like a bubble world. Therefore, I need my characters (as well as my setting) to behave in a way which passes muster with my understanding of reality. And if I wouldn’t tolerate, say, pushy alphadude behavior in real life, I don’t love it on the page, either.

Unless the author really sells it somehow. And then I may just love the heck out of it.

I once heard Jennifer Egan say that the whole job of fiction was to explain characters’ outlandish actions via emotional revelations. (I’m paraphrasing terribly here.) So when the execution works for me, almost any behavior can be made rational. And if the storytelling doesn’t work, then even something as mundane as a small town rubs me the wrong way.

Good points, Sarina, especially about certain authors just pulling things off. I think a lot of times it *does* boil down to execution, but in that case, I also think it’s important that our criticism is “poor execution” and not “this behavior is inherently problematic and should never be included in books.” Not that you’re saying that, but I see those used interchangeably sometimes when really they are miles apart.

I agree with all of your general arguments, though not necessarily your specific interpretations. In a society in which dueling was illegal but tolerated, so long as no one died, the characters’ reaction to the shooting in Lord of Scoundrels is plausible, I think.

Like you, I have a somewhat flexible threshold for bad behavior, depending upon context and execution.There is a scene in Liz Carlyle’s The Devil to Pay that is very uncomfortable with regards to consent but very well executed with regards to the characters’ thoughts on the matter (and the hero gets his comeuppance of sorts). I was far more disturbed by a scene in the same author’s Never Deceive a Duke, although it involved less physical aggression, because the hero had reason to believe the heroine was not in her right mind. That book really disappointed me, especially since I have greatly enjoyed most of her other books.

I stopped reading Gaelen Foley entirely after My Ruthless Prince. It was extremely Old Skool in its power imbalance between the hero and heroine and his habitual rapey behavior toward a woman he seemed to consider his personal property. Yuck.

You bring up an interesting point with regards to the laws and morality of the time period. Probably for that reason I more commonly see dubcon and other “bad behavior” in historicals and paranormals where the rules of society are unlike ours. So that’s definitely a factor, but I’m not sure it totally excuses the heroine in Lord of Scoundrels. It was, after all, not a “fair” duel, and he might very well have died no matter how good a shot she was. I’m not sure I could ever be comfortable with her actions, but I think you can still enjoy a book you don’t agree with 100%.

I do understand your discomfort with the Lord of Scoundrels shooting. I think it mirrors our modern society’s ambivalence toward guns. I grew up in NRA country, where stupid behavior with guns is unfortunately common. That makes it easy for me to believe that the heroine could be foolish about the potential consequences of her actions without necessarily being a bad (or unteachable) person.

Great post! And I love the observation about self-awareness; it changes everything. Because a jerk behaving badly is capable of genuine change, but a jerk who doesn’t know he’s a jerk … well, that’s a long road.

I think about some of these questions a lot. And one of the conclusions I’ve come to is that how we feel about characters in romance is heavily affected by the whole notion of an HEA.

Jayne Ann Krentz has written/spoken about the fact that genre books convey our cultural values–the characters are expected (by readers) to embody values and behaviors that we–society at large–put our stamp of approval on. When they receive the HEA, it’s a reward for good behavior, for right values.

So any character who wins the HEA must be someone we can admire, which means they must be redeemed to the point of being forgivable. But if they’ve done something we can’t forgive–well, then the romance WRITER has screwed up (I think this is part of why readers can be SO harsh on writers who get this equation wrong, who write unlikeable characters–because the writer’s mistake READS as the writer’s failure to differentiate good from evil, which is itself unlikable). The writer has awarded the highest honor–the HEA–to someone who doesn’t embody these values.

So how we feel about consent, and dubcon, and noncon, affects how we feel about whether what the character has done is forgivable/redeemable (and self-awareness plays into this, too–if self-aware, not likely to repeat the mistake; if oblivious, repentence seems more likely to be temporary), and how we feel about whether the character is forgivable/redeemable dictates whether we feel the HEA is deserved, and whether the HEA is deserved determines, to some extent, how we feel about the writer. When you get mad at a writer who doesn’t seem to grasp the subtlety of notions of consent, this is where the problem comes in–the writer isn’t nuanced enough, the character (who represents the author’s perspective because HEA is a stamp of approval) isn’t self-aware enough, etc.

Fascinating … obviously the troublesomeness (or not) of dub-con/non-con is seriously a conversation for other people and far beyond the scope of my original post, which was about issues of normalising and visibility, … but your point about the shooting in LoS really interested in me so I hope you don’t mind if I respond to that?

LoS was one of the first romances I ever read, and remains one of my all-time favourites (although Mr Impossible could probably give it a run for it’s money) and I can remember being basically amused when Jessica shot Dain … because he was being a dick and deserved it. Which, of course, is probably somewhat problematic when you unpack it because, in general, people do not ‘deserve’ to get shot.

The thing is, I’ve read quite a lot of romances since and, historicals in particular, seem to feature shooting the hero as a sort of … joke, almost? Like, stop being a dick, bang, oh wow, you were serious about me being a dick, I guess I should have listened.

I probably don’t have enough context for this but my feeling is that LoS represents a sort of turning point because, in that book especially, the scene seems to echo a similar scene in DEVIL’S CUB, where Mary shoots Vidal, which is absolutely not played for any laughs at all.

I’ve always found that scene deeply powerful, because Mary is so incredibly vulnerable in it. She’s such a calm, collected and generally admirable person and yet the social / physical power disparity between her and Vidal means she is *genuinely* threatened and terrified by him, so much so she feels the only way she can protect herself is to shoot him. And, for me, it’s not really about whether Vidal ‘deserves’ to be shot – simply that the entire context, the power dynamic, and the real potential for rape and violence, is so fucked up that it was only option left for both of them. And obviously it’s kind of an eye-opener for Vidal, not just about Mary, but about himself, and his place in the world compared to hers.

And I feel that there’s something kind of similar going on in LoS even though it’s played slightly more comically in some respects – because Jessica does it quite stylishly and Dain is sort of basically fine. She’s not tired and desperate and lost in quite the same way as Mary, and she’s not quite as personally or sociably vulnerable. However so does it at the culmination of this quite light-hearted power game that’s been going on between them in which they’ve been equally matched and consenting partners. But Dain has one of his freak-outs and basically ruins her, and there’s nothing she can do it about it – something he makes very, very clear when he stomps off, leaving her disheveled in the garden, with her reputation in tatters and his undamaged.

And, again, like the business with Mary and Vidal … it’s sort of when Jessica realises, and the reader realises, that while the power game between them was tantalising and supposedly balanced, it was never balanced, and it could never be balanced, because it took place at Dain’s indulgence. When he feels she’s gone too far, or it’s no longer in his favour, he gets to wreck her life, throw her own helplessness in her face, and bugger off again. And what makes it worse is how completely brilliant Jessica is – strong, honest, brave. And yet that carries no weight against Dain in a tizzy. Just like Mary trapped in a room with Vidal.

Sorry, I’ve just written an essay. I just think it’s really interesting, and really well done, and maybe I’m just far too blithe about dudes getting shot … but it didn’t (in that book) strike me as WTF at all, given the context in which it takes place, and the echoes of Mary and Vidal. I mean, I have read other hero shootings which have worked less well for me – usually when they’re played solely for lulz or it’s sort of meant to be the heroine being cute or feisty. And that can be quite problematic. I mean, if I was being vaguely irritating and somebody shot me, I don’t think I’d be inclined to think well of them for it… but, as you say, life and fiction aren’t the same thing.

I know this awkward because I’m essentially comparing a specific instance of “works for me” against an undefined category of “didn’t work for me” but it seems unhelpfully churlish to point at a particular instance in this case. But when I’ve run across this device, and been troubled by it, it’s usually been because it’s portrayed as somehow inherently empowering to shoot someone. And maybe it is, or it can be, I don’t know. I guess it depends on what they’ve done and your personal morals. But I think what I find powerful about the Mary/Jessica shootings is that they’re both acts of weakness, not acts of strength if that makes sense. Not personal weakness, but social weakness. And you cheer them, not because it’s awesomely cool and sexy to shoot somebody, but because the alternative is intensely real and devastating.

So what I’ve said in a really long way is exactly what Serena said in a short way – it depends how it’s done :) And obviously we’re all entitled to our own WTFs, and I can see why that scene might one of yours. But, for me, the context of it had a big impact on its WTF quotient, and I thought it really worked. But, again, that was just my interpretation, of course.

Hey, that’s a really good take on the LoS shooting and not one I’d heard before or come up with on my own. I haven’t read the Devil’s Cub (which is crazy) but everything you say about that makes sense. I feel like I would have understood it more innately because of the style. Whereas with LoS and it’s humor, I wasn’t really factoring the element of desperation and social injustice, when it’s of course hugely important.

I think also that I’m naturally inclined to be curious about sexual boundaries, and even sexual violence, but am mostly stressed out by shows of pure physical, non-sexual violence. This is a random distinction on my part and the exact opposite of many/most readers, which puts me in a weird place sometimes.

It’s funny that you mention “Devil’s Cub,” Alexis. One of my popular romance classes at DePaul is a historical survey, and it includes both DC and LoS. I’ve always read that scene as specifically alluding to the Heyer–after all, there are a lot of other winks and meta moments throughout the book. So it works for me not only as a scene within the novel itself, but also as a commentary. In fact, I teach it as third in a series: Diana Mayo shoots Sheikh Ahmed in The Sheik, but he’s reloaded her pistol with blanks, so nothing happens; Mary shoots Dominic, but she doesn’t know if the gun is loaded, and she does it after he dares her to (“Shoot then,” he says); finally there’s Jessica, who elaborately and deliberately stages the scene to restore her honor. I miss teaching that class!

Just touching on a couple of points…

I do think these fictional situations give readers *and* writers opportunities to explore difficult things. As Shannon (my real name), I write middle grade and YA, and study that field of lit, and this discussion renews every time book banners get their panties in a twist about drinking or drugs or sex or abuse in a kids’ book. Not only are there kids out there who *are* dealing with those things, a lot of kids exist who want to explore those situations from a safe distance. Maybe they want to think about how they would react. Or act. Or prevent. And that’s OK.

And I appreciate @SerenaBell’s comments about the HEA. I just wanted to add that *knowing* an HEA/HFN is coming at the end of a romance tends to mitigate my reaction to dick behavior in the story (of course, the dick–male or female still has to earn the HEA/HFN). No such promise exists in other genres, especially literary fic, and dick behavior has made me put down more than one of those. The only book I’ve ever thrown across a room was Wally Lamb’s I KNOW THIS MUCH IS TRUE, and it was the behavior with no promise of redemption that did it. Couldn’t finish it. Does that make me a pussy as a reader? Possibly. But that HEA in romance definitely creates a safer emotional space from which to read.

Mia/Shannon, that’s a good point. I am definitely willing to following a character who’s behaving badly to an HEA, whereas if I get a whiff in lit or women’s that there will be no conversion/redemption, I lose patience. But I think in order to be willing to go along for the ride, I have to feel like the author has mastery over the situation–recognizes the nuances of the right/wrong, has enough mastery over the writing of the character to make me believe the character is self-aware and capable of reforming, etc …

Absolutely, Serena. I have to trust that the author understands (and will be informed by) those nuances. And, in line with Elinor’s comments, I appreciate an author who isn’t afraid to present behavior considered normal or expected within its historical or spec-fic context, but which is not acceptable today or in our present environment. Examples: Jamie whipping Claire in OUTLANDER, Meoraq claiming a virgin (and possible minor) as his due in LAST HOUR OF GANN. Basically, I appreciate being reminded that ours isn’t the only society within which people have functioned and made decisions — good ro bad. :)

Amber:

Really thoughtful, and thought-provoking, post. This line gave me a lot to think about:

“And when I read a book with bad behavior, am I exploring it or am I tacitly absolving it?”

I think the answer depends not just on the reader, but the assumption the book asks you to make about the nature of that behavior, and your willingness or unwillingness to accept its assumptions. Does the book present the behavior as bad? Or does it present it as acceptable? If you become the book’s “ideal reader,” in reader-response-speak, then you accept the book’s interpretation of events. Or you can read the book as a “resistant reader,” rejecting the book’s interpretation. You’re doing the latter, I think, when you read older historicals, which (in my view) present dub-con or forced consent not as historically accurate behavior, but overall acceptable behavior that just happens to be taking place in a historical setting.

So boo to those who use “he’s too bad to be hero material” to shut down conversations, and cheers to those like you who invite us to talk about the whys and wherefores.

— Jackie